RECLUSE AND SAGE

Charles Withrow Leaves the World for the Kankakee

HIS HOME ON AN ISLAND.

Family Made to Share His Loneliness and All Are Content.

LORD OF A LITTLE REALM

Chicago Tribune

Kankakee, Ill., Nov 21, 1898

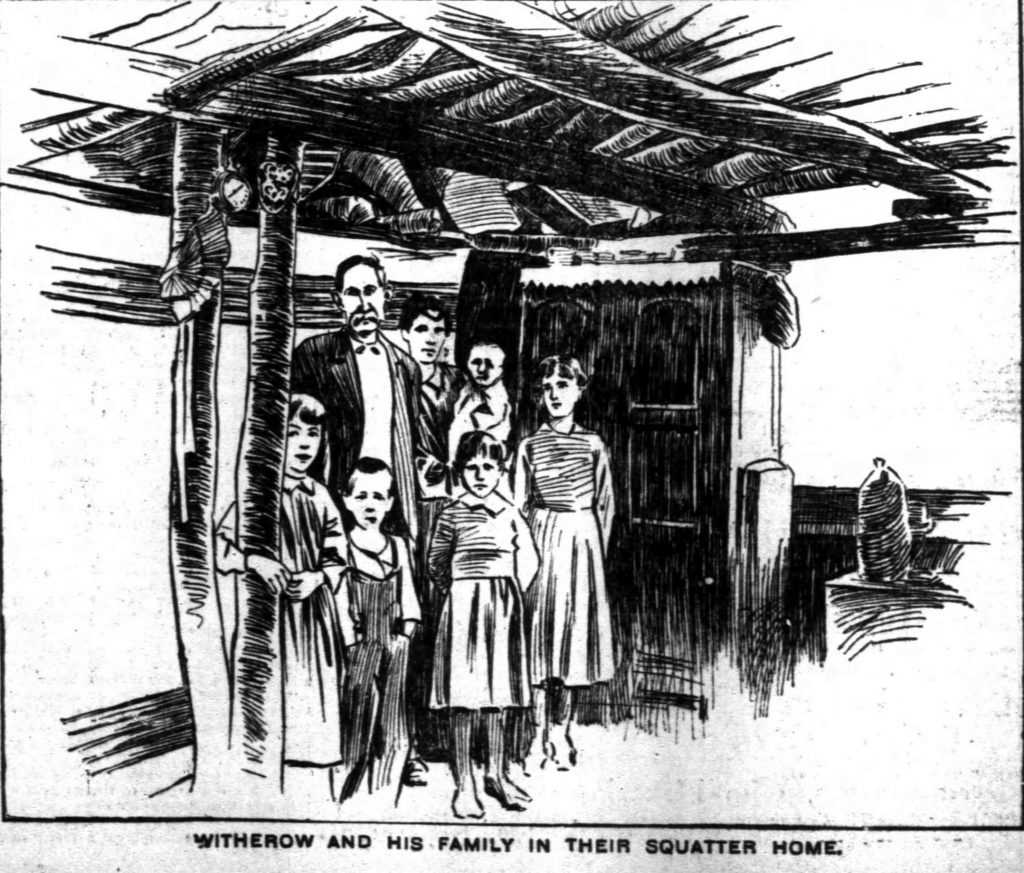

Dissatisfied with civilized Institutions, distrustful of mankind, and desirous of returning to a primitive existence, Charles B. Withrow one year ago isolated himself and family from the rest of the world. There is an island In the Kankakee River within easy rowing distance from this city. It is perhaps a quarter of a mile long and 1,200 feet across at its widest paint. On this island the eccentric Mr. Withrow had established himself. Here, in a rambling series of huts that would he disdained by many a self-respecting savage, he makes his home, andd, with his family, is happy and contended.

The Island is one of the most picturesque the classic stream affords. Indeed, it is more picturesque than comfortable or healthy, for the mosquitoes are large and voracious, and the pathologist of the Kankakee Insane Hospital, who camped on it one summer, and combined business and pleasure by engaging in various scientific experiments, discovered seventeen distinct specimens of bacteria, all of the healthy and industrious variety. But nature has been kind to the island home of Withrow. Lofty trees rear their heads above the dense undergrowth. Creeping vines connect the branches and the lower verdure, forming here and there arbors of rare beauty.

