By John Hodson

During the Civil War, railroads began crisscrossing the Grand Kankakee Marsh. With the advent of this transportation service people from across the world could enjoy this “Everglades of the North.” Thus began what I refer to as the Sportsmen Era of the Kankakee. Soon clubhouses were being

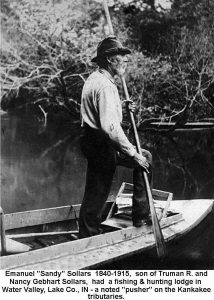

built throughout the Kankakee Marsh by business and civic leaders of our great nation. By the early 1900s many of those private hunt clubs were being sold into private ownership. Many the former clubhouses were now private homes or businesses servicing the needs of individual hunters. Growing attraction to the adventure of hunting the Kankakee Marsh created a demand for experienced “Pushers.” The shallow depth of the Kankakee required many of the Kankakee boats to be pushed with long paddles instead of rowing; hence the term “pusher” sprung. Previously, many of the clubhouse hired managers who also acted as guides for the sportsmen. Now, numerous pushers opened their homes to hunters for lodging and act as guides.

On March 6, 1904 the Indianapolis Journal ran a story titled “Duck-Hunting Season at Hand and Sportsmen Prepare for Outing’s.” The article began: “Duck hunting is one of the things not carried on extensively around Indianapolis, except along White River, and when the ducks begin to fly hunters can be seen along the banks and out in boats. However, the majority of local hunters go to Water Valley, which is on the Kankakee River, where the sport can be enjoyed in the right way.” The Journal hired renowned guide Sandy Sollars to pilot the reporter.

At the beginning of the 20th century America was prospering to the point that the average man could now afford to take part in hunting activities; previously only affordable to the rich and famous. This resulted with an influx of inexperienced waterfowl hunters flocking, pardon the pun, to the Kankakee Marsh. I personally have waterfowl

hunted, and continue to deer and turkey hunt. I subscribe to a few hunting magazines and mailing lists of popular sportsmen catalogs. Each is filled with the newest products to prepare the sportsmen for the upcoming hunting seasons. It was much the same for the hunter of early 1900s, except the equipment was simpler, more basic in nature. The Journal article advised: “Those who hunt ducks for pleasure have found that warmth and dryness are the most essential things in providing for the outing, and that they must wear plenty of good woolen clothing, for it is an extremely hard and uncertain sport.” One of the worse things for a hunter is getting wet and cold. The article goes on to say: “The first necessity in the garb of a hunter is plenty of heavy underwear. He should also wear thick trousers over which is drawn a pair of dead-grass canvas overalls. A heavy blue flannel shirt or sweater is necessary in protecting the chest, as is likewise a high-cut vest, preferably without sleeves.” I wonder why a “blue” flannel shirt is necessary. As a hunter, I can tell you that cold feet make any hunt miserable. The same went for the early 20th century hunter. Foot wear was the next subject in the article: “After a hunter’s body is well clothed his feet should be the next looked after because in this kind of hunting he is wading in the deep marshes frequently through all day and must be certain to keep his feet warm or he will suffer great inconvenience. To do this a pair of rubber boots reaching to the hips and about three sizes too large is necessary. The reason the boots are worn so much larger than the feet is to enable the wearer to put on two pairs of heavy woolen socks together with a pair of moccasins. A cap with a hood attached and a pair of warm gloves complete the outfit.”

Much of the research for my River Bits columns comes from historic newspapers. I am surprised by the number of mentions of finding the remains of unfortunate hunters or hunters simply not returning home from the marsh. The Indianapolis Journal’s article made clear the need for a guide for  those new to hunting the marsh. The Journal’s reporter was blessed to be directed to long time Kankakee Marsh “pusher” Sandy Sollars.

those new to hunting the marsh. The Journal’s reporter was blessed to be directed to long time Kankakee Marsh “pusher” Sandy Sollars.

