by Dr. F. E. LING

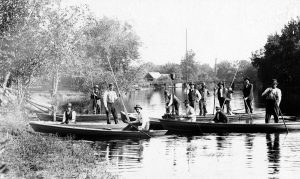

I sat in the stern of the boat, flat on the bottom, and by using a short paddle tried to keep the boat about a certain distance from the hank as we floated downstream. Using an eighteen- to twenty-two-foot- cane or bamboo pole and about the same length of line with a Skinner or Chapman spoon, Father would throw out toward the bank under the overhanging branches of trees or along the logs, grass or moss, and draw the spoon around in front of the boat. When he hooked a large pickerel, walleye, bass or dogfish (grinnel) the fun was on. As I grew older I learned to stand up in a boat and push or fish. Later he built me a boat of my own, and then a chum and I spent most of the summer days on the river.

My first acquaintance with the Old Kankakee was about fifty years ago when I was youngster six or seven years old. My father, who owned a store here at that time, enjoyed hunting and fishing and took me with him. We would leave home early Sunday morning and walk about four miles to the boat landing at the edge of the marsh, aiming to get there about daybreak and out to the river by sun-up.

We never put “if” in the fish-catching game. It was a mighty rare occasion that we didn’t get all the fish we wanted. We seldom looked for bait until we got to the river. You could catch frogs, minnows, crayfish or hoppers there. We caught our minnows by hooking the knob end of the push paddle into the moss and pulling it out on the bank and picking the minnows out of the moss, or by running the boat along about five or six feet from the bank where there was moss, stepping on the edge of the boat and holding it as low as we could without dipping in any water. Then we would hit the moss with the paddle and the minnows in their fright and haste to get away would jump into the boat.

This will give you some idea of why the Kankakee had fish in it. It had ideal natural spawning and rearing conditions for fish. One season the river was alive with small pickerel weighing about a pound and a half. A boy friend and I caught eighty-seven in about an hour. He caught thirteen fish in thirteen straight casts of about thirty feet. On the fourteenth cast he hooked a fish and lost it. He threw his steel casting rod down in the boat and said, “Damned if this is fishing. It’s slaughter.” Then he lit up his pipe and enjoyed himself.

You could catch these fish anywhere for miles along the river. Where they came from no one knew. One other year we had a similar condition, but not so many fish, but larger ones ranging from four to five pounds. They must have had the natural feed all eaten, for they would hit anything that moved. Father and I caught fourteen in less than a mile of river. On one cast, when one hit his spoon, it jerked the end of the long cane pole into the water and another fish struck the end of the pole, the splash having attracted it. These years were the exceptions, not the rule, but we always had lots of fish. Many times when we were kids have the kid brother and I dragged a string of fish on a dog chain, which was too heavy for us to carry, from the boat landing to where the old cranky wagon and pony were left on high ground. Many and many a time have I looked over the edge of the boat and seen a school of bass or wall-eve in ten feet of water. The water was very clear and there was no pollution before dredging. It is not so clear since dredging, but has no pollution even now.

In the spring of the year, after the ice had gone out and we had had our first thunderstorm, the old fishermen would go dogfish spearing. They would anchor their boats on the shallow side of the river bend on a sand bar where the water was from four to eight feet deep and where the current would carry the fish over the sand. The fish would come lazily floating down, resembling sticks of sunken wood. They would come drifting along from singles to droves of six or eight and the fishermen would spear boatloads of these fish and salt them down.

The dogfish run was on every year as far back as any of the old timers could remember, and the Indians before them enjoyed the same sport. When they dredged the river the run stopped and there are very few in the ditch now. The dogfish spearing started the season’s fishing and it wound up with walleye fishing late in the fall when slush ice was running in the river. Live minnows were used for bait at this time of the year and the fishing was done just on the lower side of a drift, the drift of logs protecting you from the floating ice. We had several varieties of fish: dog, cat, bullheads, carp, buffalo, pickerel, croppies, bluegills, perch, suckers, sunfish, black bass, wall-eyes and some eels. Many a day have we filled a stringer with a catch of different varieties.

The swamp and marsh ranged from one-half to five miles wide and was about one hundred miles long. This expanse of territory with its sloughs, bayous, ponds, natural feed and hollow trees made it a wildlife haven. Very many kinds of trees, shrubs, flowers, grasses and aquatic plants grew in this area. Many of the bayous and pond holes in the timber and marsh were a white carpet of water lilies and the banks of the bayous and ponds were lined with marsh hollyhocks. In our upland gardens they are called hibiscus. In the spring the islands were one mass of flowers-spring beauties, Dutchman’s breeches and violets. Later the May apple covered large areas with its umbrella foliage and the Indian turnip with its green calla lily bloom was seen everywhere. Squirrels, groundhogs, chipmunks, flying squirrels and many varieties of birds were numerous.

