The Kankakee

Chronicle of an Indiana River and Its Fabled Marshes.

By Fay Folsom Nichols

CHAPTER XVII

Crossings and Bridges

“I like rivers better than oceans, for we see both sides,” wrote Edward Arlington Robinson in “Roman Bartholow.”

Most people, however, like to do more than look. There is a determination to get on the other side.

It is quite likely that the first fellow to cross a stream other than by swimming or paddling, braced a log from bank to bank and teetered across on it. That little trick may have worked satisfactorily on the upper part of our River, but as the stream widened, more than one log became necessary, so they were pegged together and the result was a bridge.

This was all very well, and with a few ferries supplementing the log, things went on in this nice easy manner for some time. But it was risky business attempting to take a cow or a pig over on the log route, and a trifle expensive moving them by ferry.

For instance, posted at the old Sherwood ferry were the general prices: “footman, 614 cents; man and horse, 121 cents; horse and Dearborn wagon, 25 cents; two horses and wagon, 37V2 cents; four horses and wagon, 50 cents; two yoke oxen and wagon 371/2 cents; any higher number animals to wagon, 50 cents; each hog, 3 cents; each sheep, 3 cents.”

When the water was high and the ferry had to run in farther, three times the rate was charged. No person was charged with ferriage who was crossing with his team and paid the regular rate for them.

This particular ferry had been run for some time without the county benefiting by a license fee, so in March of 1837 it was put up for bids, with Joseph Stearns and John Scipp granted a license for $9.

Of course, farther down the river, near the limestone hog-back, fording the stream was the thing. Fords, at that, were few and far between. But civilization has a way of increasing its demands. Bridges has been one of them.

Any story of bridges now spanning the river is not only the story of the settlement of the people along its banks, but the need for trade and communications of an expanding nation. Chicago was the great objective of the frontiersmen coming up from the lower Wabash region and the Ohio Valley. Then, as now, all main highways leading from the south, southeast and southwest across Indiana and eastern Illinois had to cross the Kankakee to reach that city and, in present times, the noted Calumet industrial area.

Oliver H. Smith, an early circuit lawyer of Indiana, stated in his memoirs that when he entered the State in 1817, there wasn’t a bridge in the state. But the Kankakee at that time was still in the hands of the Potawatomi, and such a little thing as getting from one side to another didn’t worry them.

“So far as any access to it from the prairies is concerned,” wrote Timothy Ball, early Lake county historian, “it is like a fabulous river, or one of which we take on trust. The blue line of trees marking its course can be discerned from the prairie heights; but only occasionally, in mid-winter or in times of great drought, can one come near its water channel.”

Beds of muck, interspersed by sand ridges, was nature’s problem imposed upon man. And, resourceful fellow that he is, man turned to the “blue line of trees,” for available supplies for his bridge building.

