Old Brey

The Stroller

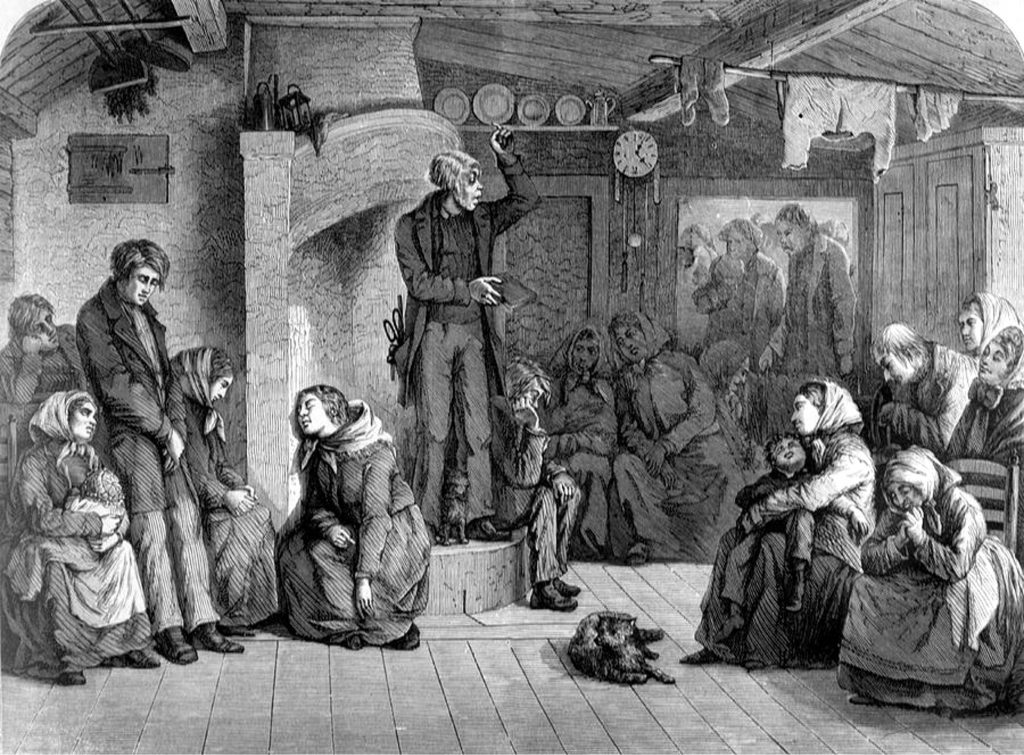

“The Old’ Bray” was a behind-his-back cognomen for the Rev. Joseph Brey, a self-appointed itinerant preacher, who afflicted himself and his slatternly wife on the people of the Kankakee area of Pleasant township some eighty years ago. He was a graduate of the Academy of Accidental Environment. During the Civil War he was popular with the men for his stentorian imitation of a visiting exhorter, but after the war was over and the destitution of reconstruction set in, Joseph Brey somehow found out he could actually take up a collection, after delivering one of his three memorized burlesqued sermons. The small caliber hill folks in the Kentucky mountains didn’t realize he originally tried to amuse them with an army gag—so abruptly Joe Brey became an itinerant preacher.

About eighty years ago Joe and a wife he gathered along the way—and a weary horse and ramshackle buggy—appeared from nowhere and held a series of three meetings in the south part of Pleasant Township in south Porter County, Indiana. Collections were unusually good, and the people generous with dinner invitations, so Joe decided to stay right there. But after the newness had worn off, and the same sermons had been repeated several times the good people of the Kankakee began to wish the couple would stop boarding round and go elsewhere.

“The Old Bray” was consistent in his one main belief that “The Lord will Provide” but finally after the couple had occupied the spare room too long in each of the few homes along the river, the men got together and ‘raised’ a cabin for the preacher and his wife, and furnished with all the unwanted furniture from the several lofts and attics. J. D. Dunn said: “Some unwanted bedding, some unwanted furniture, an unwanted preacher and his unwanted wife, were ceremoniously installed in a 12×16 raw-hide cabin–and a load was taken from the backs of the people of the community”

