Sighting the Stars in Transit

by: Fay Folsom Nichols

IT WOULD STORM in three days. Last night the moon floated in a prismatically colored, three-hinged circle. This morning the entire eastern sky flushed violently, warningly red, and then sank below a bank of cold, forbidding clouds. These were the signs! They must make haste!

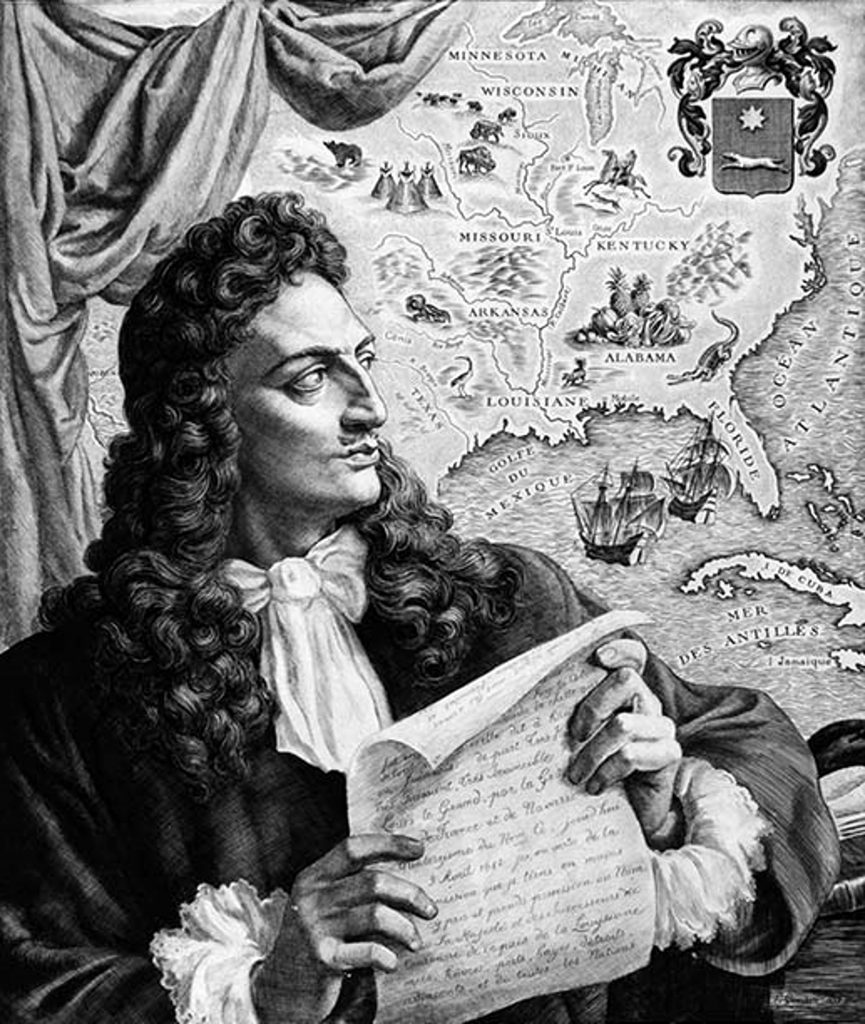

Sieur de LaSalle, red-coated and fur-capped, stooped over to tighten the deer thong that bound fur-lined moccasins to his leather breeches, then straightened to his full commanding height. He inspected the activities of his men busily reloading canoes for the second stage of a long journey. He urged completion of the task. Too long now had they tarried! The weather threatened! Days were growing shorter. Nights longer!

LaSalle and fourteen carefully selected men, traveling in four heavily loaded canoes, had landed at an appointed rendezvous on the River of the Miami (St. Joseph) on November 1, 1679. The trip down from Green Bay, traveling along the western shore of Lake Michigan, had been a series of near accidents. They had left the islands in a beautiful calm, but half way across the lake they were stranded twice because of the storm. It was only by the greatest of miracles they had been able to reach their set destination.

After such harrowing experiences and with their food supply running low, the men were beginning to consider their leader harsh and unreasonable. Reluctantly they had felled trees for the new fort LaSalle felt necessary to be built at this point.

Father Hennepin, Jesuit priest, had for days been urging that the party move on. The aged Father Gabriel had fainted several times from lack of food.

