CHAPTER XIX

Down by the Riverside

By Fay Folsom Nichols

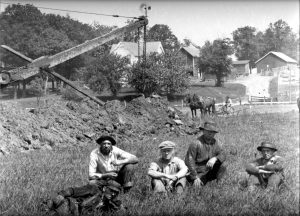

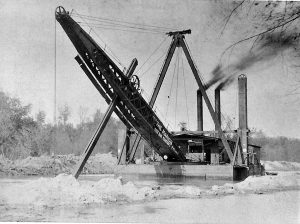

The craneman pulled on heavy leather gauntlets. Carefully he tucked a jacket sleeve inside each cuff. Then he braced himself for the first move of his machine. Cautiously he released a lever. The taut steel cable moved feelingly along its track. The long arm of the crane swung out. The first journey of its massive dipper began.

Slowly the bucket settled to the riverbed, opening its greedy jaws as it went down, to suck its first mouthful of dirt. In seeming triumph, it came to the surface. The crane swung inland, and the steel mouth spewed forth one ton of muck, slime, sand and decayed vegetation.

Anxious dredgemen watched the performance. Land speculators crowded the oozy banks in breathless excitement. The straightening of the lower Kankakee had begun. The last effort to drain up-river bottom lands, and sop up the Grand Marsh was well on its way. The year was 1917.

Perfectly timed like the bars of a great symphony, hour after hour, for long days and nights, the dredge made its way down stream. In its wake came a deep, high-banked ditch, straight and as unbending as a maypole. With reckless abandon of the river’s natural course, beautiful bends and reedy bayous were cast off like an old coat. Six thousand dollars per mile seeped out of the jack-pot.

When, at last, the machine was halted above the limestone barrier, well over half a century of drainage operations in the Valley of the Kankakee had been acknowledged, with an estimated expenditure of a million and a quarter dollars.

A deed which, thirty years later, was to bring about one of the most argumentative battles ever to have been fought, to date, within Indiana’s Senate Chamber, and leave a lasting bitterness in the hearts of many men of Northwest Indiana, had been consummated.

From this day forth the “Restoration of the Kankakee’s Grand Marsh” became an Armageddon.

The idea of draining the river’s submarginal lands probably first occurred to the early settler because of the inaccessibility of the stream itself. Only at far-distant spots, and at times of great drought or extreme cold, could the bogs and sloughs be traveled so as to reach the river.

And cutting new channels was a habit of the river. It liked to slip around a bend and scoop out an extra bayou. Hold it down to a straight and narrow stream? Never! It had plenty of tricks and played them well. Its banks were soft and oozy. It sliced off a chunk of unresting soil here; scooped out a hollow there, and first thing you knew there was a fresh bend. Then the river tipped its hat like the dandy it was, slyly winked a bad eye, and hurried away to continue the raping further down stream.

The blue jay scolding away in the top of a red maple nearest the bank knew what was in store for the limb on which he teetered. Some day it would curtsy about on top of the water. Mother roots, bereft of the soil that held the tree erect.as the Kankakee ate its greedy way around them, would give way. She would topple over into the stream. Rotting away, the log would make the perfect hideout for a nice mamma pickerel who wanted to start a family.

Finally, came the land speculator’s vision of the reclamation of thousands of acres of deep, alluvial soil, more productive than ever-soft prairie lands or barren clay hills. With his dream came argumentations and controversies carried on over a period of years, such as no other river in these United States has called forth for a like reason.

The first real drainage ditch that proved the practicality of such action was dug in 1858. There followed, intermittently, periods when there was much maneuvering of the law under a proposed drainage agenda. Petitions and remonstrances went the rounds of land owners, with plenty of signers on both papers.

The winning side was the one with the strongest lobbyists, the large land speculator and investor, trying to secure legislative action for the benefit of his thousands of acres. Never the little upland farmer. He was working on a minimum amount of ready cash. No bonds had been sold to help finance any remonstrance he might wish to make. Let him object to ditch assessments that were attached to his tax statements and objections be hanged!

Yet many a farmer living more than ten miles up from the river was assessed. If he had no more than a single tile across his land that emptied into a little natural creek, if that creek ran riverward-and most of them did-he soon learned to keep still.

