In 1822 a group of Mackinac boats landed a Frenchman and his family, together with all their belongings and French and Indian servants on the shores of Lake Michigan in what is now Porter county. The boats were strange looking craft, about thirty feet long, having in the center a framework of slight posts supporting a cover of canvas with curtains at the sides that could be raised or lowered as the passengers pleased. Sturdy oarsmen were at the paddles. Moving along from river mouth to river mouth, following the scallops of the shoreline their boats grated upon the hard packed beach as if chanting, “journey’s end.”

The lake had been high for several days. Traveling had not been too sure. Only the skill of the boatmen had prevented certain disaster. But now, in the cool of the summer’s evening, there was calm. It was good to have one’s feet again upon the ground. Soon kettles were boiling. The odor of venison stew, broiled fish and freshly baked com cakes drew all hands about the campfire.

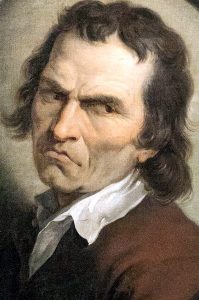

Joseph Bailly de Messein, French trader and fur buyer, had come to establish a trading post at an unsettled spot in what he thought to be Michigan Territory. With him were his wife, Madame Marie Bailly, their daughters, Esther, Rose, Eleanor, and son, Robert, and the family servants.

Eight years before, Bailly had been arrested, falsely, by United States officers as a spy. He had spent the winter in prison, while Madame Bailly, in the care of faithful John Baptiste Clutier, had undergone a dangerous and almost unendurable journey back to relatives and friends in the Mackinac region. Bailly had come out of prison broken in health and with small means. Marie had given birth to a son, who died shortly after; her own life had hung by a thread for days.

The fur trade had been suffering from the invasion on the frontier by the British and the War of 1812. Bailly was just beginning to regain his old spirit and self-confidence. Now he walked about without fear. The redmen knew him as a friend. Safety and a warm welcome were before him. Active years in the fur trade, most of them filled with daring and hardships, were behind him. He was no longer a young man, but he sought to establish a home, bring religion to the Indian and increase his business in a hitherto unsettled area. Marie had regained her health, and a son, Robert, had been born to them.

Secure in an inner pocket of his jacket the trader carried a paper. An official document. It guaranteed his safety so far as the United States government was concerned. It had been issued to him as he was released from prison. He also carried a license from Governor Harrison, issued in 1814, as head fur-trader of the Calumet Region.

Ten years had passed since Captain William Wells had fallen, an Indian arrow piercing his heart as he valiantly fought to protect that little company of men, women and children, tricked into leaving Fort Dearborn, to march through the dune country, most of them meeting death before they reached it. In that time Captain Hezekiah Bradley and his soldiers had rebuilt the fort. John Kinzie, “Silverman,” had reopened his trading post there. Jean B. Beaubien and Francis LaFrambois had established themselves at the mouth of the Chicago River.

Bailly was no stranger to this area. He had dealt with Alexander Robinson, half-breed and Astor agent established at near-by Petit Fort (Little Fort), since 1796. Without doubt the Frenchman, together with Madame Bailly and their Indian guides, had traveled overland along this coast numbers of times enroute from their post at Pare aux Vaches to Fort Dearborn.

It was the beauty of the region that had drawn them to his particular spot. And its security.

It was the strategic location where trappers enroute to and from Fort Malden, Canada, Quebec and Mackinac could be intercepted for blankets, knives, guns, trinkets and rum!

Back a distance from the lake, on a knoll overlooking he Calumet from the north, the trader erected a group of buildings and established his trading post. Tall colonnades of magnificent hardwoods secured privacy and seclusion from Lake Michigan gales.

Time and history never will unfold all the old Indian trails that were a network through this area. But Bailly’s post was on the Old Sauk Trail over which Indians passed yearly with peltries worth a king’s ransom; a post which rivaled the St. Joseph-Kankakee portage with the redmen from the entire southern portion of our country.

The priests, among them the Bishop of Vincennes, Maurice D’ Aussac De St. Palais, enroute to and from Detroit, stopped at the Homestead. It was their first charge after leaving Bourbonnais on the Kankakee.

The shape of things to come change almost unknowingly. Subtle was the entrance of the Bailly family into a new age. The sands of the dunes had absorbed Pokagon’s tears. The Potawatomi, the Sauk, the Fox and the Miami no longer passed down the Old Sauk Trail. The Isaac Morgans; the Furness family had set their plows in Porter county soil to become respected neighbors.

The French trader’s livre (ledger) showing that pelletries (peltries) were debited during the months of June, July and August to the amount of 99,723 pounds, thus aggregating nearly a half million dollars, was closed. The trading posts he had established on the Grand River, at Pare aux Vaches on the St. Joseph, down the Wabash, along the Kankakee and south as far as Baton Rouge, were dismantled. No longer would he be writing of transactions at such places designated in his index as “Venture a la Grande Rivier “A Venture a la St. Joseph,” “Venture a la Kikalimax,” “A Venture a la Wabash,” “Livre pour les affaires du Pa re a Vaches Lo 2 Aoust.”

Now he was platting a town-“Town of Bailly, Joseph Bailly, Proprietor, Dec. 14, 1833.” He laid it out “four-square.” He honored his family in naming the streets. Avenues bore the names of the Great Lakes. It appears from his papers that one Daniel G. Gurnsey was acting as his agent.