LaSalle waited for two reasons. First, Henry de Tonty, his faithful lieutenant who was supposed to have been waiting for him at the rendezvous, had not arrived. Together with twenty men in four canoes, Tonty had left St. Ignace routed by way of the eastern shore, a shorter route. He was to proceed to the mission post at Sault Ste. Marie to catch and bring in two of their men who had run away from service.

Second, the Griffin, his prized fur-laden boat, which had put out from the post at Mackinac bound for the Storehouse at Fort Niagara, had not been heard from. _ He was sorely in need of the supplies the boat was to bring on its return trip, together with men newly arrived from France who were to strengthen his cortege.

Only yesterday as he struggled to perfect the map he was making, scolding Pierre because the berry juice had frozen and turned to water, finally throwing his quill into the fire, he had been nervous and distraught to the point of rage. He had waxed and re-waxed his heavy moustache as he strode about the room. It wasn’t pleasant to recall his late upsetting experiences of having been lost in the surrounding forest and where, but for the grace of God and White Beaver, his faithful Indian guide, he might still be.

Toward evening LaSalle strode down the bank to where he had sounded the river’s mouth and marked either side with two tall poles, from which floated bear-skin pendants. He watched the line of buoys bobbing well out in the water that would give Tonty his bearings.

Suddenly one of the men had given an ear-splitting yell, and LaSalle followed the hand that pointed riverward. Did he see boats moving in the distance? He shaded his eyes with his hands. Yes l Surely, through the fog that was falling, canoes were slowly approaching. The men at the paddles appeared almost exhausted. He motioned his own men out into the water to lend a helping hand.

“The Griffin! What about the Griffin?” LaSalle questioned Tonty. “Do you bring me word?”

“No word, Commander) We fear she has gone down in the heavy seas,” was the lieutenant’s reply.

Although still concerned over the Griffin, LaSalle had apparently slept well with the worry over the safety of Tonty and his men removed. The loading was proceeding without interruption. But, as he directed, last night’s dream still haunted him.

He had been back in his beloved Rouen, capital city of Normandy, his place of birth, walking along the fogdraped wharf. He was Robert Cavelier, son of a rich and influential merchant, bidding his older brother Jean, about to leave on his priestly mission, an envious farewell. He was waving to sailors and adventurers with whom he had visited, ready to set sail for the -New France, wonderland of the world.

Tucked inside his rich velvet coat was a little book of the Jesuit Relations containing the latest adventures of the missionary priests among the savages of the American wilderness. Jean was to be one of them. It set the young boy’s heart afire.

He was back at the Jesuit Seminary continuing his study of physics, astronomy and higher mathematics. He was binding himself to the order and later seeking to be released by the church.

He was on the rough, uncertain Atlantic, enroute to join his brother at Villa Marie. He was twenty-three, full of hope for the task he had set himself, and with plenty of funds.

Now he was signing his name Rene de LaSalle. He was at last in the harbor of New France, setting his feet for the first time on strange soil. The French vessel rode at anchor in port for an exchange of goods with the French trader and the Indian. He was watching bales of fur being stored in her hold, and Indians bartering for the knives, gaudy cloth and bright colored beads.

He was aligning himself with the Comte de Frontenac, the King’s territorial governor. He was back once more in France, pleading with the government for funds to continue his search for a short sure road to Cathay, promising to fill the King’s coffers with gold from these fabled lands.

This morning as he paced the path between the flat topped redoubt and the bay, where the canoes tossed restlessly, France and King Louis XIV seemed very far away. Once he had filled his pockets with day dreams. How much farther must he travel before realizing theml

Tonty gave the sign. Eight canoes were ready. Thirty men waited for the word to dip paddles. It was the third day of December.

He was leaving a garrison of four men in the fort of the Miami, with directions to the recruits expected on the Griffin for following. LaSalle and his men paddled southward through the waters of the St. Joseph. His friends, the Winnebagos, had often repeated a tale of a beautiful river.

… “Great Father of all Rivers.

Beyond New France was an unknown continent where a white man’s foot had never trod. Through its mysterious forests a great river flowed westward to the Vermilion Sea. The adventurer sought its source. This was the reason he had left the rushing Lachine rapids, and abandoned his task of establishing a feudal seigniory. An urge, stronger than life itself, drew him out. He, Rene Cavelier de LaSalle, would connect the waters of the great inland lakes with the waters of the Gulf and be on his way to the China Sea.