The Kankakee’s swamp lands were the largest such in Indiana. By an act of Congress in 1850, the national government gave them to the state, which gift speeded up the drainage program. In 1889 the Indiana State Legislature was passing measures for the sale of lands bordering on the river. Monies thus accrued left the State treasury to pay for initial drainage operations.

“An Act,” read the measure, “to authorize the governor of the State of Indiana to apply funds derived from the sale of swamp lands located in counties bordering on the Kankakee River to the improvement of said river within the State of Indiana as an outlet for the waters tributary thereto. In force April 27, 1889.” (Burns Statutes.)

Then followed a series of such acts for the sale of meander lands to pay ditch assessments.

In their March 1 issue of 1884, newspapers of Northern Indiana had printed, “All persons interested in the subject of drainage of the marshlands of the Kankakee River are invited to meet in South Bend, Indiana, in the courthouse on Saturday, March 8. All plans will be open for consideration.”

Later, in this same year, steam dredge boats dug a series of lateral ditches, and the State put up $60,000 for the breaking through of the limestone ledge in the river above Momence, the one natural element that held the waters in two to form the Grand Marsh.

In 1900 the LaCrosse Land Company was formed. The company’s initial purchase was 7,000 acres of muck land in LaPorte and Starke counties. Practically all of it was inundated. Came the Tuesburg and McWilliams land companies; the Strauss Brothers of Chicago, purchasing the Nelson Morris’ 26,000 acres; B. F. Gifford of Kankakee City building his railroad, the Chicago and Wabash Valley, the length of the Grand Marsh, until the combined holdings of these, and several smaller concerns, were well on the way to 100,000 acres. They controlled forty miles of waterfront.

In 1902 the Kankakee Reclamation Company was formed. The object of the company being the further deepening, widening and straightening of the river from South Bend down.

There was little time left for weighing the outcome of the drainage project that was being shoved through and not enough force brought to bear on state officials for further investigation. The fate of the Kankakee was at stake, but few did anything more than talk a little. That was the early over-all picture. It was not a rosy one for anyone but the large landholder. Posterity seemed doomed to be deprived of one of its most precious heritages-the privilege to enjoy this gift of nature as had their forefathers.

Two years later there came about a grandiose scheme for canalizing the river, and probably the whole conception was no more fantastic than many another contemplated project. A communication, signed by one, F. M. Trissal, of Chicago, was sent to the United States National Waterways Commission on a proposed canal which would connect Lake Erie with Lake Michigan. It bore directly on the Commission’s Preliminary report (page 12; Document No. 301), which advocated such canal connections.

Trissal would call to the attention of the Commission the “great advantage to be gained by the selection of the Kankakee River as part of the route,” hoping they would take “judicial notice” of the location of the river.

“It will probably be intersected at some point in any proposed route from Lake Erie to Lake Michigan,” stated Mr. Trissal, “and seemingly a most direct route to it would reach it in the vicinity of its confluence with the Yellow River from whence it could be followed to its connection with the Illinois River, and thence through the Drainage Canal to Lake Michigan without greatly increasing the distance over artificial channel that might be constructed on a straight line. The expense,” the author of the proposal continued, “of straightening the channel of the River and removing obstructions from it would be much less than the cost of right-of-way and artificial channel that might be constructed on a straight line and the towns and cities that have already been built upon its banks and near it, especially South Bend, Momence, Kankakee and Wilmington are all of commercial importance and active in manufacturing enterprises.”

He further argued that the country bordering the River was peculiarly adapted for the building of such a canal because of the abundance of water that it collected. Also that this canal would become the connecting link in a general system of inland waterways, and that its improvement as such would be entirely in line with the policy adopted by the National Conservation Congress and the National Waterways Association, when in November of 1910, in a joint resolution pertaining to the Kankakee, they had declared, “We hold that each stream is essentially a unit from its source to its mouth, and that various uses of the water are interdependent, and ask provisions to be made for the complete protection of overflow lands, the drainage of swamp lands, the abatement of floods, and the control of waters in such manner as to insure the highest utility for navigation and related purposes.”

Trissal further urged that since the State of Illinois had done nothing about removing the limestone barrier above Momence, that the Indiana Legislature, under the provisions of Section Eight of Article One of the Constitution of the United States, which held that the power to regulate commerce among the states belonged to Congress, including the power to keep open .and free from obstruction, and to make such accessible from one state to the other, secure Congressional legislation on this matter. Further, he would have the Indiana legislature petition the Illinois State legislature to either make proper provisions for the removal of said barrier, or join in the call upon Congress for aid in its removal; also, for Illinois to grant either to the State of Indiana or the Government of the United States, any such rights as that state might have in the Kankakee River bed, that might be necessary to carry on river improvements.

