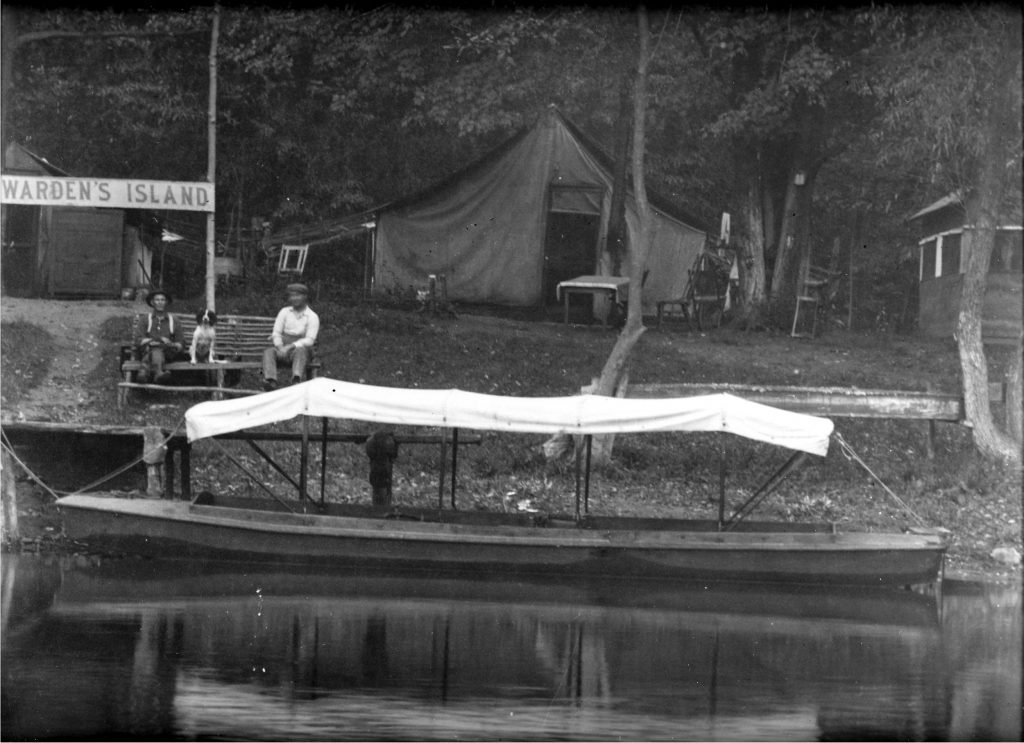

WARDEN’S ISLAND, ON THE KANKAKEE, RETREAT FOR INDIANA WILDLIFE, THE CENTER OF A CONSERVATION CAMPAIGN BY COMMISSIONER MILES

The Indianapolis News

September 18, 1913

by Walter Greenough

Warden’s Island on the Kankakee, September 13. Down from the black sand of this little knoll flows a lonesome, silent stream. It is the mystery river of Indiana.

Hare it’s a snug little “pioneer” camp, surrounded for miles by swampy woods site George W. Miles, state commissioner of fisheries and game, and about him are half a dozen brawny sons of the wilderness. They are Miles’s deputies.

On the far side of the silent river there is a small bayou—one of thousands along the stream. As the sun first shot Its golden bars across the reflected shadows of the water birches and the elms down by the low bank in front of the island here in the morning, a big fish leaped out of than chilly water and back again with a heavy splash. There was a scurry of minnows among the lily pads there in the bayou. The long-necked sandhill crane that sat silent as the brown cattails about him jerked out his long neck and daggerlike beak In the direction of the commotion.

From the depths of the of the lily pads came a muffled croaking of a dawn-dreaming bull frog. Among the water birches gleamed a blood-red spear of sage. Down the stream a hundred yards there was a cluster of vary-colored wild hollyhocks that fill hundreds of square feet of water with the ever-changing color’s in reflection. On the sand bank up the river stalked innumerable blue and green herons and among them a jet-black crow or two.

