They Say the Kankakee Is Coming Back

Indiana Has a Practical Plan for Restoring a Hundred Thousand Acres of Famous Marshland to a Wildlife Paradise

By William Bridges

There never was anything quite like the old Kankakee marsh in northwestern Indiana the Grand Marsh they called it in its great days sixty years ago. Never anything else and never will be.

The superabundance of its feathered game and fur and fish was next to unbelievable. I have heard old men recall the mighty rush of wings as clouds of ducks rose before the guns of the market hunters, listened to their description of creaking wagons hauling hundred-pound bales of mink and otter and ‘coon and muskrat skin into the railroad towns, and pictured through their memory the flat-bottom boats that sometimes sank under loads of bass and perch and pickerel.

As a child I remember the soft spring nights and the frosty October evenings when we strained to follow the faint music of migrating geese, wondering the while if they would again nest in the Kankakee and find food there another autumn.

Last summer I went back to the Kankakee. I had never actually visited that section of my native State before, but the Kankakee—the Grand Marsh—-was as real to me as the memory of things seen. I knew in general what had happened there in the last thirty or forty years. Land promotion schemes had flourished as it was ditched, drained and turned over to agriculture; railroads into Chicago crisscrossed it; the prolific wildlife had vanished. The old Kankakee marsh was drained and ploughed out of existence, but there was talk of its restoration. Somebody said that the Indiana Department of Conservation had developed a practical plan for returning a part of it to its original condition. I wanted to see for myself if it could be true, if there was any possibility of the Kankakee coming back.

Whether it is actually coming back, I don’t know. That seems to be a matter that the Federal authorities at Washington will determine the—Bureau of Biological Survey is said to be interested. But after tramping and wading and driving through seventy-five miles of the old marsh country I am convinced that the Kankakee can come back and again be the greatest wildlife refuge in North America.

Potentially the old Grand Marsh is still there, patiently awaiting the day of restoration. Sooner or later Nature is going to win, aided by ditch assessments and delinquent taxes. Then a thousand weed-grown ditches are going to silt up permanently. Spring thaws and the rains again will flood the lowlands that were never intended for anything but a wildlife paradise.

I saw a thousand acres of the old marsh living again. It was a private restoration undertaken by one large landowner who had grasped the vision and led the way in showing what can and eventually will be done. Old timers in the Kankakee told me that here the waters again are teeming with fish, that sprouting sedge and wild rice again draw the wild ducks. More important, from an engineering standpoint, the Cameron development stays flooded the year around without affecting the drainage of the higher land that has been reclaimed successfully for agriculture.

When LaSalle discovered the Kankakee in 1679 at its source near South Bend, Indiana, it was perfectly described by its Indian name: “Slow river flowing through a wide marsh.” For a hundred and fifty miles across the northwestern corner of Indiana it turned and twisted before it joined the Des Plaines River, becoming the Illinois River and one of the tributaries of the Mississippi.

The “wide marsh” that the Indians knew bordered the uncertain banks of the Kankakee and extended back from one to fourteen miles. There were really two sections of the marsh: the “lower marsh” or Grand Marsh of about 400,000 acres which remained flooded throughout the year, and the “upper marsh” of some 600,000 acres that was usually but not permanently flooded. Together, a million acres of fish and wildlife paradise.

Hunters and trappers came in the footsteps of LaSalle and his voyageurs. For a hundred and fifty years they did their best to exhaust the inexhaustible reservoir of fur. Market hunters poled their way into the swamp with barrels of gunpowder and shot, shipping trainloads of wild ducks and geese into Chicago. The advancing tide of pioneer settlement reached the Kankakee valley and the timber was cleared from the higher ground, but until about 1860 the lower and upper marshes were still untouched and for a long time after that date the inroads of drainage and agriculture were gradual.

The great days of hunting in the Kankakee were roughly between 1850 and 1890 when sportsmen’s clubs sprang up everywhere in the Grand Marsh-the Alpine, the Marion, the Prairie, the Valley, the Diana, the Wallace and so on. The Wallace, incidentally, was named for General Lew Wallace who wrote most of “Ben Hur” on his houseboat there. The wreckage of the boat still can be seen against the crumbling bank of the old river bed at Baum’s Bridge.

English Lake, Thayer, “Wilder’s, Baum’s Bridge were some of the great names in those days. The Kankakee’s fame was international and hunting parties of the English nobility used to shoot at Cumberland Lodge near the Illinois line.

But agriculture was creeping in. As early as 1873 they began cutting drainage ditches through the Beaver Lake district and as the higher and naturally drained land on the outer fringe of the valley was preempted, the rich muck of the lowlands attracted speculators.

At first the drainage ditches were turned into the tortuous old river channel, but the runoff was not rapid enough. It soon became apparent that the channel itself would have to be straightened and deepened to secure faster drainage. Finally, a new seven-mile channel was cut for the river, thereby draining about eight thousand acres.