In his petition, Mr. Trissal recommended a board of three to be appointed to examine the feasibility of such action, “that the waters of said river may become available in themselves or in connection with the Illinois River and its connected waterways, or as forming as connection with a part of a project for the construction of a large canal from Lake Erie to Lake Michigan. That said board have access to and use of such engineering data as may have been collected in the Drainage Investigation.”

Cooperation with the Chief Executives of Indiana and Illinois was recommended as was an investigation into the character and cost of the improvements, the reports to be submitted to the Board of Rivers and Harbors, and to Congress not later than the first Monday in December, 1911.

Mr. Trissal hoped his suggestions in this communication to Congress might facilitate such a “worthy project,” and bring the Kankakee and its possibility as a canal route between the two lakes, to the attention of the Commission.

It is hardly necessary to explain that the canal was never built; that such a proposition was not considered feasible, nor would any amount of commerce that might be directed this way justify the expenditure of the huge sums of money necessary to carry it forth.

But in 1947 the construction engineer who had built practically all the present-day bridges that span Indiana’s part of the river, expressed the feasibility of an express highway along the river. His idea was to run the highway directly along the bank of the river from South Bend to connect with one of the main Federal highways near the river’s mouth. Such a highway would relieve the bottleneck formed in the Calumet industrial area.

Eventually the Grand Marsh was drained dry as a leaf in the wind.

Then the fabulous old river became a hot bed of contention as sportsmen hung up their canvas hunting coats. There arose the question of a great wrong having been perpetuated. The Izaak Walton League and members of conservation clubs throughout Northwest Indiana began quietly investigating. Was it too late?

Two years before the final straightening had begun, Gene Shireman of the State Game Commission had protested against the drainage program. He tried to tell the commission it would be the final blow to a great natural game preserve.

The noise of the dredges drowned his voice. An agricultural boom was on. The ambitious land developer forgot there were thousands of acres of sandy bottom land that would forever lie barren and unproductive. They saw only the garden spots of LaPorte, Starke and jasper counties; visioned only the yield of food stuffs that would be forthcoming.

Thousands of acres which had never known the touch of the plow were furrowed and planted. Fabulous crops were the results. Comfortable homes began to pop up out of the land. The number of good roads across the river gradually increased. Better relationships between those counties bordering the river were established. Surely much good was coming out of this drainage program l

But certain forces of nature are continually at work thwarting agricultural achievements. This became particularly true in the Grand Marsh. Lateral ditches were soon weed-grown, and gradually silting up. Loose, dry sand went by way of the air route from Mr. A’s farm to Mr. B’s ranch -sometimes returning with the next change of wind. A continual movement of this sandy soil by the elements left long lines of fence posts exposed, and fencing lay on the ground, failing to serve the purpose for which it had been erected.

Only scrub oaks grew where once stood sturdy white and red oak; the glorious marsh maples, sassafras, elm and quaking aspens.

With the bends and the bayous gone, there was no place for the fish to spawn, nor for the young to hide from a greedy big brother.

Acres of wild rice, celery, duck potatoes, and other grasses and weeds that had furnished food for the migratory wildlife dried up and burned out.

Each spring and fall a mighty avian life had moved along the river destined to its breeding grounds. Unerringly the wild fowl trailed long lines of migration following beaten paths of a thousand years, giving way to inherited desires to seek nesting sites near the old home of their ancestors. True was their compass of instinct. Now the sandhill cranes, the herons, the edible water fowl continued over this Mississippi flyway without stopping enroute, or changed their course altogether.

All Northwest Indiana began reaping the harvest of its folly in the destruction of this natural wonderland through the reclamation projects-ill conceived drainage and deforestation.

During the first two hundred and fifty years of life in America, nothing was done to preserve the natural resources. There was a super-abundance of everything, particularly timber so why should anyone worry.

True John Quincy Adams became concerned over the diminishing supply of live oak timber. Steel for ship building was unknown, and therefore timber for the building of ships must be conserved. America’s sea power was important.

