AN ARCHER ON THE KANKAKEE

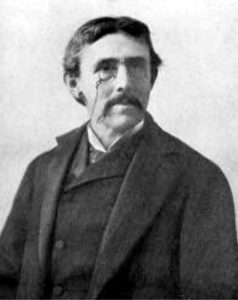

By: James Maurice Thompson

The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 85, issue 512 (June 1900)

The first opossum hunter on the Kankakee of whom we have a written account was La Salle; but his bag of game, if we may dare call a brace of ‘possums by a name so honorable, was killed in a wood beside the St. Joseph River just before the Kankakee Portage was reached. It was December; the year 1679, with a snowstorm slanting down from the Canadian wilderness, and La Salle had been lost for a whole day from his little band.

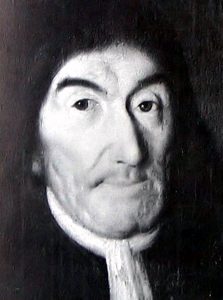

That space of twenty-four hours would have been, to any other man than Robert Cavelier Siour de La Salle, a most memorable cross section of his life; yet our fearless explorer doubtless regarded it as not worth thinking about. Hennepin’s sketch, our only source of information, is very slight; still, to one who understands outdoor life, it brings an immediate realization of what the wildwood wanderers experienced two hundred years ago in the heart of America.

La Salle and his men had ascended the St. Joseph River and were looking for the portage point between it and the Kankakee, which they had inadvertently passed. Restless, impatient, ever energetic, La Salle went ashore all alone to examine the country. His little company paddled some distance farther upstream, where they came to anchor and awaited his return. “We stopped here for some time,” says Hennepin, “and, as La Salle did not come, I went into the forest a considerable distance, with two men, who fired their guns to let him know where we were. At the same time two other men in canoes went up the river farther to look for him. In the afternoon we all got back after fruitless search, and on the following day I myself went up the river, but could hear nothing of him, and came back to find our men greatly troubled, fearing he was lost. But at about four of the clock in the afternoon here came M. La Salle back to us, his face as black as tar. He was carrying two animals of the size of muskrats, with fine, ermine-like fur. These he had killed with a club while they hung from the branches of trees by their tails.”

Hennepin then tells how La Salle had wandered in the snowstorm, getting lost in swamps and woods, and how when night fell he stumbled on until he saw a fire on a hillock, approaching which he hallooed in a friendly way. No answer came, so he strode boldly to the spot and took possession of a bed of grass, made warm by the body of the Indian who had just fled from it And here, after building a bush barricade, he lay down and slept, while the pine-wood fire smoked his face and hands to African dinginess. Meantime the snow fell thick and fast.

Now for myself, two hundred and odd years later, I can say that my sleep would be a trifle disturbed under the circumstances surrounding La Salle. Indeed, I awoke one fair spring night, not so very far down the Kankakee from the portage, to have a creepy feeling when but a bullfrog groaned close by. While I am not willing that it shall go upon the record as a case of fright, I cheerfully acknowledge my bewilderment just at the point of opening my eyes. The voice of that bullfrog exceeded everything bass and guttural to which my ears have ever listened. Nor can I, with a fairly willing imagination, make out how the grunt of an Indian scalp-hunter could have been more demoniacal. And then something cold, snaky, rusty, dragged itself, like one of Pope’s alexandrines, slowly along my jaw. It was an opossum’s tail, which I involuntarily seized with a terror-clutch, letting go at once when the animal snarled; for I recognized a certain rasping wheeze peculiar to its voice. This was the second time that such an experience had come to me. Once before, in the far South, a ‘possum disturbed a nap for me

La Salle’s brace of marsupials must have been young, else Father Hennepin did not well remember the size of a muskrat. I did not kill the fellow who touched me with his tail, and so cannot speak of his size: but in the Gulf States Didelphidae outgrow Fiber zibethieus beyond reasonable comparison, as it probably does in the Kankakee country. Hennepin does not give none to La Salle’s animals, yet there can be no mistake; they were ‘possums; for he found them dangling by their tails, a peculiarity of Didelphyae to be claimed by no other animal of our country, or of any other, if we leave monkeys out of the count.

It was well for me that a bullfrog and a ‘possum’s tail woke me that sweet night, when the moon had risen halfway up the east side of heaven; otherwise I should have missed hearing a veery’s nocturne blown softly from the dark foliage of a thicket close to my tent. A veery, I thought it was, at least; a thrush certainly, of one species or another, I knew it to be singing as if under its breath; but the rapture in the notes made the vibrations strangely powerful, and the first fancy in my brain was that they were like music filtered dreamily through rich honeycomb. It was almost unearthly melody, tender, solemn, hesitating now and again, as if the bird’s dream had its disturbance, yet the strains lapsed away, seemingly into infinite distance, seeking the remotest hollows of the night with their delicate, thrilling plangencies.

My tent (to call it one is a considerable risk, for it consisted of a rubber blanket stretched over some stakes) was near the river’s bank on a dry spot: Behind it lay a marsh, while on either side a thicket of maple, ash, and oak bushes straggled along a low ridge that ran almost parallel with the Kankakee’s current. There was scant room under my roof to sit up while I gave the veery audience; meantime away scampered the duly frightened ‘possum, leaving me to find out for myself next morning that he had been chewing the remnant of a prairie hen which I had stowed in a tin box for my breakfast. More than this, his curious hand like tracks were in my canvas boat where he had been prowling in search of eatables. Doubtless he was quite hungry, or he would not have been so daring. Wild things are finding it harder each year to get an honest living on their own grounds, and so they have to take greater risks when intruders tempt them with tidbits.