What happened was about what might be expected. More water flooded down from the head of the river and made flood conditions worse in the lowlands. Speculators saw the possibilities of a straightened channel that would drain the entire valley and they pushed it through. A State drainage law was passed to speed up the wreckage of the old marsh and in the space of a few years 87.8 miles of arrow-straight new channel had been cut through the valley and narrow drainage ditches dug to carry the marsh water to it. When they finished the last of these lateral ditches at the Indiana-Illinois State line in 1917, the project had cost a million and a quarter dollars and the real costs were just starting.

It was advertised by the promoters as “The richest farmland in the world” and excursion trains were run into the Kankakee country from all over the Middle West. The intricate system of drainage ditches was to avert a return of the floodwaters-and they did as long as the ditches were new and clean. But the loose, sandy soil washed easily and the drainage ditches began to fill up along with the new river channel. Dredging assessments piled up and in some sections crops would not thrive.

Today thousands of acres of the old Grand Marsh have been abandoned and I traveled for mile after mile over sandy trails in a wilderness of weeds and scrubby trees, occasionally crossing a choked-up ditch with its pool of stagnant water. Of course, there are other thousands of acres of the former marsh under cultivation and producing profitable crops, just as fine an agricultural section as one could desire, but this area is not affected by the restoration plans.

There are about three-fourths of the former Grand Marsh which are dry, high and really profitable for agriculture since reclamation but it is with the remaining, definitely sub-marginal, acres that the Department of Conservation and the Bureau of Biological Survey are concerned.

Department of Conservation engineers made a preliminary examination of the Kankakee Valley in the fall of 1933 and went back in December of that year to start on a topographical survey of the area from the Indiana-Illinois line up the river to the English Lake district, covering a strip about ten miles wide and fifty miles long. They came out of it well informed as to the extent and value of the sub-marginal land, the location of areas that might be restored without affecting the drainage of higher areas and with suggestions for economical restoration.

This survey, I was told, was almost diametrically opposed to the surveys which had been made in previous years, so far as the protection of agricultural interests was concerned. Restoration heretofore was considered more from a standpoint of restoring the river to something like its original condition, with the resulting marsh along its entire course. The idea presented in the 1934 report was for the restoration of certain favorable areas without affecting the river itself. Such a plan naturally does not affect the drainage of the Kankakee valley as a whole and makes certain the adequate protection of the drainage for bordering agricultural lands. The restoration methods proposed in this survey report, I learned, have been approved by a nationally-recognized authority on drainage who agrees to the practical value of the plan and the non-interference with existing drainage from the agricultural areas.

Indiana conservationists are pinning their hopes upon the Federal government for this partial restoration program, feeling that what might have been an impossible task for the State is really a modest one under the national policy for the acquisition of sub-marginal lands. They realize that the land prices might be higher than are customarily paid for wildlife restoration, because of the location of the areas, but point out that this same location is one of the factors making it more desirable.

The areas proposed for restoration are situated between the existing duck flights along the Illinois River and Lake St. Clair. There is no doubt that if the partial restoration is effected, the duck flight would come to this region in increasing numbers. The major reason, however, for favorable consideration, is its accessibility (it would be within an hour’s drive for ten million people) and the large number of people who could see and become familiar with the activities of the Bureau of Biological Survey. To me it seems that the plan is good not only from a practical standpoint but would be of value in selling the Biological Survey’s program generally.

The report of the engineers after the 1934 survey recommended the acquisition of approximately 100,000 acres, or one-fourth of the old Grand Marsh. This was roughly divided into four areas: 1. The lower river valley extending from the Indiana-Illinois line; 2. The Beave Lake area which was not originally a part of the Kankakee Valley but was the feeding ground of many migratory birds and inhabited by fur-bearing animals; 3. The Jasper County area; 4. The English Lake district.

During my trip we visited each of these areas and it seemed that the Beaver Lake and Jasper County areas were entitled to first consideration, an opinion in which the engineers concurred. The Beaver Lake area proposed for restoration would include about 36,000 acres, roughly bordered by the State line and three State highways (l0, 55 and 14). Most of this area is flat, surrounded by ridges and higher ground which made it a natural reservoir, varying from marsh near the rim to a shallow lake in the center. In the center is an island, rising forty to fifty feet above the surrounding plain, and known locally as “Bogus Island.” It was the retreat of a gang of desperadoes in the early days, the surrounding marsh and lake making pursuit difficult if not impossible. I stood on the island in the midst of a sea of goldenrod and purple loosestrife that stretched for miles on every hand, seemingly as far from civilization as LaSalle when he pushed into the wilderness more than two centuries before.