Withrow a Character

But it is doubtful If Withrow gives much heed to the picturesque character of his surroundings. He goes in for cabbages rather than sentiment. He is more-interested in his corn crop than scenery, for the old man and his family must live somehow and have reduced a portion, of the virgin soil to cultivation.

Withrow is the queerest character imaginable—a man of 67 years, with weather beaten countenance, piercing eyes, and hawkish, nose. His clothing and the rubber boots he is rarely seen without would indicate sewer builder. HIs conversation is that of a refined and educated, gentleman. It is supposed, from his knowledge of books, his mathematical and scientific skill, as well as his philosophical precepts, that he is a university man, but he speaks of his past with reluctance. A socialist in politics, he does not bore one with a discussion of his principles.

Withrow has an interesting history. He originally came from Indiana and has been in various institutions for the mentally afflicted. Six years ago be was an Inmate of the Kankakee Insane Hospital. His mental aberration is the result of wounds received in the service of his country during the civil war. Withrow had not been in this institution long when he was paroled. His case was a puzzler. Members of the medical staff were agreed that he was not exactly sane and not exactly insane. At any rate he is entirely harmless, although his unique fancies at times snake him something of a nuisance.

Withrow has a wife—not his equal in the matter of education, and nine children, the youngest a baby born on the island a few months ago and named “Islet” in commemoration of her birthplace.

When Withrow was released from the hospital he started an employment agency that was to have accomplished great things. Mr. Withrow’s expectations might have been realized if people could have overcome their habit of looking askance at most of his projects. The employment agency to some extent partook of the character of a communistic colony. Everything went into the common fund. It might have worked well enough if some of the members hadn’t succeeded in “doing” the rest. So the Colony became a bursted bubble and Withrow engaged in sewer building and other work in which his engineering knowledge stood him ingood stead. He made money, but the bee that kept buzzing in his bonnet interfered with the success that otherwise would have rewarded his efforts.

A couple of years ago Mr. Withrow secured $700 back pension. When he left the hospital, a conservator had been appointed to look after his money. The conservator grabbed the $700 to the great disgust of Withrow, who had planned numerous ways of placing it in circulation. The difficulty in securing this money and the quarterly installments that subsequently came from the government explains in part Withrow’s deep disgust with mankind and his conservator in particular. He was making his home at this time in Waldron, a village on the Kankakee not far from this city and about the same distance from the island as Kankakee.

The good people of Waldron soured on Withrow and used their endeavors to have him returned to the hospital. Withrow tangled up a jury at his trial and defended his so bravely no one could say with certainty he was tint in his right mind. If he was wrong in his head he still was so much better informed than the average man that the Judge did not feel like committing him to the insane asylum. it was decided to let Withrow alone, but his conservator was not discharged.

Driven to the Woods

Completely out of sorts with Waldron and Kankakee people, vexed beyond measure with his conservator and the County Judge. Withrow became something of a latter-day Robinson Crusoe, with the difference that his seclusion is voluntary, and he took with him his family—the members of which appear to believe in him implicitly.

Hamlet Island—or, as it is called by common consent, in honor of its odd inhabitants, Withrow Island—is not less interesting than the recluse.

The first thing that attracts attention is the long channel leading from the east shore to the remarkable habitation of Mr. Withrow and his family—a dwelling partaking of the characteristics of a Kansas dugout, an Esquimo igloo, and a Sioux wickiup.

This channel is the result of the indefatigable labor of a single pair of hands. In fact, Withrow’s house and all work accomplished on the island—and some of it may be regarded as stupendous—was performed by the islander. He is another GiIette only instead of a “toiler of the sea” he is a toiler of the river. The channel referred to leads to the front door of the Hamlet Auditorium, as Mr. Withrow is pleased to term his domicile. In it he keeps boat, a wretched tub that does not look worthy. “Not a good boat, Mr. Withrow,” you say “It’s the best I could secure for the $3 allowed me by my conservator, and I had hard work to get that”

Nearby is the keel of a much larger craft the old man started some time ago,-but was compelled to abandon for lack of suitable timber and funds. He speaks of it regretfully.