But the health of the sturdy old trader was beginning to fail. His prescient intellect turned his steps.

Too often he recalled that August Sunday afternoon in 1826, when the daughter Lucille and the son Robert, whom he loved so well, were playing at fencing, Lucille with Robert’s steel sword-his own present to the boy-and Robert with a stick. Seeing again that red blood oozing from the boy’s breast where the small sword had pierced it.

Too often he remembered the last rites-the Protestant services read by his trusted friend, the Rev. Isaac McCoy; and those indelible words of Chief Pokagon, spoken first in the tongue of the Algonquin, then in English:

Men of Prayer, I beg of you to let me speak for myself and for my lndian Brothers, of the little boy Robert, the little Bird Boy, son of the Wing Woman, son of the Lily of the Lake, whom we all loved, let me speak before you put the sand over his little body. He was the finest little boy we have ever seen among the red or the pale faces. He was as quick as a deer, as strong as a panther, and as graceful as a seagull on the shores of Lake Michigan. The birds and animals loved him. The Indians loved him. The Great Spirit, whom the pale faces call God, has touched him, as the Great Spirit has Touched his father, (Monami) Joseph Bailly and his mother, Marie Bailly, the Lily of the Lake. He was never known to do a treacherous thing, yet he was strong as a boy should be. He would have been a great man in the land of the living. He will be a great man in the land beyond the grave. He has gone ahead of us along the great White Way of the stars, to the Happy Hunting Ground beyond. The Spirits there will love him as we have loved him here. 0 Great Spirit, 0 God of the palefaces, be kind to the bird boy.”

Instead of urging land sales, he prepared his estate for administration by other hands. Thus Joseph Bailly de Messein left the home which he had built “to the honor and glory of God, for the traveler, and for the salvation of souls.” His children-five sons by a first marriage, his four daughters and a son by Madame Marie Bailly, had received educations comparable with the best of the times. Robert, the son of Marie, a boy in whom both parents had placed such hopes, was buried in the family plot on the estate. But his daughters, reared in the strict French Catholic faith, together with the beloved Marie, his Lily-of-the-Lakes, would carry on.

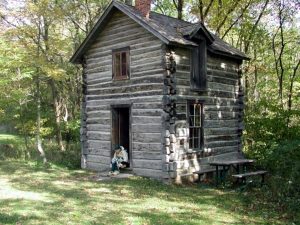

One doesn’t crowd several life-times into a few pages. But even today you may drive a short distance down a side road leading off Indiana State Highway 20, cross a sturdy little bridge that spans the Calumet and see, rising sharply up a drive on the right, the old Bailly Homestead. Here, upon a knoll among the hardwoods, breathing fantastic once upon-a-time stories, is the imposing home built by Joseph Bailly, the first white man to bring his family and make permanent settlement in Porter county. On a foundation of enduring Quebec stone, it rises, magnificently, to look down the river. Its walls, built of heavy timbers, sheathed and sided, are said to be 18 inches thick.

The house is set into the hill in much the manner of a bank barn. The original front entrance was on the river side of the house on a level with the ground. Up a narrow winding staircase which leads to the old family dining room, one passes at the head of the stairs a beautiful stained-glass window. Its center pane is of frosted glass depicting a pastoral scene. Here, still, the sun, from mid-morning until late afternoon, floods with pastel shadows this lovely walnut paneled room. Dominating the room is the imposing hand-carved walnut mantel. It reaches from floor to ceiling. Its wheat and grape carvings bespeak the Last Supper. This, together with the lithograph of the Bishop of Vincennes, Maurice IY Aussac De St. Palais, set in the center of the upper portion, breathes the true, unswerving faith of the entire Bailly family.

Wood trim throughout the house is of walnut and cherry. Floors are parquetry. The original hardware is handwrought. Grouped about the dwelling in plantation manner are the old chapel, block house and trading post. All are of gray, weather-beaten logs, these buildings remaining from the eight log houses originally erected for French retainers, Indian traders, and as storerooms.

Over it all is a feeling that a secret door will slide open and Joseph and Madame Marie Bailly will walk down the steps to graciously welcome the Isaac McCoys, Baptist missionaries enroute from their mission at Carey to Kansas with the Potawatomi; the Kinzies and the Whistlers just arriving from Fort Dearborn for a week-end visit; or Black Hawk and his braves on their way to Detroit.

We drive north to the lake. There on the beach we envision a sturdy old French gentleman, directing the loading of thousands of peltries in his sloop and Mackinac boats for the long hazardous trip to Mackinac. We hear the big, booming voice which carries the laughter of jovial Joseph Bailly, as he gives a French retainer a friendly slap on the back.

We share his dreams of a harbor where would anchor ships flying the flags and bearing the commerce of all the maritime nations. We listen to Daniel Webster, speaking here to a crowd of people, interested in Bailly’s proposed harbor, with his promise to return to Washington to present the matter to Congress.

The story of the Bailly family following the father’s death, the history of the Homestead after it left the hands of Miss Frances Howe, a granddaughter, is quite another story. Briefly it was owned by the Sisters of Notre Dame, who, after using it as a retreat for a number of years, sold it to Joseph LaRoche, a Chesterton contractor. Just why the Homestead and its eighty remaining acres were not purchased by the State to be included in the Dunes holdings, or by the County Historical Association, is a moot question. Surely this historical center of Northwest Indiana is worth considering.