Rev. Brey wasn’t too bad as a class leader, and as an emergency preacher he could bury the dead with sufficient ceremony or raise a hymn at any gathering. He could say a prayer’ when called upon, so he was tolerated. Mrs. Brey tended a rambling garden and sometimes traded ‘garden sass’ at the island store. Kindly neighbors held a donation party twice a year, even though Joe could never be persuaded to be an emergency field hand. He had a perpetual ‘mizzery’ in his back that kept him stretched out on a barrel-stave hammock on his ‘stoop’, as long as the weather permitted. The neighboring housewives sent over a loaf of bread or a pot of beans once in a while, even though Brey and his wife were just naturally lazy. During the days before an election Joe was apt to receive a few ‘store bough tent garments and a hat and shoes, and his wife go a wrapper or a sun bonnet or even a pair of shoes also. He may have been “The Old Bray” to the neighborhood but he had a vote. He accepted everything with the same comment: “The Lord Loveth a Cheerful Giver” and he voted against the candidate who gave him the least. He was something of a genius and a combination of laziness and pride, a blending of an adopted religious fervor and an inner wonderment—wondering if he could by chance be actually doing some good. The neighboring men said: “Old Bray is too lazy to work and too scared to steal” He was a little man with a big voice. Hellfire and brimstone was his stock in trade. His vocabulary was as rustic as his scraggly chin whiskers. He had three long-winded sermons learned long ago, which he called. “Cast your Bread upon the Waters”, and “The Lord Loveth a Cheerful Giver”, and “It is more Blessed to Give than to Receive.” He added just enough to each sermon to include the title he gave them—but primarily he stuck to the memorized text.

“That old log cabin was the Brey’s home for several years. By now it has fallen into ruins, or has been carried off log by log, or sash by sash. The door, which had been donated in 1876 by Earl Hall finally appeared on John Card’s cabin,” said the Old Settler, in 1912, for the Lewis History, and he continued: “I saw it a few years ago, in 1906 I think—a few years! Gosh Almighty that’s thirty years ago. And when I saw it, it was a windowless, sway-backed ruin, a wonderful place for marauding ghosts. J. W. Felton and Tom Wood swore there were ghosts there—and I know even the chipmunks and the pack-rats had deserted it long ago”

Bill Cain said: “There’s a set of ground-hog burrows under the floor, and that’s about the only sign of life ever seen about the place since “The Old Bray and his woman departed long ago.”

°It’s my job” continued the Old Settler, “To tell how the Brey family finally departed, not about the once-time members of his ‘congregation’, but I must remark that Jim Purdy and Pete Williamson and ‘Mike’ Molihan were glad to see the couple go, for these three families practically kept the old goat alive during his last years along the river. Somehow the old codger overheard Mose Golliher call him “The Old Bray”, and that hurt his pride. He traded his furniture to Sam Taylor for a gaunt old mare, to replace the horse that had long since died. He soaked the buggy wheels in the river several days, put in a few; new tire bolts and otherwise repaired the buggy, and started for Kentucky.

I have copied from the newspapers that last sermon, at the grave of old William Billings: “Today we are burying this old man with no descendant nor family to mourn his death. There’s nobody left. Once the Billings family was predominant in Pleasant township. William and Ernest and their wives and children came in 1836. For almost half a century they suffered the hardships of the pioneers, at first, they all lived in a windowless lag cabin, and they grew and prospered until each family consisted of three children and their parents.

Then came 1849 when the grim reaper came on the wings of the miasma. Year by year he came until the whole township was sorely depleted, and the Billings families were reduced from ten to eight, then to seven and to six, and then to five—and then came the Civil War when two of the boys died on the field of battle in Georgia—then there was but three. Ernest died in 1870. William outlived his son Junior by 12 years—and then there was only old Bill left. Today he lies in this crude coffin. There’s nobody left. Not a relative to miss the old man, who at eighty was lonesome and ready to go. These few friends and neighbors, hardly a dozen in number are all that remember the 160 acre tract that was once a water-covered prairie fringed with trees, which old Bill reclaimed and farmed all these years—today it belongs to the money-lender who saw old Bill through his unproductive and declining years. The fact that the moneylender gets a highly valuable farm for about a quarter its worth needs not concern us—he lent Old Bill enough to live on—and he needed nothing more. Ashes to ashes and dust—lower the coffin and cover him up—and to all of you my wife and I bid a fond farewell”

“The Old Bray” and the gaunt grey-haired woman climbed into the buggy and headed back to Kentucky.