LITTLE RHODA AND THE WHITE ELEPHANT

By Fay Falsom Nichols

One morning in the fall of 1915, a west-bound Pennsylvania passenger train deposited among a group of travelers on the station platform at Kouts, Indiana, an elderly, whitehaired man. He was Ira Brainard, Pittsburgh businessman. There to clasp his hand in warm, genial greeting was a friend of long standing, Dr. Phillip Nolan, the town’s practicing physician.

The two men drove slowly out of town, the doctor’s car chugging along over a wash-board gravel road. Mr. Brainard had come to dispose of the holdings of the Pittsburgh Hunting club at Baum’s Bridge. These included some six hundred acres of land at Prairie Bend and Garrison’s bayou, a sizeable club house at the bridge, silverware, linens, household furnishings and the Little Rhoda, an outmoded steam launch. Because Brainard was the last remaining member of the club, his was the obligation.

The old man was closing the books for a group of Pittsburgh men, who, years before, had learned that “for real company and friendship, there is nothing outside of the animal kingdom that is comparable to a river.”

Today there is no spot along the River more redolent with memories than Baum’s Bridge. The earliest recorded chronicles set it down as the Potawatomi Ford, a place of great strategic value, as it commanded the only place the Kankakee could be crossed for many miles up or down the stream.

Here the Potawatomi intrenched for the boundary war -the only known battle to take place on Porter county soil-fought with neighboring Western tribes upon Morgan Prairie. For many moons there had been between these Indians disputes over boundary lines. Finally it was agreed between them to take up arms, with three battles, only, to be fought. The victors in two of them should be the conquerors.

The Potawatomi assembled in great numbers at the ford. On the first day of battle, leaving the greater part of their warriors in hiding, the leader decided to deceive the ford by a display of weakness. After a short battle fought to the north of Morgan Prairie, they wheeled about and fled back to the river. The enemy sensed an easy victory.

At the next battle the Potawatomi strained every nerve. Every warrior was in line of battle. Only the women and children were left at the ford. The enemy had been duped by the first showing and lacked strength of arms. The Potawatomi chased them back to Garie’s River and became the possessors of the Kankakee area.

We next hear of this place as the crossing for the Allen Trace, mentioned in an earlier chapter. Then in 1836 came George Eaton and his family. This intrepid pioneer erected his log cabin high on a sand ridge overlooking the River and set about to build up his fortune by operating a ferry—Eaton’s Ferry.

In 1833 the Commissioners of LaPorte county had authorized Matthias Redding to run a ferry across the Kankakee on the line of the Yellow River road. This was just a few miles above the Potawatomi Ford.

Passengers were ferried from the Porter county side to the sand ridges of jasper—as Dan Sigler used to say, “Over Jerdon”—and usually there was a waiting list for the return trip. The distance at most seasons of the year was about a mile and a half. Part of the way was a trackless, dense swamp. In 1846 the government established a mail route from Michigan City to Rensselaer, and the Eatons were granted the contract. In dry seasons the trip was made on horseback, the horse swimming the river. Winter posed a problem with varying freezing and thawing periods, but the Eatons must have been equal to the task, for there is no recorded dissatisfaction as to the service given.

In 1848 the boatman built a toll bridge, felling the heavy timbers adjacent to the crossing, and sinking them well into the river bottom. It was the first bridge built above Momence. The following summer the bridge was burned. Again, Eaton resorted to the ferry, operating it until his death in 1851.

A man by the name of Sawyer came into possession of the ferry at the death of Mrs. Eaton in 1857. The same year he built a bridge, but it was not substantial enough to withstand the ice gorges, and high water the following spring took it out.

Sawyer also operated a saw mill and rafted logs down the river. In 1860 he sold his business to Enos Baum, who finally built a substantial toll bridge.

The people of any community have their own way of directing strangers to certain locations. Dr. Nolan and Ira Brainard needed no one to direct them to Baum’s Bridge. They were traveling a familiar road. But should you inquire your way there, you would be told to take State Road 8 to Trinkle’s Corners, the cross roads south of the Trinkle cemetery-this, regardless of which end of the highway might be your starting point-then turn south and go straight to the River.

The word straight, however, is a paradox. The road is winding. Just before you reach the bridge it would seem you were coming to a dead end and about to crash into the sparkling windows of Jimmy Collier’s white frame store. This is because the old riverbed made a turn here, and wasn’t disturbed by the river-straightening program as the dredges plowed their way down stream. The big ditch, as men began calling the new channel, passed a short distance to the south.

Jimmy paints pictures. In oils and water colors. Sentinellike cat-tails lifting brown, cylindrical spike heads at the edge of a bayou. Graceful Indian princes and beautiful princesses beside frothing water falls. Wolves and other wild life.