So as one of his first acts after becoming president, Adams withdrew thirty thousand acres of live oak on Santa Rosa Island, across the bay from Pensacola. This was our first step in forest protection.

However, when Andrew Jackson took office, his Secretary of the Navy, John Branch, discontinued the Santa Rosa project. Then followed many years of timber looting.

Forty-four years later (1873) the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a group of thinking men who realizing our forests were threatened with complete destruction had, at the instigation of Dr. Franklin B. Hough of New York, petitioned the Federal government to enact legislation that would protect our great forest areas.

In two more years the American Forestry Association had been formed. This organization set about creating an interest among United States citizens to save the trees. They were supported in their efforts by a young German emigrant, Carl Schurz. Schurz had learned the importance of conservation in his childhood days in Germany. Later, as Secretary of the Interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes, he fought for forest protection.

It remained for a son of Indiana to open the great door of Conservation. By 1890 enough interest had been created that Congress passed an act authorizing President Benjamin Harrison to withdraw large forest areas.

Harrison’s signature set aside the Sequoia National Park, the General Grant National Park, and the Yellowstone National Park. Before his term had expired, he had designated thirteen million acres of land for national parks and forests.

Since that time conservation measures have gone on apace. Now the United States Forest Service Department of Agriculture claims there are over 630,000,000 acres of forest land. Of this 196,000,000 are in public ownership-city, state and federal-and 434,000,000 privately owned.

The Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid and Wildlife Restoration Act, (50 Stat. 917; 16 U. S. C. 699-699j) approved by Franklin Delano Roosevelt on September 2, 1937, was probably the greatest of all steps taken for the protection of wildlife since the passage of the Migratory Bird treaty Act in 1918. It came about just forty-seven years to the, very month after President Harrison had signed the first conservation act.

Recognizing the fundamental principle to wildlife is inescapably linked with the land, the act, ides for the restoration of suitable environment in which wi birds and mammals may live and multiply. Since states are unable to carry out such a procedure, this places the Federal government as a necessary contributor in the wildlife restoration program.

Under the terms of the act, the United States may pay as much as seventy-five percent of the cost of the work performed on approved projects concerned with the purchase and development of lands, the restoration of natural environment, and the carrying on of research into problems of wildlife management.

Funds to carry on this work are derived from a tax placed on sporting goods and ammunition.

There are estimated to be 285 wildlife refuges, covering no less than 17,500,000 acres scattered in strategic locations all the way from Maine to California and from Alaska to the Gulf Coast region.

Indiana’s Department of Conservation was created in 1919, but it was not until eight years later that any appreciable amount of agitation was begun to restore marginal lands along the Kankakee that were proving unfit for cultivation. At that there seemed to be much talk and little action.

In 1929 E. L. Gardner of the State Conservation Department was appointed to make a preliminary survey of some twenty-five thousand acres. Nothing much came of the survey and hope again settled back into the old groove of wishful waiting.

Even when the Izaak Walton League took up the cudgel two years later, it took three years before the State Senate became interested enough to make a study of what could be done in the way of restoration without damage to tillable land that drainage had created.

Then evolved the plan to restore a relatively narrow strip along the river, plus the Beaver Lake region in Newton county. It became feasible to consider in the restoration project, three main areas: Eastern; in the vicinity of English Lake where the Yellow River joins the Kankakee in Starke county; middle; the section between English Lake and the Indiana-Illinois state line; and the Beaver Lake area. The ultimate purchase and development called for 100,000 acres of submarginal basin land.

There was much to encourage the promoters and make feasible the large scale agenda. It was the success of the Jasper-Pulaski State Game Preserve. Located just south of the river on State Highway 43, between jasper and Pulaski counties, 7,500 acres of land had been allowed to return to its natural state. Of this, 1,600 acres were natural swamp, partly inundated up to two feet of water. Here, also, was Ringneck Lake, where ducks by the thousands congregated, and were encouraged to nest. It was a habitat for other wild life. Its picnic grounds have been enjoyed since its creation by hundreds of visitors. Conservationists from far and near had been coming to study the program of pheasant propagation. It was the perfect proof that such a park could exist without damage to good farming land. Such could be a pattern of sorts for the great restoration.

Any conservation program needs heavy support. The Kankakee Restoration scenario had just such in the form of the Izaak Walton League and the state conservation clubs. Came the “do now, or die,” campaign.