The English had established a settlement in Virginia in 1607; the Dutch, thanks to Henry Hudson and his Half Moon, had colonized Manhattan in 1614; Spain was setting tentacles in the southeast; but this great inland water route and all the territory through which it flowed the explorer would claim for his king. It should be the Great New France. He became intoxicated with the possibilities that seemed at hand.

Lead deposits that would yield two parts ore to one of refuse only waited the miner’s pickl Furs, soft and luxurious, fit for the queen and her ladies-in-waiting! Father Hennepin should write back of these riches, of the pheasants as there were in France; quail, deer, the finest vines which produce vast quantities of excellent grapes!

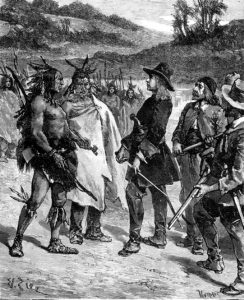

Friendly Indians had provided the Sieur with braves to help him through the vast, uncharted wilderness which’ he must traverse. Strong, sinewy Potawatomi youth, brownskinned and fearless, would break portage trail and help paddle-to-the-sea. White Beaver would be his guide and constant companion.

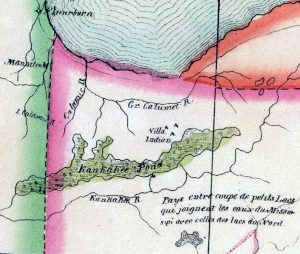

It was a two day journey down the St. Joseph before the canoes rested in the south bend of the river. Here began the portage to the Kankakee.

From the top of a tree-clad bluff, LaSalle looked out across an open plain. His feet set out to follow a path scooped out by uncounted buffalo hoofs and moccasined feet.” The ground, which through most of the year oozed under the feet of those who made the portage, was frozen and hard. It was a good time to travel.

Canoes were unloaded. The guides shouldered them and picked up the portage path. The voyageurs took upon their backs the sawyer’s tools, the forge, the iron for the ship’s hull LaSalle planned to build once the Mississippi was reached, arms, ammunition, goods for barter with the Indians, and the scant remaining supply of food.

Hopefully he watched his men as they reloaded their canoes set down in a small meandering creek the Indians informed him was the beginning of the river. How close were they to mutiny? Only success, he felt, in finding wild meat to replenish the rapidly diminishing larder might prevent it.

Shell ice hugged the banks and the paddlers pushed out into the middle of the stream in search of the down current. Gradually the waters widened and spread out among charred reeds and half burnt brush.

Although the current was swift, the river twisted and doubled until at the end of a day the boats had progressed little.

The Indians had promised the Kankakee area would be abounding in game, an unfailing supply of meat. LaSalle expected much. But again disappointment came as a particularly heavy blow.

Fall fires had taken all vegetation in mad, greedy sweeps. One lone buffalo, still alive out of a herd that had sunk in muck bottom lands, was pulled from the hole with chains, its meat sustaining the men a little longer. They pushed on.

Toward the end of December they had navigated the Kankakee from its source to its confluence with the Des Plaines, and continued on down the Illinois. Could he urge. his men a little further! On to a southern land of soft breezes, lush vegetation, wonderful edible fruits . . a veritable Garden of Eden! He played upon their imaginations.

It was thirteen years since he had first landed at Villa Marie. He liked to think in retrospect. The Ohio he had visited alone. The waters of the Wabash had lapped the sides of his canoe. The wild beauty of this entire unparalleled land beckoned him. He spread his arms out in one majestic sweep. All-all this great region from the Great Lakes to the Gulf-he would take in the name of France.

With fresh enthusiasm he set some of his men at the task of building a fort, Fort Crevecoeur. On a high bluff he chose the site for the first fixed establishment of the white man. It would be the big cache between St. Ignace and the Gulf. To others he gave the more particular work of building the forty-two foot vessel that would be used to complete the expedition down the Mississippi.

He marked his map. The journey down the Siegnelay had been accomplished. He still felt the spell of contentment as flickering light from campfires reflected upon its waters; the mystery of shadow; darkened bayous, the beauty of stars dropping from steel blue heavens into its gleaming current.

Evidently the explorer was well satisfied with the St. Joseph-Kankakee waterway, and the Kankakee served a very definite purpose. It appears to have been a shorter and less difficult route to the Mississippi as it wound temperamentally through the ancestral lands of the Potawatomi. He is known to have passed this way many times after his journey of 1679 as he endeavored to establish a line of French trading posts from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf.