Dreams a Dream

A mournful toot awl, just getting to bed after his night of prey pursuit mumbled out his weird call from a secure retreat in the marsh behind the camp. Birds of innumerable species sang their matins across the little cleared space here that marks the only habitation of man for miles about. Three lean bird dogs chased a flying squirrel playfully to its home in a rotten log. Then they back for the approval of their masters.

The sun sent its shadows a t a little deeper angle. Two fast flying wood ducks scurried down the river past the patrol launch at the dock. A flock of “squawks”—funny, big birds that no one seems to be able to classify up here—gave a raucous chord and then circled the clearing as the trio of bird dogs barked their derision. The Paradise of the Kankakee had had awaken to a perfect September morn.

It is here—in this Garden of Eden for Indiana’s wild life—that George Miles has dreamed a dream that may come true.

Lively Comment Expected

The idea will stir up more comment—bitterly adverse and pugnaciously friendly—throughout northern Indiana than anything thing that has come to the surface here since Hoosiers skimmed down the river in their little brown “pushboats” and dwelt on its floating banks. The Idea comprehends the dedication of the of the wild stretches of the Kankakee forever to the state of Indiana and to the pleasure of the state’s people.

Utilitarianism—the purely sordid sort—has grasped the ig, silent stream at its northern and above English Lake already, and today there are keen regrets and a big ugly ditch, beginning miles above this beauty spot, and running for miles into the northern counties of the state where two centuries ago LaSalle and his couriers du bois communed with their God of Discovery and found that her was a wonder spirit.

Today the big business men of Indiana, who spent dollars and effort to build “vacation” homes in the wilderness of the Kankakee’s upper stretches curse the giant dredge that turned the duck marshes into overflowing corn fields and left the river an unsightly gutter. Some of the corn grows up there, but the wood duck and the sand hill crane and the king rail and the mink and the muskrat come no more as of old.

Strict Supervision

And because of this experiment—which many say has failed utterly in a region for more propitious to the saving of the marshes than is the southern portion of the stream—Miles has dreamed his dream of the saving of the southern sixty miles of the Kankakee in Indiana to the birds and beasts and nature lovers of the state.

His scheme includes purchases by the state of many square miles in the Kankakee marshes and the establishment of the strictest sort of state supervision over the wild life here. New York, Pennsylvania and other states have done the same thing successfully.

The Kankakee rises pear South Bend. Its source is a channel through which the St. Joseph river formerly flowed. From the northwestern part of St. Joseph county it flows In a southwesterly direction. forming the boundary between LaPorte and Starke counties. Thence it flows west dividing Porter and Lake counties on the north from Jasper and Newton counties on the south. This Island ties on the boundary of Porter and Jasper counties. Then the river leaves Indiana and finally flows into the Illinois river. Its course In Indiana to nearly one hundred miles long. The rate of descent as it flows through Indiana is approximately one foot to the mile. Because of the great breadth of the stream and Its marshes and its consequent shallowness, there In rarely a strong current.

Site for Camp

Out in front of this “pioneer” Camp. where once “Shanty Island” harbored “pirates” and some few decent fishermen, one now almost expects to see a silent Iroquois glide past the willows In his birch canoe with his fish spear poised to strike the gleaming bass or slimy pickerel as they splash to the shore weeds at dawn.

It was this spot, the only accessible high around for miles through the swamps, that Miles chose for the rendezvous of his guardians of the Kankakee. The activities that center about this island of black sand today are known to but few Indianans. The Island is, roughly, about six miles south of Hebron, Ind.

The name was changed to Warden’s island after Miles and his men had found they could use it as a base for their yearlong attacks on the “pirates” of river and land that slowly are giving way In the big marshes about here. There are no nets in the river now and few market hunters in the marshes.

There Is a well-established camp here. Its purpose is not alone the preservation of the wild life In the marshes. The brawny men who labor here guard the wide prairies in Jasper, Porter, Newton, Starke, White, Tippecanoe, LaPorte and other northern counties. In these counties the state of Indiana has a wildlife resource that is not known to the residents of the central and southern, counties.