In 1930 the Waltonians had first launched a restoration crusade. Results had been rather disheartening, but still there was a ray of hope. Certainly, the end would justify any amount of effort! But time seemed to have been awasting.

Then on the evening of May 22, 1946, in the Crystal Ballroom of Hotel Gary, Gary, all the pent up emotions which had been seething within the hearts of many men for the past sixteen years, burst in one great, final effort. It was a “last stand.” They set up a campanile.

Here, at a dinner meeting for over four hundred League members, conservationists and their guests, were shouldered the muskets. They were to be turned on the forthcoming state legislature. For weeks previous to this meeting agitators had stumped the counties affected, creating sentiment; renewing interest in the movement.

There was a fund of $569,000 known as the Wolf Lake Fund, lying dormant in the state treasury. It had been collected over a period of seven years by taxation of Lake county property for the improvement of the Indiana area around this lake. But the powers that be had decided the development of Wolf Lake park was not feasible. Now the Kankakee park backers sought to have the fund transferred to be used in the restoration of the Grand Marsh.

State Representative Hiestand authored the bill to convert the funds to the Kankakee when the 1947 session of the State legislature convened.

Then followed the handicap. Most of the time the Wolf Lake backers ran a little in the rear of the Kankakee agitators. For days the dust of the track almost smothered the bill. It began to look as if the money would go into the state’s general fund, and neither would benefit thereby. Finally the bill passed the House. There was still the Senate. Here the atmosphere was oppressive to the point of defeat. The bill was all but killed. Things looked discouraging. Came the bright idea of a compromise. The bill and its backers rallied.

And the General Assembly faced the problem squarely. Dodging the issue further would only prolong a dispute that had been momentarily growing more bitter. Representatives of the two factions got together. The terms of settlement came to a fifty-fifty basis. Half a loaf was better than none.

The measures were passed by the 85th General Assembly after a last minute compromise between Lake and Newton county forces. Governor Gates signed into law two bills dividing the fund between two park sites. Wolf Lake and Kankakee would share equally in the $569,000.

In addition, however, the Kankakee park was to get the receipt from one and one half mills of the State’s six and one-half mill forest tax for the next seven years. This sum, estimated at $75,000 a year would go far toward adequate restoration, since not in one year alone could the undertaking be carried out. It would be a long-term arrangement.

Too, not all of it would be needed to buy land, since several thousands of acres in the proposed area had been promised as outright gifts, and more at a low figure.

Well, it had been quite a merry-go-round ride. First the land owner had been taxed to have ditches dug, his land drained, and the river straightened. Now there would be a general exodus back to the good old days. There would be plenty of marsh for the ducks, and the “duckers,” and in tmeantime sums of money would circulate in the “ducking.”

There would be plenty of grief ahead for the “we are pledged,” fellows, but facts, logic, engineers who would share experience and technical knowledge, and new policies would be sure to carry to a grand finale a long dream. And there would be more than marsh. In keeping with the high level of other state parks, accommodations of all sorts for the vacationer and his family would go into the planning. Thenceforth would come the factory worker, the student, the housewife, the children of the Valley to revel in a great playground.

Restored marshes and submarginal lands are yearly becoming more valuable in the wild life retrieval. This is the consensus of not only the National Fish and Wildlife Service but of the American Wildlife Federation and the Waltonians. But all of them claim it is going to take the ingenuity of every state department of conservation, and every conservationist throughout the country to carry on the redress. The solution, they argue, must be deeply rooted in wildlife refuges.

Since it takes from fifty to one hundred years to produce commercial forests, the tree planting program of lumber concerns, state conservation projects, and private enterprises will be long in materializing, but men know they must go on.

The shortage of lumber in the post-war housing situation spurs conservation to a new high. Marginal land returned to cultivated forests will hold soil water, reduce erosion, clear streams; and it is claimed will put wealth back on the tax rolls.

Indiana makes young trees available to farmers who will guarantee to plant for reforestation, erosion control or windbreak.

Indiana stays in the front row. Despite its being the smallest state in area west of the Alleghenies, it places tenth in the current allocation of federal funds for the development and restoration of wildlife resources and reforestation.

The Valley of the Kankakee revels in being part of it all. Restoration of the marshlands in the very heart of the Midwest is a long-range investment in national welfare.