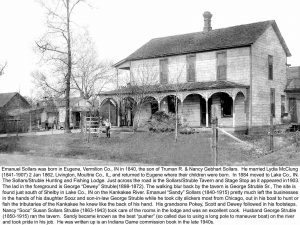

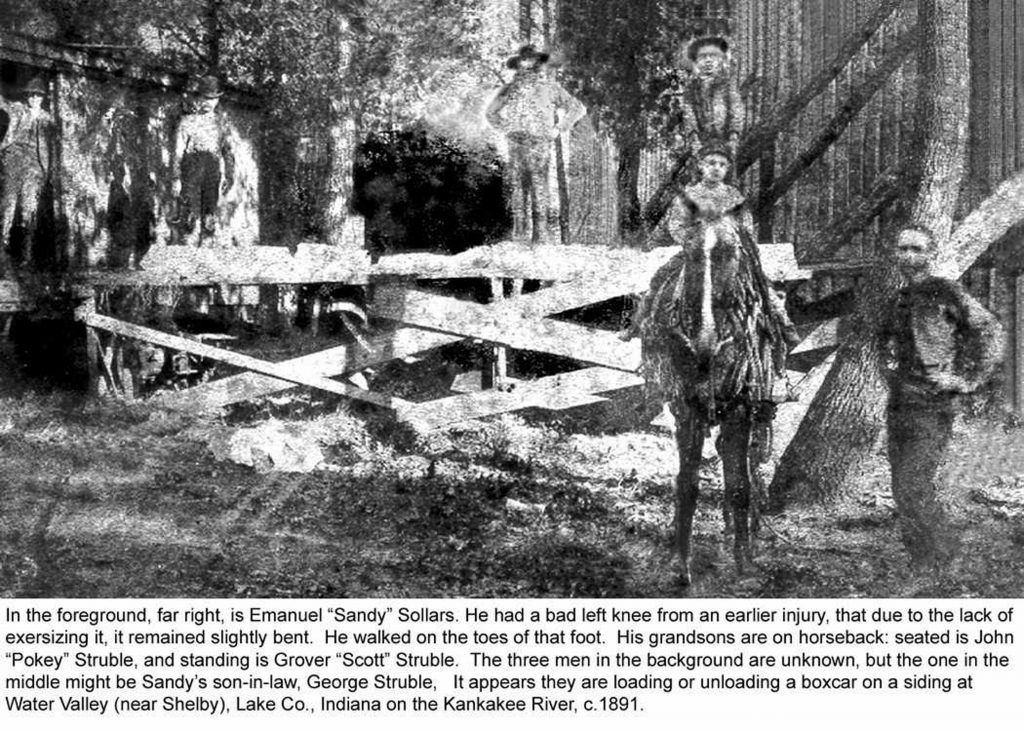

Emanuel “Sandy” Sollars was born in about 1841 in Eugene, Indiana to Truman and Nancy Gebhart Sollars. In 1862 Sandy married Lydia Amanda McLung. Sandy and Lydia had six children, but only two survived to adulthood. The Sollars moved to Water Valley in south Lake County, Indiana in the 1880s. Sandy and Lydia owned a large home which they made into a hunting lodge. Sandy also owned a tavern and stagecoach stop across the road from their lodge. It was from here that he guided the sportsmen to hunt the marsh.

Kankakee Marsh guides had varied occupations. Most farmed, trapped or timbered. Others, as market hunters, supplied the needs of Chicago shops and restaurants. Sandy was no different as reported in the Journal; “Sandy has a little farm where he raises vegetables and during the summer months he fishes extensively. Pickerel is the favorite fish around this place and is found in great abundance. In the winter Sollars hunts and traps mink, muskrat and coons… Another sport which Sandy likes exceedingly well is hunting bee trees. He is quite an expert at this and always has a large quantity of honey about the house. Whenever he sees a honey bee he can follow it through woods, and there is no getting away for the bee.”

shops and restaurants. Sandy was no different as reported in the Journal; “Sandy has a little farm where he raises vegetables and during the summer months he fishes extensively. Pickerel is the favorite fish around this place and is found in great abundance. In the winter Sollars hunts and traps mink, muskrat and coons… Another sport which Sandy likes exceedingly well is hunting bee trees. He is quite an expert at this and always has a large quantity of honey about the house. Whenever he sees a honey bee he can follow it through woods, and there is no getting away for the bee.”

Hunters on the Kankakee were fortunate to have Sandy as their guide or “pusher” as demand kept him very busy. The Journal reporter wrote: “These “pushers,” as they are called, are peculiar fellows and are generally old professional hunters. They are not overly fond of the sportsmen from the city, for they have reached the conclusion that there are few men from town who can shoot ducks. When one of these boatmen really finds a man who knows how to shoot, he takes a liking to him and the hunter will find that his sport will be greatly improved.”

Another reason for many of the waterfowl hunting fatalities was simply the physical demands of the sport. The successful hunter needs to be on the water before sunrise to be positioned when the birds lite from their overnight harbor. Many fall mornings are chilly and placing decoys can be a cold and arduous chore. All of the work has its rewards when you can call in a gaggle of mallards into your decoy spread. The Journal wrote: “Sandy is a character in every sense of the word, and knows the habits of ducks and cannot be fooled when it comes to finding them.”

The Journal also told of methods of waterfowl hunting. Most of the “pushers” supplied the use of their boats for the hunts. The Kankakee River boat was a uniquely designed craft, of a special pattern suited to the marshes, puckerbush, and other conditions encountered while duck and goose hunting along the river—most were locally built. Another method was the use of tubs. “The tubs are made of galvanized Iron. The hunter takes his tub into the marsh or flyway and sinks it level. After this it is staked down and the water bailed out. Crouching down with his head hardly above the level, and in this position he often waits for hours for the game.”

Sandy Sollars passed away on February 15, 1915 in Shelby, Indiana.