Underestimated thousands of prairie chickens are in these prairies and Miles has established a, patrol of the prairies second only in importance to his patrol of the river and its marshes. He believes there are 100,000 prairie chickens in this little group of counties, and some of his men, who spend days scouting the prairies on motorcycles, say that estimate is far too conservative. The motor Cyclemen use this camp as their base of supplies. The chug-chug these strange “game cops” has driven the chicken poachers from their former business.

Under a five-year “closed season” which the legislature left in effect until 1915 and which probably will be extended, the `’chickens” that once were the prize shooting birds of Indiana. and neighboring states, have been “cultivated in Indiana again with the most religious care.

Credit to Farmer

This repopulating of the prairies has had the sanction and the co-operation of the Indiana farmer, and to him practically all of the credit for the condition of the ”chicken” crop in Indiana is given by the commissioner. It is Miles’s intention to repopulate the state with these birds. Without the farmer’s aid, the attempt of the state fish and game department to rear the birds again and make them a factor in the game life of the state would have been an utter failure, Miles says. The auto loads of chicken shooters do not come here as they formerly did. The farmer and the “bikecop” have sounded the death: knell of market hunting on the prairies.

There is another part of the protection of the state’s wild life that ls, best exemplified here in the Kankakee marshes. Here each year trappers take from the marshlands at least twenty-five thousand dollars worth of the finest furs. That such an industry exists in the state’s mystery land is practically unknown.

With the aid of the Powers’ “skunk law,” the sturdy men of the wilderness up here are seeing that “fur” hogs do not depopulate the marshes. At night the eerie cry of the coyote is not unusual now. Though Hoosiers who go to Atlantic City for their summer outings. Probably would scoff at the idea of wolves yet remaining in Indiana in any number. Sometimes they are caught. Miles would leave them unmolested in his big game preserve.

The foxes help make tip the pelt trophies of ‘the trappers. Several kinds are caught during the winter trapping season. Chief in the fur industry is the muskrat. His rough houses of branches and rushes, grouped into villages that surprise the layman, dot the marshes in many places. Then there are the mink, the raccoon, the opossum, an otter or two and many lesser fur bearers.

The game wardens see to it that trappers keep their “strings” of traps safely away from the fur trails between April and November.

The river is beautiful for its bayous, its swift turns, unexpected vistas and the mysteries of its low banks.

A journey of four miles, “as the crow flies,” across the marshes, stretches into twenty-five miles when the trip is made in the big scow patrol launch that the state department has placed on the river.

Paradise of Nature

Starting from Warden’s island, the long river trip to Bogil’s at Water valley, where the Monon road crosses the river, is one long paradise to the lover of nature and her pleasure palaces.

At this season of the year the first vivid colorings of the autumn intensify the verdure on the river’s bank. The glories that come hereafter are only, hinted. As if to make up for the incessant greens along the banks, however, the wild hollyhock and the waterlily and the “skunk cabbage” bloom in profusion and there is a little golden vine that forms a mat across leaf, frond and branch of any thing ft touches. Far down the river a little patch of this plant parasite puts a golden blur against the surrounding green with the effect of a great cluster of goldenrod. The foliage now is swiftly changing to a riot of color.

Many laughed last winter at a little provision of the new hunting and fishing law that was passed. It prohibited catching fish with the hands. It struck deep, at the root of market fishing in all Indiana rivers, but particularly it applied to the Kankakee, with its thousands of hollow logs and “bank retreats.” These were fruitful of big catches for the pirate fishermen.

Now the clam hunters—another of the natural Industries of the Kankakee—have become n factor in river life. The big dredge-scows of the clam men, equipped with long rows of wire hooks, not unlike “jackstones,” lay along the shores. The huge plies of clam shells on the banks, the steam-stove, dug in the ground, to heat the clams before they, are cut open, and the wide “opening table” testified that the bunters would return shortly.

One of these same bunters within the last day or two found a beautiful twenty-grain pearl. He sold it for $140. It was worth much more than that. Eight or ten hunters accompany each camp, several women being In the party. Each of the party averages $3.50 or $4 a day. Sales of pearls and sales of the clam shells to button factories are the sources of revenue. A carload of the shells sells for about seven hundred and fifty dollars, the usual price being $25 a ton for the shells.