Because it was slightly higher than the rest, this basin was one of the first marsh areas drained, a channel being cut through the northern ridge to empty into the Kankakee. The water level of this area is close to the surface even in the drier months, but the land is generally poor and subject to erosion by wind when the native grasses are destroyed. Being practically a drainage district in itself, this area would require the least construction of any to effect restoration to natural conditions.

The Jasper County area was most attractive from the standpoint of the conservationist, since the Cameron development is an index to what the restoration would accomplish within a few years. This proposed area· extends along the south side of the Kankakee, east and west from the point where the river forms its most northern apex and south approximately to the towns of Stoutsburg and Kersey. It would include some thirty to forty thousand acres.

A considerable portion of the land in this area is not good, much of it remaining in a semi-wooded condition through which forest fires have raged. There are scattered sections of wooded sand ridges and islands which could be planted with oak, the acorns again forming an important food supply for the waterfowl and wildlife that would be attracted.

The other areas would include a section bordering the lower reaches of the Kankakee, north of the Beaver Lake section, and the English Lake district which would be an amplification of the present 2,300-acre Kankakee game preserve. Development of these areas probably will not take place for a good many years.

Here, then, is the situation that I found with regard to the restoration of the Kankakee: The Grand Marsh is still there, potentially one of the greatest wildlife refuges that can be reestablished. Survey notes, maps and photographs complete to the last engineering detail have been placed in the hands of sympathetic Federal agencies for consideration. Two restored areas are there, pointing the way to what can be done, and the Indiana officials with a State-wide conservation organization of nearly a hundred thousand members are ready to cooperate in any feasible program.

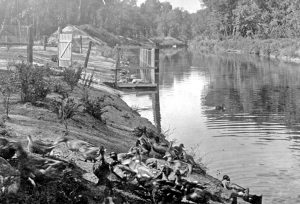

I spoke of two restored areas; one of these is the Cameron area and the second is on the Jasper- Pulaski State Game Preserve. The late William Cameron of Chicago pointed the way toward restoration of the Grand Marsh eight years ago. He had a thousand acres of bottom land along the old river bed; wild, rough, covered with scrub timber and unfit for anything but grazing. Deciding to turn this unproductive

land back into marsh, he tapped the river above his property and let the water spread over the land, the supply ditch being continued to the river at the lower end.

We tramped over a part of this marsh. It is a tangle of fallen timber and marsh grasses. The ducks are coming back-they say the number of migratory birds has doubled each year for the past four years muskrats are building villages and the water is teeming with fish. And not an acre of ground outside his own property has been adversely affected by the transformation.

Over at the Jasper-Pulaski State Game Preserve the showed me several hundred acres of restored marsh, where dozens of species of waterfowl find food and protection throughout the year. Here, too, the ducks are coming in increasing numbers to nest in the spring and feed in the fall.

I was convinced that the restoration is practical—that sometime in the future the Grand Marsh can be more than a myth-and that, when the restoration takes place, other generations of children on soft spring nights and frosty October evenings can strain to follow the faint music of migrating geese, knowing that they will nest at the Kankakee in the spring and find food there another autumn.

This will give you some idea of why the Kankakee had fish in it. It had ideal natural spawning and rearing conditions for fish. One season the river was alive with small pickerel weighing about a pound and a half. A boy friend and I caught eighty-seven in about an hour. He caught thirteen fish in thirteen straight casts of about thirty feet. On the fourteenth cast he hooked a fish and lost it. He threw his steel casting rod down in the boat and said, “Damned if this is fishing. It’s slaughter.” Then he lit up his pipe and enjoyed himself.

You could catch these fish anywhere for miles along the river. Where they came from no one knew. One other year we had a similar condition, but not so many fish, but larger ones ranging from four to five pounds. They must have had the natural feed all eaten, for they would hit anything that moved. Father and I caught fourteen in less than a mile of river. On one cast, when one hit his spoon, it jerked the end of the long cane pole into the water and another fish struck the end of the pole, the splash having attracted it. These years were the exceptions, not the rule, but we always had lots of fish. Many times, when we were kids have the kid brother and I dragged a string of fish on a dog chain which was too heavy for us to carry, from the boat landing to where the old cracky wagon and pony were left on high ground. Many and many a time have I looked over the edge of the boat and seen a school of bass or wall-eye in ten feet of water. The water was very clear and there was no pollution before dredging. It is not so clear since dredging but has no pollution even now.

In the spring of the year, after the ice had gone out and we had had our first thunder storm, the old fishermen would go dogfish spearing. They would anchor their boats on the shallow side of the river bend on a sand bar where the water was from four to eight feet deep and where the current would carry the fish over the sand. The fish would come lazily floating down, resembling sticks of sunken wood. They would come drifting along from singles to droves of six or eight and the fishermen would spear boatloads of these fish and salt them down.