By, Richard C Schmal

The Chicago and Wabash Valley Railroad was built by Benjamin Gifford, who came to this area in 1891. He was the son of Freeman Gifford and Cornelia Fielder Gifford, natives of New Jersey, who came by covered wagon and homesteaded in Kendall County, Ill., in 1838.

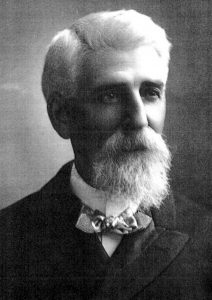

Gifford grew to manhood in those pioneer days, acquired his education, taught school, studied law, became a lawyer, and in 1861 volunteered and served under General Grant in the Union Army. During the war he was wounded several times, and carried a bullet in his spine until he died in the hospital in Rensselaer in March 1913, at the age of 73.

Benjamin Gifford acquired about 36,000 acres of the lowlands in southern Lake and Jasper counties. He drained the marshes by building many miles of dredge ditching, built public roads, dug smaller ditches, and divided his land into farms of 80, 160, and 320 acres, building sets of farm buildings on each site.

While drilling deep wells for water on his land north of Gifford, Ind., he discovered oil and built a million-dollar oil refinery in 1899.

The following story about that railroad and the enterprising Gifford is told by the “Old Timer”:

“In the summer of 1901, I had the privilege of joining an excursion on the new Chicago and Wabash Valley Railroad, a trip that offered an excellent opportunity to view the country-side and to inspect the new business venture of Mr. Gifford. Several men from Lowell took time off from their busy schedules on the morning of July 2, 1901. They were: John Lynch, J.M. Castle, A. Wilkinson, E.S. Clark, R.W. Bacon, F.E. Brownell, M. Kelsey and S.C. Dwyer. These men boarded the Kelsey Livery Bus, while Dr. Davis and Mort Gragg followed in a buggy. They were all going to visit Mr. Gifford with the purpose in mind of inviting him to bring his railroad through Lowell.

“The drive to Sheby was a splendid outing in itself, as it gave us a view of the farmlands on both sides, and there was enthusiastic comment on the great improvement on the land as we crossed the marsh to Fuller Island. We noticed the fine state of cultivation where Claude Rumsey, Lew Chapman and John Klein all had fine corn growing on the bottoms.

“South of Fuller Island, cultivation has been rapidly taking over, until there is very little marsh left. Closer to Shelby the sugar beet acreage could be seen, and the shanties and tents of the beet growers are seen in groups in every direction. We observed that the beet plants were healthier on black soil than on the sandy. “Upon arriving at Dick Fuller’s Hotel in the fast growing town of Shelby, our horses were cared for and our supper ordered for our return in the evening. We had half an hour to wait for the eastbound train on the 3-I Railroand (Indiana, Illinois & Iowa) and then sped across the river and on through the timber past Nelson Morris’ 30,000 or more acres, catching a glimpse of his herd of elk, and then on to DeMotte and Kersey, not far away.

“We were met by the train superintendent, Frank Lewis, who greeted us and invited us aboard a special coach on the train which had been waiting a half hour. Mr. Gifford, with C.C. Sigler, then came aboard to meet us and began to visit as if he had known us always. At that time he was about 60 years of age with white hair and beard. He stood erect and watched with his sharp black eyes, as he hurried among his guests, shaking his shoulders when touched with joy.

“Our course was southeasterly, with Gifford land on both sides, which was known in earlier days as the Black and Copperas Marshes. The tract embraced 33,000 acres, through which his railroad ran for 24 miles from Kersey to McCoysburg, with an outlet on the North and the Monon on the south. He had located the divide between the Kankakee and the Iroquois Rivers, dug nearly 200 miles of dredged ditches at $1,500 per mile, as well as many smaller ditches. His dream was to transform the swamps into gardens to supply the city of Chicago with fresh vegetables. The land was being farmed by his 200 tenants, who lived in good sized farmhouses and who worked under the direction of five or six foremen. His nephews, Freeman H. Gifford and Harry Gifford, were two of those foremen.

“Mr. Gifford proposed that within a year or two the breakfast tables in the metropolitan hotels would be furnished with fresh garden vegetables and relishes plucked from the old marsh lands the night before and transported over his railway.

“As we traveled along, all the land as far as we could see was under cultivation. His houses were built of timber from his own land, as well as the railroad ties. He gave every man living on the railroad land a job, and when the first year’s crops failed, he gave them employment gathering stone from off the land which they piled up at the town of Gifford.

“We were invited for dinner at the home of Mr. Henneford, a fine meal I must say. Near McCoysburg we saw the best of corn and some ‘Fourth of July Oats’ as Mr. Brownell called them.

“It rained hard on the return trip. On the way we saw piles of ties sufficient for ten miles of track planned for the line north of the Kankakee River. We talked of his route north to Lowell to Cedar Lake to West Creek, or perhaps on to Chicago Heights. Some thought that the farmers at West Creek didn’t want to sacrifice valuable bottomland for a railroad. The men from Lowell seemed to urge Mr. Gifford to come closer to their town. On our return trip we were also escorted to one of the many flowing oil wells at Kersey, met Mr. Hubbard, the storekeeper there, and then traveled to Shelby, where we said goodbye to Mr. Gifford. We promised him a rousing good time and all kinds of encouragement if he came to visit Lowell, which we hoped he would at a later date.”

Soon after the trip taken by the “Old Timer” and his friends, there was an article in the local paper telling about the new plans for the Gifford Line. Gifford drove over from DeMotte on a Friday evening, July, 1901, and called upon several public spirited land owners, many of whom granted the right-of-way through their farms. These landowners were George Norton, Thomas Craft, F.E. Brownell and William and John Buckley, Sr. The news item noted that Gifford was receiving the hearty cooperation of the majority of locals. Benjamin J. Gifford began his survey of what was known as “The One-Man Railroad” in August 1898, furnished all the money, and controlled the railroad officially known as the Chicago & Wabash Valley Railroad. That same year, 20 miles of track were completed, starting at Zodac, first to the southeast, then to the northwest into Lake County to a point east of Lowell. Then called the Dinwiddie Station, it is now the intersection of I-65 and State Rd. 2. A spur was also built to the oil refinery at Gifford, with a total forty miles of track.

Soon after acquiring engines and rolling stock, he operated two to three daily trips, with Kersey, Ind., as the head-quarters. The line served the adjoining land for many years, but after Gifford’s death in 1913, it was sold to the Monon Railroad Co.

His ultimate aim was to build his railroad into Gary, but he died before this dream was realized, and the line was never completed north of Dinwiddie Station. The right-of-way, however, was graded to a point south and east of Crown Point.

In September 1935 the Monon Co. was given permission by Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon the Gifford Line.

The loss of this railroad caused great inconvenience to the area, especially the eventual loss of two grain elevators east of Lowell, the Lowell Grain Co. at Dinwiddie and the other owned by O.G. Fifield on Range Line Rd.

Benjamin Gifford’s dream of getting his railroad to Chicago almost came true.