Though often doomed to disappointment in the years that were to follow, his enthusiasm and aspirations never lessened. The loss of the Griffin was the earliest of maritime tragedies on the Great Lakes. It was only one of many dofeats he was forced to undergo as he tried to assure the Indians of French support, to make peace between the Illinois and the Miami, that they might unite against the aggressions of the troublesome Iroquois and set up French trade in the richest valley of the world. A large bronze tablet in Highland cemetery in the city of South Bend today marks the spot of the Council Oak where he brought representatives of these tribes together.

Suppositions and imaginations supplant scanty records, but the historian notes that in 1684 LaSalle was back in France, laying before the king’s council his plans for the occupation of the Mississippi Valley. His petitions granted, in January, 1685, he reached the Gulf of Mexico with the new expedition under his command. His navigators missed the mouth of the Mississippi, and the company landed on the Texas coast.

A new fort was erected, but disease, famine and desertion of his men got in telling blows. A jealous deserter claimed the life of the explorer on the banks of Trinity River, November 10, 1687. No monument marks his burial spot, for his body was stripped of its clothing, and the buzzards claimed his flesh.

LaSalle was forty-three years old when death came. But during those twenty years that marked the height of his career, he placed a domain larger than all Central Europe under the scepter of the French king.

The entire middle region became a land of controversy. LaSalle had taken it in the name of the French Crown. England coveted the Northwest for its furs. Thus the two countries became the chief wranglers for the North American continent with France in complete control of both sides of the Mississippi. The French occupancy was interfering with the western movements of the English colonies in from the Atlantic coast.

Came the French and Indian Wars (1754). Then it was the blood of the English flowed with that of the French to drain into rivulets of Indian blood over a period of years of tribal wars. Echoes of the white man’s muskets carried in over our valley, and the shafts of the Indian’s arrows buried their flints deep into its very soil.

As early as 1763 France was doomed, so far as her hold on the North American continent was concerned. She had lost Canada and her territory east of the Mississippi to England. Her men were primarily explorers, men of God, and tradesmen. She was forced to cede her land west of the river to Spain for the latter’s inefficacious help. Slowly, but surely, she lost her hold on the land her people were learning to love. Their Acadia.

In 1781, Spain tried to establish dominion over Detroit and the Great Lakes. She was laying claim to all lands drained by the Mississippi and her tributaries, holding forth that such was the right of a nation occupying the mouth of a river. Hadn’t Pope Alexander VI granted King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella the territory due to Columbus’ discovery)

The new Spanish commandant at St. Louis, Cruzat, outfitted an expedition. There were thirty Spaniards from the Fort, twenty Cahokians, joined later by twelve additional Spanish soldiers, who had been sent up the Illinois River, and by two hundred Indians.

Up the Mississippi, the Illinois and the Kankakee to the beginning of the Old Sauk Trail, went the army, then north by land to the Big River St. Joseph. (Near the present city of Niles.) The post was without a garrison. It was captured and the goods divided among the members of the party. Up went the Spanish flag, to fly over the Fort for twenty-four hours.

Then General Don Eugenio Pourre turned heel. He headed his regiment back along the lake. It floundered through the sand dunes, so recently crossed. Drawing rein on the edge of the hard-packed, clean-washed beach, he sat looking out over a broad expanse of water. White caps rolled along on the crest of the incoming tide, deepening the blue of the lake.

The chill of the lake-borne north winds struck Don Eugenio to the very marrow of his bones. His men were shivering. He pushed back through the confused mass of scrub oak that flanked the narrow ravine over which he had made his way to the beach.

What did Spain want, anyway, with this god-forsaken country? Let the Indians have it-the French or British, for all that it mattered. A Spaniard was born to live under blue skies. The sun of the southlands should warm the cockles of his heart. The Spanish king had nothing to worry about! Didn’t he control all of the territory west of the Mississippi to the blue Pacific. What more could he want for colonization! Don Eugenio hurried back and reported to the King there was nothing worth taking.

Thus the fate of the Kankakee Valley was finally sealed. As a part of the great Northwest, later she would be included in that wonderful region, the Midwest. Her prairie lands would be settled not by her explorers, the Frenchmen; not by the dashing, warm-blooded Spaniard; not by her cold, calculating conqueror, the English, but by the Yankee and the Southerner, the native-born Americans who had developed from a fusion of many peoples during her formative years.

(1) LaSalle reenactment 1979 – YouTube