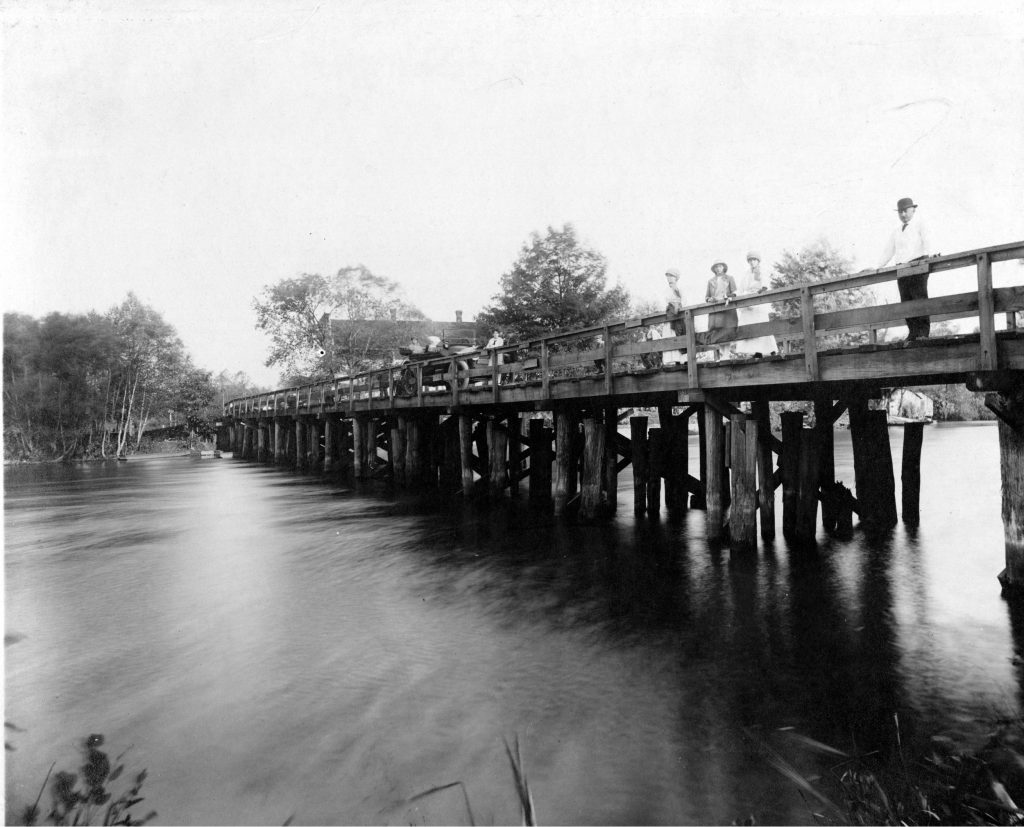

Structures were roughly but soundly built by driving piers of piling so placed as to support spans of framed timber. These were covered with floor planks sawed from trees of larger growth than the piling supporting the structures.

Convenience and experience in the lasting qualities of material for use under the impact of the steel shod hoofs of horses, and the tramp of cattle over these bridges demanded

the best. And that best meant the choicest of white and burr oak were cut, sawed and framed into those structures.

There was nothing about those early bridges that might cause admiration, so far as their appearance was concerned, and the engineering problems taken to place them where most needed, were very simple. The skill required in their construction was negligible, though Bonnie Bordman made a name for himself, hewing, scoring and framing the great timbers.

The first bridge over the River in line with the old Chicago-Vincennes trail was built about 1842, and Bonnie was given the job. On the day of the “great raisin'” neighborhood men gathered to give Bonnie a lift, and the old Hill tavern which was located on the south side of the River at the crossing, treated to whiskey.

The contractor for early bridges, or road supervisors who had to keep them in repair, usually planned to do the work when the stream was under a heavy coating of ice. This facilitated his operations. If he could possibly wait, winter was his best friend and most accommodating workman.

These wood-pile bridges served for all the needs of the traveling public during the time they were in use, and they had one very commendable virtue-they were easy on the taxpayer’s budget.

To encourage road building, in 1802 the government granted 400 acres of land to any person, or persons, who would “Open up good roads and establish houses of entertainment thereon for five years.” By 1835 Congress was granting a three percent fund for the building of roads and bridges. Porter county was much interested in having a bridge across the River at Eton’s Ferry (Baum’s Bridge) and asked for some of the money. Thomas Randle of jasper county had been appointed agent for the distribution of this fund, and refused to draw any for the proposed bridge.

But the powers that be accordingly dispatched Randle, and Joseph Scipp moved across from Porter into jasper to succeed him. Construction began in 1837, but after the log piers had been built and stringers placed for a complete structure three quarters of a mile long, everything was swept away by fire. Subsequently a bridge over 700 feet long was completed at the location, jasper county constructing a long and substantial grade at the southern end.

The building of bridges necessary to cross streams became county financed projects. Ownership and upkeep, up to the time of the creation of the Indiana State Highway Commission, was vested in the county where the bridge was located, and was usually built from taxes set aside for that purpose.

Another ownership was set up for the purpose of building a bridge where it was to cross on the boundary line formed by the River. The funds set aside could be raised by taxation in each of the bordering counties, or by Bridge Bond issues. The amounts set aside for joint bridges were pro-rated according to assessible valuation of the adjoining counties.

Since the River, as was mentioned in the beginning of the story, forms wholly, or in part, the boundary between seven Indiana counties, the twenty bridges spanning the Indiana end were built and jointly owned by funds from those counties they connected. There is one such bridge jointly owned by three counties. This is the bridge known as the Range Line Bridge which crosses the River south of Jerry’s Island on the Range Line road. Jasper, Lake and Newton counties built the structure in 1927.

When the State Legislature organized the State Highway Commission in 1918, that department was given the right to raise funds by general taxation for the purpose of acquiring title to all bridges located on, or that might be built, on all State highways.

