Oh July 4, 1800, Indiana Territory came into existence. The process had been a long and complicated one. Some historians are wont to claim that but for the bravery of Clark, the territory would still have been British property after the Revolution.

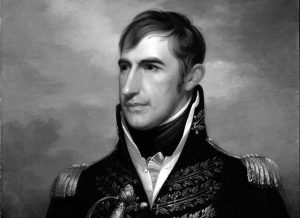

Coming from Vermont as he had, a state since 1791, traveler Washburn knew nothing of the problems or perplexities which confronted our first territorial governor, William Henry Harrison. Harrison was twenty-seven years old when he took up his duties in 1801 following his appointment the year previous.

Two problems the young governor took to heart-the condition of the Indian as the white settler shoved into his territory and the slavery situation north of the Ohio.

Harrison made the difficult trip north on horseback to negotiate with the Indians at Fort Wayne. With him were Peter Jones, his personal secretary; a valet; a French guide, and Indian interpreter and two Indian guards. Here at the Fort for fifteen days, he had worried along a treaty with the Potawatomi, the Miami and the Delaware for land above the Wabash and in the region of the Kankakee. It was wanted by the government for expansion of the white settler. Out side of a few small tracts ceded by the Treaty of Greenville, this entire area was in possession of these tribes.

New colonization was beginning in earnest. The restless settler was banging against the numerous barriers that were holding him back. Fall line, the Appalachian Mountains, the Ohio River, each in tum marked a stage in advance.

But the years were fast moving. The Northwest Territory was breaking up. Amasa set foot in the Valley of the Kankakee just fifteen years after a parcel of land containing 32,291 square miles, extending from the Ohio River north to the waters of Lake Michigan, had presented population figures of 63,897 to the United States Government and been tendered the badge of statehood (1816). It was the nineteenth state and would be forever known as Indiana. The name had been formed by adding the Latin suffix to the word Indian.

As late as the generation preceding the Civil War, observers frequently expressed the fear that Northern Indiana was lagging behind in the race to attract migrating population. Home seekers were passing over and around this area, little interested in what it had to offer. Geographic causes had been at work to repel immigration.

Colonization was visibly affected by the difference in the character of the land. There was too much marsh country down from the lake on the north, and up from the river on the south. In between there was too much prairie. The early comers were timber people, accustomed to living in timber country. In spite of the work of clearing the land, they avoided the prairies and settled in wooded areas. Men judged the soil by the trees growing there. White oak, thin soil; black walnut, red elm, rich soil though rather thin; shell bark hickory, poplars and other oaks, rich and durable.

Timber was essential. It was needed for fuel, the building of homes, for furniture and fencing. The soil, once the land was cleared, worked easily. The prairie sod turned hard. Six horses were needed for the first plowing, as the grass and roots were uncommonly tough. Few farmers had the proper equipment, and those who made it their business to “break” the land, charged five dollars per acre. And money was something few immigrants had.

Too, there was an early prejudice against the prairies. The belief was common that the supply of drinking water was not good. Those who could sought to locate near spings and small streams, but mill sites were generally lacking, and the mill must grind the wheat.

The Honorable Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, United States Commissioner of Patents (1836-1845) and an agricultural enthusiast, was a firm believer in the superiority of prairie land over timber land. He showed his confidence in the prairie soil of the Kankakee Valley by making extensive purchases of land. Beginning with his first purchase in 1835, he continued until well in the 50’s, acquiring south of the Kankakee in Benton county alone some 65,000 acres. There were others who saw a great future in land

investments. The Fletchers, bankers of Indianapolis, bought around Flint Lake in Porter county. J. F. D. Lanier of Madison, who twice placed his personal fortune at the disposal of the struggling young Hoosier state, headed a land company for the purchase of acreages in the Valley.

Men began dreaming of fortunes that would be forth coming in this great Midwest. There were:

Rings on her fingers

Bells on her toes

A poor man had a fine opportunity to place his family in better circumstances than ever before. Prairie land at $1 to $1.25 per acre, with the price reduced one-third for any poor land!

In came the New England Yankee-Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut; many who had “paused” in Ohio enroute came on seeking good corn land.

Restless, pulsating humanity. They had had no part in wresting the land. Simply they would take up as the conqueror laid down. Soon in command of the soil, their plows turned the deepest furrows, their axes sang the sharpest in fine hardwoods, they built the better houses, and opened industries that would supplement farming.