It is a very special privilege to have Jimmy show you his pictures. A mutual friend must pave the way. Then the artist will bring unfinished canvases from the upstairs room where he works, pleased no end, if the visitor expresses pleasure in his work.

Jimmy has never exhibited at the Hoosier Art Salon. But not from lack of merit in his pictures. It is because no picture is ever entirely finished. He works painstakingly and exactly, but spasmodically, seeking neither fame nor fortune. Some day-he will tell his guests-he expects to finish all of them. Even he will decorate the walls of his store with murals telling the story of the River. It is a delightful dream, piquant in imagery.

What brought Jimmy to Baum’s Bridge? His father, E. C. Collier, of Brook, Indiana, built a thirty-five foot cabin boat to take his family to the St. Louis World’s Fair. The boat, propelled by a twenty-horse power gasoline engine, was launched on the Iroquois River, and christened for that stream.

After the Fair, Collier thought to operate the Iroquois as a pleasure boat up and down the Kankakee, from Baum’s Bridge to Momence. However, the little craft drew more water than the river had at most seasons of the year. When the water was low, navigation was impossible. So, eventually the boat was sold, and finally came to its end in a storm off the Dunes beach on Lake Michigan.

The parents died. Jimmy was left alone, to idle away the years with paint and brush. To sell a little tobacco and fishing equipment and dream. Mostly to dream.

After the trees were slaughtered, Jimmy could look up at a subtly etched, raisin-blue sky where, with spectral ink, had been silhouetted a mighty avian life. He could see a canopy of trees that once arched the roadway in front of his store so dense with foliage that only, when the sun came up in the morning, or teetered on the rim of the horizon of an evening, was it able to so much as get a peek at the road.

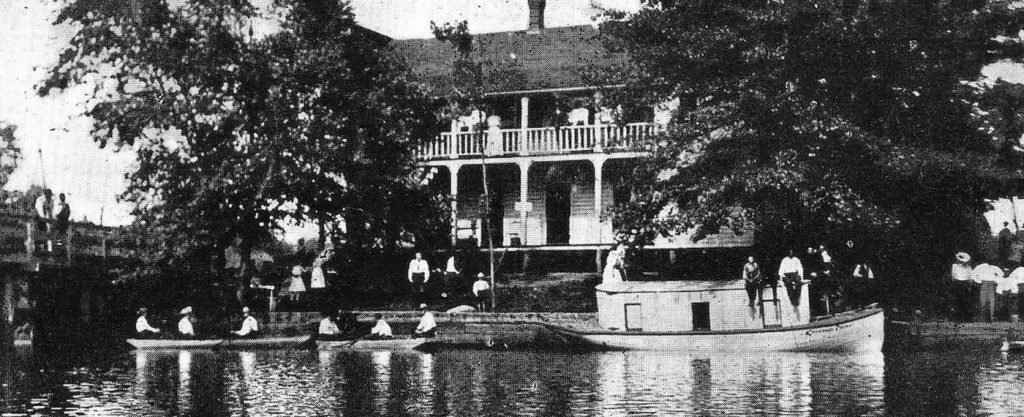

At this magnificent spot the Pittsburgh Club chose to erect a club house. Here the banks e unusually high, the River, itself, performing decorously. Near-by, on sand ridges, were the modest cabins of many local folk who came here often for hunting and fishing. Later, there were the pretentious quarters of the Valley Gun Club, the Rockville Club, and the Louisville Club.

A tradition survives that it was some distance above the bridge at English Lake the Pittsburgh men first made contact with the Kankakee. Management of the club was mostly in the hands of three men. Harry and Joe Wainwright and Ira Brainard. Joe was president of the Arsenal Bank at Pittsburgh, and also was in partnership with his brother, Harry, in operating a brewery. Their grandfather had been one of the original stockholders of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Brainard managed the Pittsburgh branch of a large New York packing house, and held a controlling interest in the Pittsburgh Novelty Glass Works.

Rivermen chose to think of them as men of means, and those engaged in various capacities during the hunting season liked to brag about the sportsmen’s generosity. “Paid five dollars a day, whether we worked or not, during two months in the spring and same in the fall,” they’d say.

The Panhandle branch of the Pennsylvania penetrated the Kankakee marshes at English Lake. This stretch of road was known as the Peg railroad, because engineers, contrary to all known railroad building science, had built the tracks on high trestle work through water and bogs. The club men first came in their own private car, which was parked on a siding for the two weeks of vacation. Later they lived in a houseboat, renting river frontage from Old Man Pugh.

One day when George, their colored cook, was dressing mallards, he found their craws filled with acorns. Everyone wished to know where the oak trees grew. Harry Wainwright and Mr. Brainard set out down the river in a rowboat on a scouting expedition.

They sighted the high banks at the bridge. Here were the most magnificent oak trees to be found any place along the River.