Since this department has been created, there have been constructed on State roads crossing the River from South Bend to the Indiana State Line, seven new bridges of standard construction. This, of course, means that each bridge is of sufficient width of roadway and strong enough to carry modern traffic.

In the bridge building program many peculiar situations have presented themselves. One was the bridge without approaches. About forty years ago a small bridge was erected across the river on the road now designated as State Road 8. On the far side of the water there apparently was a “trade-at-home” slogan set up, and with political intrigue taking a hand in the matter, it was eight years before an approach to the bridge on that side was built and the bridge put into use. All of which prevented the road being open to through traffic. Now, with the State Highway taking over, such complications are out of the picture.

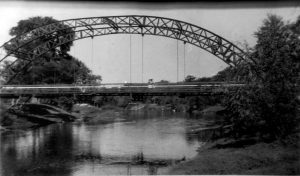

Another was the building of Dunn’s bridge. It was the first iron bridge built on the upper end of the River, and was fashioned from iron salvaged from the dome of the Administration building of the World’s Columbian Exposition-The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

P. E. Lane, a Boston engineer, conceived the idea of salvaging the iron from the domes and roofs of the great buildings which were of fabricated iron. He versioned this material going into bridges at low cost, and so it happened that during the next few years after the fair closed, the streams and rivers of Northern Indiana, particularly Lake and Porter counties, and that part of Illinois nearest Chicago, were furnished with bridge material whose first purpose had been to shelter exhibits from all over the world. There are many of these structures still in use today.

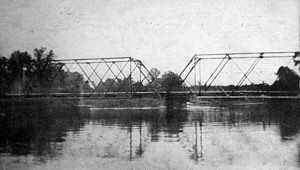

Some of the steel in the bridge on State Road 55 which connects Shelby and Water Valley has been moved four times -all of it twice. The framework, originally consisting of four spans, each one hundred and fifty feet long, was built in 1914. After the dredges went through, the bridge had to be reset, so two spans were set side by side. Now north and south bound traffic use separate bridges.

When this first steel bridge, an old high truss type, was built, Lake and Newton counties which it connects, shared expenses. Lake county having a larger assessed valuation, paid more than ninety percent of the entire cost. At that time the county line was located under the south span of the bridge.

Later, with the straightening of the river, the county line was changed to the new channel. This moved the line under the north span, thus leaving three of the four spans wholly within Newton county. So, regardless of the fact that Lake county had financed ninety percent of the building cost, Newton became the sole owner of these spans. She took two of them and located them across the Iroquois River.

Then Newton joined again with Lake to put the remaining span beside the one already in place over the new channel. Again Lake county paid more than ninety percent of the cost.

The road designated as the “Old Grade” was built in 1894. The dirt for the grade was thrown up with a floating dredging machine, and here was created a road that brought the towns of DeMotte in jasper county, and Hebron, in Porter county, closer. Before this, travelers either crossed at Shelby or Baum’s Bridge. This was a narrow, treacherous road at the best, and in summer with willows and marsh brush growing high on either side, one not familiar with the road could easily drive into the ditches that bordered it. Drivers meeting, one of them would pull his team and wagon out as far as he dared and stop, while the other driver proceeded on his uneasy way. But a poor road was better than none, and it was one more way to reach the river.

The present Hebron-DeMotte connection-State Highway 53-was the first direct road between the two villages. It opened up another road for down state travel, a need which had been long felt. With the area first cleared of the timber, the road was thrown up in 1907 as parallel ditches were cut riverward.

This new road formed a barrier for the annual flood waters on their way to the Illinois River and the Mississippi. Gaps had to be made to allow this water to get away. These gaps were called spillways, of which there were three in Porter county. Each one had to be bridged, requiring six spans in all. These were of steel construction of the low truss type. Jasper county took care of this condition with bridges of wood pile and timber construction.

About ten years later the new channel was constructed and the overflow bridges were of no further use, so they were removed to other sites. Two of these spans were placed over the new channel on the “Old Grade” and are still in use. Now jasper county keeps the south span in repair and Porter county does likewise with the north one.

When this first steel bridge went up in 1910 it was, at the time of its erection, the last word in bridge building. Of course, the surrounding land was covered with water, and the great timbers and steel which were to go into its framework were taken in during the winter months over the ice. When the work began, horses used on the job were ferried there in great scows that also moved sand and other supplies.