Gifford Railroad

Leaving the clam hunters’ camp, the launch slides beneath the queer old bridge of the Gifford railroad, one of the most famous enterprises that the Kankakee region holds. The story of old man Gifford’s fight to make this road a success across the marshes is a story in itself.

On down the river the launch suddenly comes in view of Sandy Hook, and the boom of a great Krupp there, in the marshes would not frighten you so much as does the roar from the wings and throats of a hundred sandhill cranes. They rise from the reeds and snags and water lilies of the big inlet and darken

the sky as their wide wings spread. They have been feeding on the crawfish, frogs and other small, wild life in the “Hook. One old fellow, his neck as long as a man’s arm, sits moodily and watches the launch float by. He has seen men before, and they have not molested him.

Herons’ Nests

Back of Shanty Island for sears there has been one of the great heronries that have helped make the Kankakee famous as an Eden for ornithologists. In the nesting season the great birds make such a commotion at night. that it is often impossible to sleep within half a mile of the place. They build their nests high in the snags and forks of the swamp’s highest trees, and the picture is one to thrill when

a snake or a fox or some other prowler starts the whole colony squawking.

The encroachment of man into the Kankakee has, of course, meant the passing of much of the rarer wild life that used to abound here. For Instance, there are no more of the great white herons that used to frequent the breeding ground here. The whooping crane is almost gone. The blue herons, the, green herons and the night herons remain, however, with the hundreds of thousands of ducks.

Great South Marsh

Now the boat slides on to a stretch of river that is a veritable relief from the long miles of dense woodlands. Off to the left stretches the first sight of the great south marsh. Standing on the prow of the launch one may: see tot ten miles south a level green stretch of water vegetation. In this the ducks now are teaching their well grown youngsters how to evade man and catch the varied food of the marshes. Here to the spring, when the freshets come the marsh is full of pushboats, and the song of the twelve-gauge is heard in the land. Then comes the work of the state department with a vengeance. All day and far into the night the patrol boat puffs up and down the stream, and the sturdy deputies push across the marshes In search of market hunters or hunters using no license.

Commissioner Miles would stop the spring hunting of ducks in Indiana. He has been to Washington to take up with the United States authorities the question of how far an individual state’s regulative power over migratory bird shooting goes under the new legislation by which the United States department of agriculture is empowered to make rules governing “open” and “cIosed” seasons on migratory birds. _

Sought by Deputies

The launch has passed old Hank Granger’s place. Hank is one of the menof the marshes that Miles and his deputies have sought to catch red handed since the state department came under its present control. Only once have they been successful. Miles’s men say Grander runs a “blind tiger” in the marshes the year round.

The keen eyed woodsmen and riverman that Miles has brought into this northern county—Rod Fleming, Frank Lapham, John Rand and Cy Stout, Chris Mull, Jake Haver, Jake Bravy, Bill Fleeting, Harry Walker and many others—are slowly doing their work well. They are ridding the marshes and the prairies of the rift-raff that has made the place a slaughter pen for game and fish during the last decade. Men of few desires, seemingly imbued with regard for the law above all else, strong of arm, kind to a s fault, they are the sort that you would choose from a thousand if you were in danger.

Kankakee Fishing

The fishing on the Kankakee is perhaps then best on any Indiana stream or lake excepting only the Tippecanoe, which is, perhaps, better for bass.

The vicious dogfish, equally its hated by trite sportsmen as the muddy carp, seems to thrive, in the river, That is the only drawback to the fishing. And yet it is real sport to hook a ten pound dogfish. He fights as vicious as a bass. And he breaks more hooks and lines.

The pickerel are here—all about this camp they roll the water in the evenings and the early mornings. They sound like a herd of cattle in the water lilies when the moon plays on the padded bayous or a dash of rain brings down clouds of mosquitoes. The mosquitoes’ native land is here. They have pink whiskers, the old rivermen say. A little citronella usually will keep them from eating off your hat however.

Take Artificial Bait

The pickerel bite both in the river and in the ditches. They take the artificial bait of the caster as readily as the black bass in certain seasons. During the later summer months they do not bite as readily as earlier in the spring or in the brown days of September and October. They are biting here now and the Kankakee is far beyond , all others as a game fish stream. The black bass are here in abundance.