Withrow’s house may be called a series of dugouts—a veritable Robinson Crusoe’s cave—kept in good order. When the misanthrope decided last November to isolate him and family from the rest of the world, he had nothing but an old tent for shelter against winter’s chilly blasts. Like a mole began to dig. Before winter had far advanced he was fairly comfortable. A cookstove ad a baseburner made the atmosphere of his house reasonably warm.

“But this is nothing like what it was last year,” the old gentleman, with pardonable pride, as he politely shows his guests about.

When Withrow began to construct his “auditorium,” in earnest he made a hole forty-five feet long—a estimation of the channel before mentioned and extending in the same direction. It is its intention to ultimately lower this so the boat may be run into the !louse. In its present state the hall floor is covered with water when the river is at its height. .

Connecting with this hall are several apartments, each twenty-four feet square. One is the kitchen and dining-room. Mr. Withrow confidently informs the visitor this will seat sixty-four people. “You see,” said he, “it is my ultimate intention to convert this into a place for business. This will be the restaurant. Other enterprises will be located in adjoining apartments.”

Connected with the kitchen are sleeping apartments, which may be further partitioned by curtains. Other rooms are need for storage and a variety of purposes.

The house is a half and half arrangement—half dugout and half cabin. The outer walls are banked with earth and the roof, which is thoroughly braced by natural timbers, is likewise protected from the cold. Where the walls are not so protected canvas has been hung. Raised at intervals it affords a chance to air the dwelling.

Some idea of the extent of the rambling structure may be gathered from the fact that more than 150 stout timbers have been utilized as roof supports.

Like the shrewd showman he is, Withrow keeps up a running conversation, acquainting visitors with his odd theories and fancies. It so happened that one of a recent party that visited the island was a physician who had recommended Mr. Withrow’s commitment to the insane hospital. The islander is not the least resentful, and was glad to welcome the medical man, but could not resist the temptation to loose a few satirical jests of which his insanity was the subject. Placing his hand upon a particularly crooked roof support, he remarked “Society has many such crooked sticks, yet with’ proper care all may be utilized”

On the roof of the dugout there is a tent. This is where Withrow. and his wife, and nine children, including little ” Islet,” sleep at the present tune. When it is cold they will go below. Withrow’s eldest child is a 16-year-old boy. “Don’t you find when the river Is partly frozen so as to make boating and walking on the ice alike impracticable that you are kept here longer than is convenient'” Inquired the physician. “Some might find trouble in reaching shore,” responded Withrow.” but.” extending his arms. “I don’t find any as long as I possess these two arms. Last winter my children r missed few school days.”

Those of Withrow’s children who are of school age are instructed in Waldron. Withrow supports himself and family upon his $12 a month pension, eked out with the few vegetables he raises, fishing, and an occasional sale of wood, cut on the island. He finds it hard to make both ends meet when his eldest boys can get nothing to do. Yet, except for occasional set-tos with his conservator. Diogenes in his tub were no more contented a philosopher. It must by no means be accepted as a fact that Withrow is permitted the’ undisturbed possession of his domain. A wealthy Chicago woman, whose stock farm is located opposite the island, claims the place by virtue of its proximity to her land and many years’ undisputed ownership, although she has never occupied the Island or used it for any purpose. But she doesn’t like to have Withrow and his family around and has unsuccessfully tried to oust him by legal procedure. A case now pending In the Circuit Court is expected to settle the question of ownership some time or other. Meanwhile Withrow doesn’t seem to worry. He claims to have government authority to occupy the island, and displays a map he secured from the Department of the Interior that shown how the Island vicinity looked in the early days of the Prairie State, when Indians had their wigwams in the vicinity of Kankakee and Bourbonnais. According to Mr. Withrow—and lawyers have said his position is not a mistaken one—the island, with others in the Kankakee, was originally the property of an Indian Princess with a musical, hyphenated, and unpronounceable name, and upon her death they reverted to the government: also that the river is navigable. Consequently, he has a right to establish title to the property by virtue of the preemption act, provisions of which he has been careful to observe.

Withrow’s schemes would fill a book and prove not uninteresting reading. Just now he is engaged upon experiments with an adobe brick. He claims there is enough clay, of the proper sort on the island to makes him a wealthy man: lie is also occupied with a plan for a cooperative commercial agency.

Charles Bell Withrow passed away on October 20, 1899