The greatest thrill of a squirrel hunt was that the whole area seemed to be alive with wild creatures. Many a time have I sat at the base of a big beech tree by the hour watching the wild life and not firing a shot. This area of from ten to fifteen acres seemed to be completely roofed over by the spreading tops and branches of the big beeches. I haven’t words to describe what took place in this apartment building of Mother Nature’s. When the squirrels were working on the beechnuts, the dropping of shells and nuts sounded like heavy rain. A hunter killed a mixed bag of 103 black, gray and fox squirrels in this area in one day.

The trees on the islands were beech, white oak, burr oak, red oak, black oak, hickory, pepperage, butternut, black walnut, white ash, black ash, sycamore, soft maple, sassafras, wild cherry and paw-paw. On the low lands there were pin oak, burr oak, black oak, red birch, elm, black ash, white ash, sycamore, cottonwood, soft maple, quaking aspen and willow. Acres of witch hazel, blackberries, raspberries, blueberries, huckleberries and wild strawberries were, found on the islands and around the edge of the marsh. Large areas of pucker brush and devil pins were found in the lower areas around the bayous and ponds. In the marsh wild rice, smart weed, Spanish needle, celery, duck potato and many other grasses and weed seeds furnished natural feed for geese, ducks, birds and animals. In the timber they found acorns, wild rice, smartweed seed, pucker brush halls and other aquatic plants and roots.

During the migration season ducks, geese, brant and cranes were on the Kankakee area by the thousands and there were all varieties, from canvas backs to fish ducks. Canada geese fed on the prairie in the wheat and cornfields and rested on the marsh by the thousands. The tales some of the old timers tell are almost unbelievable. Sandhill cranes were plentiful but not nearly as numerous as geese. Many swans were seen on the marshes. Later in the season hundreds of herons, blue and white, nested here. At different places in the swamp the cranes had what we called “crane towns.” Hundreds of them would meet in one locality in the cotton-wood trees. Many times I have seen as many as four or five nests in one tree. The largest town, the one we called “lower crane town,” was estimated to have 1,000 cranes and, believe me, there was some music when the young were in the nests ! Thousands of jack snipe, sand snipe, plover and other shore birds lined the marsh shores and upland ponds.

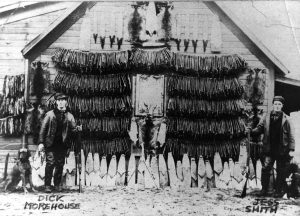

The principal fur bearing animals were muskrat, mink, otter, skunk, racoon, fox and beaver in early days, and occasionally a lynx and bobcat. In 1912 on the Degolia marsh, a tract of from 1,000 to 1,200 acres, from November 1 to December 20, the date when the marsh froze over, two trappers camping together caught 7,634 muskrats. During a period of a few days after the freeze-up they speared 1,300 more in their houses on the same grounds. This was a good rat marsh but not any exception to many others along the Kankakee. In the winter when the swamp was frozen over, fur was hunted on the ice. The party generally consisted of two men and three or four dogs. Two men could work to better advantage than one in climbing trees and throwing out the ‘coon and chopping mink out of their dens. It was not uncommon for a pair of hunters to catch from $500 to $1,000 worth of fur during the ice hunting season. This was a free-for-all, the old trappers holding their trapping grounds by what they called trappers’ rights, but the rights ceased when the swamp froze up.

The swamp had many hollow trees and many of these held swarms of bees. I have known one man to find sixty-five bee trees in one fall. Twenty to thirty-five bee trees were just an ordinary cutting. I have seen them produce honey in amounts all the way from the size of a walnut to two washtubs full. You never could tell from the looks of a tree what you were going to find. Sometimes when you had washtubs and boilers ready, you needed a hot biscuit, and other times you had to leave part of the honey or make another trip for it. In the winter many of the natives for miles each side of the swamp cut the timber for fence rails and wood. In the late afternoon and evening the roads leading from the swamp would be a procession of loads of wood. Timber, fur, fish, birds, animals and game weren’t all there was to the Kankakee. It was a beautiful, clear, winding river with its tree-covered banks, its large drifts of logs, wild hollyhock banks and lily-covered bayous.