Then, for the still fisherman, there is sort a plenty. In, three hours fishing the very novice may take a string of a dozen or two “bullheads” channel catfish, large crappies, a black bass or two and many dogfish.

At night and in the early mornings the crappies and the bass and the “bullheads” bite readily Just in front of the Island here. Several fine “strings” have been caught off the dock this summer. Crawfish is the bait for this time of year, but the fish will take live minnows, worms or even fat meat.

In the spring time, when the channel catfish come up the river the state deputies place short poles deep in the mud along the bank of the ever and tie lines to these with bottle for floaters. Clam meat or beef or chub minnows are used for bait. In the mornings the pushboats travel between these poles and the fishermen take off the big fish. Some of them weigh ten pounds, some of them weight two pounds. All are big to the amateur.

In the bayous there is great sport for the caster. A new type of casting reel has come Into general use with Miles’s deputies. They al! are adapt with it. It lacks the complicated mechanism of the old style casting reel and it takes up much more line than the older type.

Rod Fleming, Miles’s chief deputy for the north, is said to be the moat expert caster in Indiana. He is typical of the class of men Miles has grouped about him. Although Rod is a cousin of state Senator Stephen B. Fleming the Ft. Wayne Democratic. leader, he is nevertheless, a Republican and had been all his life until be voted for Woodrow Wilson.

Politics Disregarded

Just to show that he Intended to pick expert woodsmen, of unimpeached integrity, for his force of game and fish guardsmen, Miles chose Fleming for the leadership of his men, although his politics were not of the right sort at all, Fleming had been with a former fish and game commissioner and had coma through the trying days of that administration with untarnished record. He knew the northern rivers and lakes. Most of all, he knew the Kankakee. He had two deep wounds in his thigh from the gun, of a “pirate.” He had numerous wounds which he had received in the discharge of his duty. Therefore, Miles made him chief deputy.

The life of the deputies is a hard one and an easy one. They are rugged because they are in the open air the year round. At certain seasons their work is light. At other seasons they wade through snow and ice and clammy water, for days and nights, or they pursue illegal fishermen across the waters of the Indiana lakes for miles. Or they pursue prairie chicken poachers across whole counties on the chugging motorcycles

The reward of their efforts is big in their eyes. They enforce the laws. They make arrests. They find that these arrests deter other “pirates” from pursing their illegal business. The stories of this camp at night, of the dangers that its men have gone through, would grace a volume of the rarest fiction. They eat much, sleep soundly, talk with quiet voices, see far, shoot and fish remarkably well and are generous.

Every man of them carries a state license in his pocket, which he has paid for from his own salary. Miles himself will not let his license run a day too long.

Miles gets a salary of $3,000 a year. His two chief deputies, Fleming and Jake Sottong, receive $125 a month. The remainder of the men receive $75 a month. Besides this they get reasonable expenses while they are away from home, which, is much of the time. Their money recompense is fair. Their health recompenses is large. And yet theirs is among the most dangerous vocations in Indiana.

Miles’s idea

Here is Miles’s big Idea: “Let the state of Indiana purchase a strip of land one mile wide on each side of the Kankakee river, from English lake to the Illinois state line,” he says. “Let it become a refuge and a breeding place for every sort of wild life in the state that will thrive there. Let the supervision of the tract be of the strictest. Let the ducks breed there in peace in the springtime. Let the trappers be watched with the keenest eyes for any signs of wholesale slaughter of the fur bearing animals.”

“Let the same war that has been going on against the fish pirates and the game pirates be kept up relentlessly until they are driven out. Let Indiana follow the lead of Pennsylvania, New York and many other well settled states and give its wild life a place to comparative peace. Let the old natural law of the survival of the fittest work out unhampered by man’s unregulated lust for killing.”

It is s no mere idle dream the state commissioner has dreamed. He has it all figured down to a basis that includes authorization by the Indiana legislature of the expenditure of some of the money now In the hands of the state commissioner for a start toward the completion of the big project. Later the state’s big game preserve could be added to as money in the department because available from sates of hunting and fishing licenses. by WALTER GREENOUGH