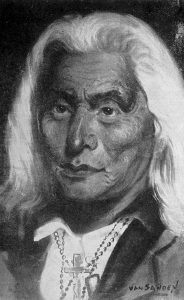

Chief Leopold Pokagon

By John Hodosn

May 14, 2015

Leopold Pokagon and his son Simon are arguably the best well-know Potawatomi Chiefs of the St Joseph and Kankakee Rivers area. Pokagon took the name Leopold after being baptized Catholic in 1830. Pokagon was born in 1775 to a Chippewa father and Ottawa mother. He was taken captive by Potawatomi Chief Topenebee and became Chief after Topenebee’s death in 1826. Pokagon translates as The Rib. He was given this name because a human rib was found in his scalp lock when captured.

The early 1800s were a transitional time for the Potawatomi. White leaders in the Michigan Territory were enticing pioneers in order to fulfill statehood requirements—the Indian was resisting by all means available to them. This resulted in a clash of cultures that had to be settled. The Fort Dearborn Massacre of 1812 was one consequence. Pokagon was present and later professed that “firewater” was the main reason for the attack. Pokagon could see how this conflict would end and worked to see his tribe retain a home in their ancestral native land.

In the early 1800s a series of treaties were signed between Native Americans and the U. S. culminating with the Treaty of Chicago in 1833. These treaties are too extensive to be covered in this column. After the Indian Removal Act of 1830 was passed, Pokagon struggled to find a way for his tribe to remain in its native homeland. Nearby Catholic missions had been established for hundreds of years and Pokagon came to realize that if his people were Christian they may be allowed to stay. In 1830 Pokagon traveled to Detroit and visited with Father Gabriel Richard and requested a priest be assigned to his tribe. Later that year Pokagon and his wife were baptized. In August of 1830 Father Stephen Badin was appointed priest for Pokagon’s Potawatomi. After conversion, Pokagon’s tribe became known as the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi. Now being recognized as Christianized, Pokagon was able to have the Treaty of Chicago amended to allow his tribe to remain. All other Native-Americans were resettled west of the Mississippi. This removal ended with the infamous Trail of Death in 1838.

From the sale of a large amount of land to the government, Pokagon was able to purchase one thousand acres in Cass County, Michigan. His tribe—The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi—relocated there in 1839 and remain to this day. Leopold Pokagon passed away in 1841. He was succeeded by his son, Chief Simon Pokagon.

Pokagon band of Potawatomi avoid removal

By John Hodson

Jun 11, 2015

Most Native-Americans were relocated west of the Mississippi by 1840. However, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi avoided removal. I want to thank Dr. Mark Schurr for contributing to this column.

In Indiana, treaties between the Native-Americans and the U. S. government began with the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 and culminated with the Treaty of Chicago in 1833.The Indian Removal Act signed in 1830 authorized the federal government to negotiate treaties with the purpose of removing all Indians to lands west of the Mississippi.

Potawatomi Chief Leopold Pokagon came to the belief that if his tribe would convert to Catholicism it would be allowed to remain. In 1830 Leopold traveled to the Detroit Diocese and requested a “black robe” to be assigned to his tribe. Pokagon and his wife were then baptized by Vicar General Father Frederick Rese. In late 1830 Father Stephen Baden established the mission to serve Pokagon’s tribe, afterwards the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi was officially recognized. Catholic Indians and those willing to convert joined Pokagon’s tribe.

Pokagon’s tribe had claim to around 1 million acres of land in Southeast Michigan, Northwest Indiana and the area in Illinois around present day Chicago. Pokagon was leveraged into selling all of his lands for a paltry 3 cents per acre— collecting the funds presented a problem.

With the initial annuity payments Pokagon purchased 874 acres in Cass County, Michigan. Father Badin then petitioned the government to amend the 1833 Chicago Treaty of Chicago to exempt Pokagon’s his tribe from forced removal. In 1840 the Michigan Supreme Court decided that Pokagon’s Catholic Potawatomi were protected from relocation. Leopold Pokagon’s victory was short lived before his death in 1841. Pokagon’s successor—his son Simon— was required to secure his tribes rights and establish their new home in Michigan.

I believe Simon’s mother’s wisdom to have him educated in the ways of the white man in white schools is what gave Simon the foundation to deal with the roadblocks he faced completing his father’s work. His first hurdle was to persuade the government to honor their payment obligations. He realized success eventually, but it was not until 1896 that the government finally made good on its debt—nearly 50 years after the sale! Although, Simon died in poverty his descendants, because of his efforts, was later to build the Four Winds Casino in New Buffalo, Michigan securing his tribe’s financial security. In 1994 President Bill Clinton signed legislation affirming The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi sovereignty. Not all Potawatomi were able to save themselves from the “Trail of Death.” My next column will address this.