The two bridge spans were each one hundred and thirtyseven feet in length. The width was fifteen feet, nine inches, and the floor was of heavy oak planking.

At a state banquet held shortly after the completion of this bridge, Professor Hat of Purdue University, then considered the greatest authority on engineering in the State of Indiana, was asked how long the bridge would last. He replied that with proper care, it should last five hundred years.

It wasn’t that the river widened or deepened that defaulted the engineer’s statement. He just couldn’t foresee the rapid change in traffic with the great strain of trucks and busses of an automotive age.

On November 5, 1934, detour signs were removed at the Kankakee River bridge on State Highway 53, and traffic started over a new $50,000 bridge. A camel-back type of truss bridge, resting on round column piers and void of abutments and retaining wall, it was the first of this design to be used in Indiana. There was a thirty-two foot approach at either end, and all exposed concrete work had been polished to give the effect of marble.

The bridge which replaced the one built in 1910 that was to “last five hundred years” had been financed by the Indiana State Highway Commission. In accordance with the labor code at that time, the thirty-nine men employed on the project worked NRA hours. The job being on county lines, it required the use of men from the three counties Jasper, Porter and Lake.

A greater menace than fire to the old wooden bridges were the spring ice jams. If the country had suffered a particularly long, hard winter, and March thaws came on suddenly, let the wooden structures beware. Any number of them could count on being torn bodily from their moorings by the gorge, and carried down stream. Towns, especially those of Momence and Kankakee City, were usually flooded as the water rose with the movements of the gorge.

“March!” warned the Momence Reporter in its first issue of the month in 1833. “Spring has come, but the river has been higher than the thermometer this week.”

By the next week the editor was writing, “The ice has not passed Henry Moe’s place yet,” in that better-watch-out tone. If the 1,039 inhabitants weren’t on the alert, it surely hadn’t been his fault. He had been more or less apprehensive since the preceding November when the thermometer had dropped to six below zero and the river had “froze over as far down as Mrs. Heeter’s.” Let winter start in early and keep it up, then watch out for ice jams in the spring.

The second week the news was a bit upsetting. The Aroma (Waldron) wagon bridge had been carried away by the ice the Saturday night before and lay in the water just below where it had stood. The railroad bridge was reported to have moved two feet on some of its piers.

On the Wednesday preceding, the village authorities had become alarmed and had made an effort to loosen the ice above the south bridge. However, there wasn’t much they could do. A little after noon, all the ice-about twenty rods long, and extending from the south bank to the islandgot a savage punch from the upstream gorge that had been “lying in wait near Metcalf’s.”

This great chunk has threatened the town since February 17, and people were getting more or less jittery. Then the entire mass began moving. Great thundering and cracking, groaning and scrapings brought in people from miles around to stand in awe at the immensity of the gorge.

Men and boys ran along the banks with poles shoving and pushing, yelling and cursing. The yelling and cursing did as much good as the pushing. In spite of the prayers of the righteous, nature played the winning card. The entire mass came down to, and partly through, the wagon bridge as far as it could.

There was a mile and a half of the smooth shining monster, extending the full width of the stream. The water came up and made good boating through the business district of the town.

Further effort was made to dislodge the ice. It moved again, then gorged. This time the water spread over all the land along the river. In some houses it rose to a depth of two feet.

The knocking out of one bend left a forty foot space, but the weekly sheet assured everyone it was “perfectly safe except for droves of cattle,” since President Kenaga had taken personal supervision to its repairing and forty foot stringers and a truss were supporting it. By May everyone had forgotten their March troubles in the launching of the Starry Queen, and the Reporter was off to a new story.

“The new steamer that is to ply like a profane swearer, from dam to dam, on the briny Kankakee, was launched a week ago Saturday. She is 741/2 ft. long, 12 ft. high, has a 50 H.P. engine and will carry 300 passengers. Her work day business will be to tow sand barges from the Iroquois River to the Asylum, and her Sunday and holiday work to carry excursionists.”

Probably there was a divergence of opinions when it came to erecting the first iron bridge. Taxpayers, no doubt, howled, and local politicians used the issue as a platform, since there was still a plentiful supply of hardwood when the new and untried material was placed on the site.

To Illinois, however, goes the credit for launching out on this wild venture. The Kankakee Gazette, published in its issue of June 7, 1883, “Wilmington has let the contract for an iron bridge over the Kankakee River at that place, for $17,421. The bridge is to be completed within 90 days.”