“We’ll stop here,” said Brainard, “and see about a place for a club house.”

“I think we’d better go farther down. Might strike a spot we’d like better,” contended Harry.

While the two men argued, their boat spun round and round with the current. Twilight was coming on and neither of them was familiar enough with the river to care to be on it after dark. Finally, they compromised after noting a cabin on the near-by banks, and pulled to shore.

It was at the George Wilcox home they spent the night. Familiar with the stream from head to foot, Wilcox convinced them of the advisability of locating at the bridge. He helped them in their selection of marsh acreage, and became the year-round caretaker for the club house they erected.

The Little Rhoda, their steam launch, became a familiar sight on the water. It had a vivid green canvas top with scalloped edges, and looked the pleasure craft that it was. A club member named Young was always in charge of the boat. Because of the high silk hat, black bow tie and shiny black suit he wore, he was a noticeable figure among the roughly garbed river men. Like all club members he was, at all times, most courteous.

When reminiscing about the Pittsburgh Club, there is one day that stands out in the memory of the farmers for miles around the old bridge. It was October 8, 1888. That memorable day was discussed the whole winter long in farm kitchens, at rag-bees and quilting’s, and in parlors over a cup of tea when the minister came to call. It had been a huge success, and its highlights would be handed down to their children’s children.

On this day they had been the chosen guests of the club. A week in advance, Mr. Brainard went about issuing invitations to residents living as far as five and six miles distant, driven over the roads adjacent to the river by Mr. Wilcox in his buckboard, two sturdy sorrels drawing the steel-rimmed wheels laboriously through deep, loose sand.

Never before had the people eaten such fancy breads and cakes; such delectable cold cuts of smoked and dried meats! All the beer a man could drink!

Dancing had been arranged for the afternoon in the huge common room, but the hand organ, which was to have furnished the music, disappeared. While one of the Wainwrights was trying to locate the organ Mr. Young shoved off in the Little Rhoda-a group of ladies in white muslins and figured calicoes, comfortably seated under the green canvas-for a trip down the river. As the boat rounded the bend the organ tunes of “Good Bye, My Lover, Good Bye,” floated tantalizingly back over the water.

Local rivermen who pushed boats through the marshes for the clubmen like to recall Old George, the colored cook, and his kettle of soup. George kept this pottage slowly simmering on the back of the big steel range. No matter what time, night or day, the men, their bones chilled to the very marrow, from long hours on open marsh, or cramped down in tin hunting tub and blind, came in, George, with his bowls of the warming concoction, was waiting.

“Never, in all my world travels, have I found a more perfect spot, nor a more tantalizing river,” said General Lew Wallace, Hoosier soldier and novelist, when he located at the Bridge.

Wallace arrived simultaneously with the Pittsburgh men, and purchasing a half acre of waterfront adjoining that club’s property, proceeded to build a long shed to shelter his house boat, the White Elephant. At Ox Bow Bend, a short distance from the bridge, the General took up section seven, six hundred and forty acres of marsh land, as his own private hunting and fishing ground.

When he desired seclusion and quiet, a steam launch pulled the White Elephant to the Bend. Here, on its deck under the green canvas top, he spent long hours plotting and writing, content, quiet, with the solitude and beauty about him.

Although, over a period of years, little stories have been continually popping up that the novelist wrote his immortal “Ben Hur” in Old Mexico, in Colorado, and at his home in Crawfordsville, Indiana, it is a known fact that he was encamped at the Bridge when the telegram came from his publishers informing him of their acceptance of the novel. And, no doubt, judging by the size of the book, and the wandering feet of the author, parts of it were written in all of these places.

When at the Bridge, if the General craved companionship, there were his friends, John Benkie, Kouts druggist, with whom he liked to share an evening pipe, and Mrs. Benkie, vacationing with their children at the river. There were judge Winfield and Dr. Thomas of Logansport, up for some fishing, and Miss Ella Parker of Chicago, staying at the Wilcox home and in whom he confided that he had written thirteen chapters of “The Fair God,” while here.

There were his Indianapolis and Crawfordsville friends to whom he extended an occasional invitation to join him on the White Elephant. Their entertainment he turned over to his son, Henry, but their comfort and wellbeing he placed in the hands of his competent colored cook and handy-man.

Probably the General hadn’t intended his last visit to the Bridge to be the final one. He had left the White Elephant and her furnishings in the hands of his caretaker, George Wilcox. Wilcox pulled her up on the dolly and into the shed. Here she rested high and dry, and with the changing of the channel, there was no putting her back in the river.

A Baum’s Bridge native finally came into possession of the boat and planned to exhibit her, but “folks here’bout,” claim that Henry Wallace, the son, refused him permission. So, the little craft with the steel bows that supported the colorful awnings and folded up for “low bridge,” fell to pieces with the years, and was finally carried off, piece by piece.