In the fall it presented a beautiful scene with the foliage flaunting all the autumn hues, ranging from the deep green of the pin oak to the naked branches of the ash, and every bend offering a different picture. The time I liked most to be in the swamp was when the leaves were all off, the wind blowing a gale, lashing the tops and limbs of the trees, a gray, drab, fast-moving clouded sky, and the air full of ducks trying to find a shelter from the coming storm. This kind of a scene meant you were going to have a hard push home in a storm, but it was worth it.

The Kankakee was one of the greatest wood duck nesting grounds in the U. S. A. Hundreds of pairs nested yearly in its hollow trees and stumps along the river, bayous and ponds. During the summer months, before the young were able to fly any distance, the broods were scattered all over the river and swamp wherever there was water and feed. You would see many broods of them in the summer while fishing. In August when the young were able to fly they began to congregate in certain roosting places. For about two hours before dark in certain areas of bayous, ponds or sloughs that had lots of old logs, floating flag roots and pucker brush, the air was full of wood ducks, from singles to flocks of fifty coming to roost. It was not uncommon to see 500 wood ducks in the air at one time, in these areas. They fed all over the swamp and sloughs, mostly on acorns from the thousands of trees in the swamp, but they roosted in certain suitable areas as soon as the young were able to fly well. The destruction of such good nesting and rearing areas has had much to do with the scarcity of wood ducks. I believe that drainage has done more to create our scarcity of ducks here than all other causes combined. Thousands of ducks and many geese nested here before the area was drained.

One late fall afternoon when no birds but the red headed woodpecker were stirring, a slight northwest breeze had just started to blow as I was leisurely pushing my boat up the river, aiming to get to the boat landing at dusk, having agreed to meet my hunting partner there at that time. I was about a mile from the landing when I heard someone call to me to hurry up and get to the landing as soon as I could. I looked around and saw my partner pushing as fast as he could and motioning for me to hurry on. At that time I also saw several flocks of ducks coming from the southeast, going northwest, and bent on going on about their business and paying no attention to a call. He called to me again to hurry on to the landing and waste no time. I knew he had some good reason for wanting me to hurry so I put on all steam ahead, and when I turned in at the ditch that led to the landing and boathouse I slowed down and waited for him to catch up.

By this time the air was full of ducks, all going northwest, but they paid no attention to the call, not one of them. When he ran his boat alongside of mine he said, “Hurry up, let’s get to the landing and try to kill some of those ducks.” We grabbed our guns, hunting coats and shells and ran about ten rods to the top of the ridge, which was maybe forty-five feet above the water. DIy partner said the ducks were changing marshes. They had been up east in the south marsh and were going to the north marsh. These marshes were so called from their position to the river. He said that tomorrow we could go back in the territory we had been in today and found no ducks, and find plenty of them, for they were moving in.

When we got to the top of the ridge his instructions were, when a flock came over us within range, to pick out a certain bird, follow it until it was directly overhead, jump in ahead of it, shoot one shot only, and we would kill some ducks. Did lie know his duck shooting? I’ll say he did!

We picked up a mixed bag of sixty-eight ducks in about an hour out of this flight and they were flying just as thick when we quit shooting as they were when we began. Then the weather man decided we had enough and sent a northwest wind with heavy, thick, dark clouds, which made it rather uncertain shooting. Rather than cripple and lose the ducks we unloaded the guns.

My partner was one of the old time real hunters. He studied and understood the habits of birds and animals. He wanted to know why they did this, and why they did that, and lie figured out many of the whys. It was the rule rather than the exception for him to kill two ducks at one shot on the wing when coming in to decoys. He said that a pair or more of ducks very seldom came in to decoys without two of them crossing within gun range.

Before the drainage of the Kankakee we had hundreds of prairie chickens and many partridges. Now we haven’t any. Their natural home has been ruined. In destroying the native marsh grass they destroyed the home for the chicken, it being their nesting place. It seems that certain conditions and feeds are essential for the nesting and rearing of wild birds and animals. Nature provided this, but the progressive, intelligent white man in his march of progress has failed to consider this and consequently unless there is a change of policy our wild life must go in spite of its efforts to continue with us.

Some spots of this drained land are still producing fair crops, but the part we wish to restore is practically worthless and could be made a wildlife haven by reclaiming it according to the State Conservation Department’s plan. Not only would it be a wildlife haven, but a source of much revenue. Its location is ideal for recreation, having several million people within a hundred mile radius. I hope to see the circle completed-from marsh to wilderness and back to the original wonderful marsh again.