Draining the Swamp

By John Hodosn

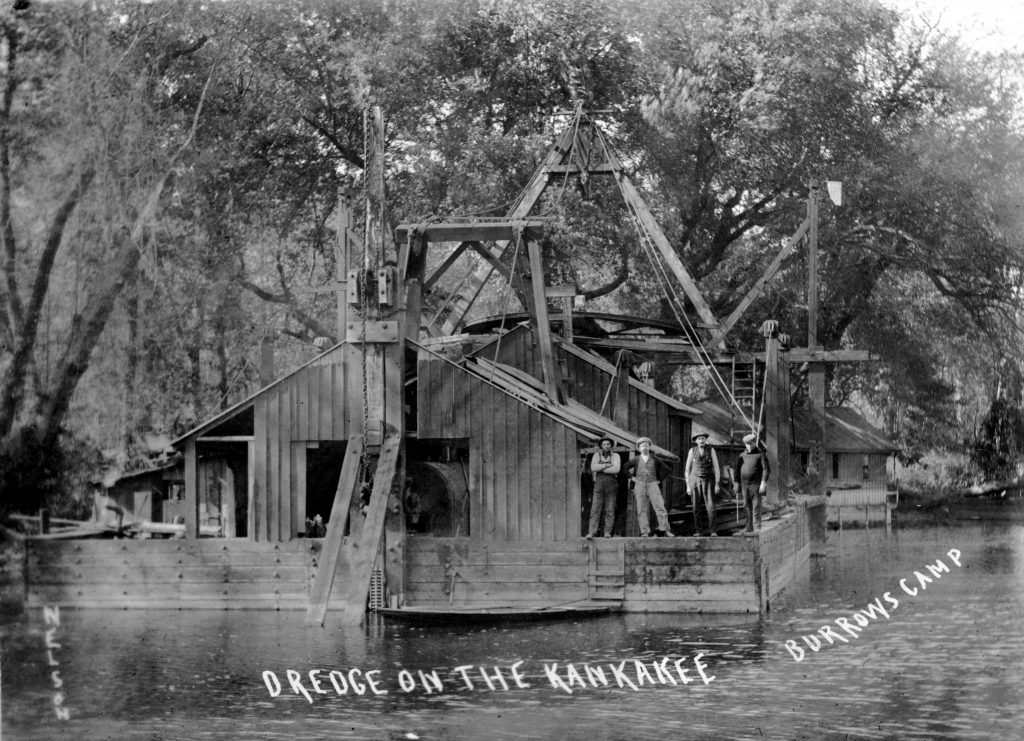

In “Pioneer Hunters of the Kankakee” J. Lorenzo Werich dedicated one chapter to “Draining of the Swamp.” To Werich the Kankakee Marsh was a paradise that man destroyed for the sake of short term gains. Born in 1862 Werich was able to tell the story of the pioneer hunters and trappers of the Kankakee and also lived long enough to witness its destruction through channelization. What was once known as the Everglades of the North was reduced to a 97 mile drainage ditch.

Werich wrote that in his youth, for the uninformed, “any mention of the Kankakee Swamps called up visions of a region of limitless extent of swamps and marshes, uninhabited and desolate, a country always associated with tales of suffering and death.” Today we know that a marsh is an engine for water purification and the habitat for a wide range of wildlife in such great numbers that it was the natural home for Native Americans soon after the last glacier retreated. Later it would attract the trapper and hunter for its seemingly endless bounty. The pioneer farmer would follow establishing homesteads and settlements throughout the marsh high grounds. Then came the greedy land speculators and corrupt government officials that only saw the Kankakee Marsh as a worthless land ripe for ravage.

Werich wrote: “all great movements have their beginning. So it was with the drainage of the Kankakee Swamps.” In the 1850 the U. S. Congress passed the Swamp Land Act that ceded swamplands to the states they rest in. In 1853 Indiana made its first attempt to drain Beaver Lake, which at that time was the largest lake in Indiana. By 1880 it was gone. The state plan was that land sold after “reclamation” was to be sold and the proceeds to be used for infrastructure. Very little money ever made it back to Indianapolis.

For Werich the draining of the Kankakee marsh was more than the loss of one of America’s greatest natural resources. It was the loss of an entire way of life for all that preceded him. It also necessitated removal of the Native American from the Kankakee Valley. Indiana would never be able to drain the swamp as long as the Native Americans held claim to any land within the marsh proper.

In 1881 Werich journeyed to the reservation where the Pottawatomie were resettled in Kansas “that I might be able to learn more of the early history of their hunting grounds on the Kankakee River.”

After a lengthy visit Werich returned home, forever changed by his visit. What Werich learned transformed his views and created a special kinship for him with the Native Americans and their way of life.

He later wrote: “As I was about to leave one of the old warriors rose to his feet, saying in a low, sad tone: “Oh gone are the days of my youth and memories of my people and the beauties of our beautiful land are forever buried. My Father and myself are forgotten, and the Land of Liberty shall know us no more. When I visit the scenes of my boyhood where 1 played with the pebbles and sand, where years before played the little papoose with his canoe and paddle, and when I recall some of my early adventures of hunting and fishing, the most pleasant recollections of all was my boyhood days at my island home on the Kankakee.”