The veery’s night song was the cause of my staying five days on that lonely spot; for when morning came there was a haunting echo in my mind of certain strains, more like a dream than reality, and before I had rubbed the remnants of sleep from my eyes I heard a yellow billed cuckoo strike his tambourine. Then I wondered if there might not be something worth seeing in the thicket where the veery lived so happily that it must sing by night, and where the cuckoo could not wait till sunrise to begin his rattling monody.

A plunge into the river chilled me wide-awake. Three minutes later I was handling my archery tackle; not that there was any probability of seeing game. But a bow in the hand is worth two a quarter mile away in the tent, and I walk better when my quiver rustles at my side well filled with good arrows. The poetry of solitude stalks embodied as a sylvan toxophilite who goes alone into a primeval grove. I feel this in myself when I play the part with my imagination for my audience and the wilderness for my stage. On that particular morning the vigor of May circulating in the air gave promise of golden weather for a week to come, and it all crept into my blood; not a bird in any grove of the Kankakee felt more than I the keen need of song for song’s sake, and sing I did, silently, inwardly.

I had embarked upon the Kankakee with the purpose to follow La Salle from the portage near Fort Wayne to the rocks at Momence. At that time, I had charge of the Department of Geology and Natural History of Indiana, and I meant to make a fortnight’s vacation add something to my knowledge of a very interesting region, while at the same time I should have my fill of sylvan archery once more. I wished to be quite alone and quite unknown during this outing; for the politicians had their eyes upon me, and what would they have said of a state official who played “hooky” in the woods with a bow and arrows, when he should have been in his office chair with a case of fossils before him and looking as grim as Diogenes?

I found it not practicable to begin my voyage as high up the river as I had planned, and my present camping spot was at the end of two days of hard rowing downstream, a part of which took me over a beautiful lake formed by the widening of the river, which soon narrowed again, however, until at my stopping place it was pinched between wooded banks and ran deep with considerable current in the middle. There was a farmhouse on a prairie swell less than half a mile away beyond a marsh, while on the opposite side of the river I could hear cocks crowing at another homestead; but my tent stood ages away from civilization in a place not likely to be invaded by any beings save wild birds and wary animals. So much I found out by my morning’s exploration, as will better appear in a paragraph from my notebook : –

“Have found a most delightfully promising piece of wilderness; shall try its charms for a day or two, maybe longer. A chalybeate spring of delicious water a stone’s cast from my tent, two farm places not far away, and thrushes, – I have never before seen so many; they are everywhere in the thickets round about, blowing the flutes of Arcady’ even in the middle of the night.”

A pretty full record of my doings went into the notebook, from which, as well as front memory, I make up this chapter of joy. I got eggs from the farmer’s wife, and contracted with her for a large rhubarb pie to be sent to me with a pint of milk every day until further notice. A liberal bunch of young onions and some very small and almost over pungent red radishes were thrown in for good measure. I cut bushes and built a tent large enough for four men, thatching it with last year’s grass over the particular spot on which my bed was to be, and further covering it with my rubber blanket. I might have spared myself the work, for not a drop of rain fell during my stay.

There was a lagoon between my tent and the farm from which my supplies were to come, and I arranged for a boy to bring the basket of eggs, vegetables, and pie, and hang it in a tree at a certain point on the farther bank, where I could reach it by crossing in my boat. Thus, I shut off the only probable danger of being visited. To get into the lagoon I had to row some distance down the river, then double back, following a bilious looking and ditch like channel through a marsh. The spot upon which I was encamped proved to be the highest and driest part of a slight ridge or hummock between the river and the lagoon. All of the marshland round about was but a few inches above the water line, so that the wooded ridge was really an island a mile long, varying in width from a hundred yards to three quarters of a mile.

My first day slipped almost by before I could spare a moment to the birds, albeit in going twice by way of the lagoon to the farmstead, and in gathering materials for the bush tent, I kept the tail of an eye upon every feather that sparkled and every wing that flickered, thus mapping out, as it were, the places where I might expect success on the morrow. But at an hour to sundown, although tired, I went for a good tramp along the ridge, and did not get back to camp before dusk fell.

In my notebook is the following entry:

“No ‘possum last night. If any thrushes sang, the sweet noise was lost on me; not even the bullfrogs disturbed my slumber. Woke at daybreak with my ears overflowing, so strong the pour of morning’s tender discords. My eyes opened perfectly clear and ready for work, my blood felt fresh. One does not stretch and yawn when sleep slips off one’s brain in a wildwood lair. A gentle stir of the nerves, a deep breath, and then the sweet chill of a dewy touch; it is Morning on tiptoe at your Arcadian bedside, and there is an ambrosial richness in the first conscious taste of what she brings.”

I remember many a serenade at dawn by the thrushes of that May morning – it was very near June- were plus canora quam putes, as the old poet has it, and they literally deluged the wood with their gladness, – “Cantibus vernis strepebat et susurris duleibus.”

Brown thrushes, wood thrushes, veeries, catbirds, robins, – what a lot of melodious cousins! All their voices deliciously confused, were fairly splitting their pipes. I wonder if Father Hennepin and Father Gabriel heard the like while paddling down past my island? But no, it was winter. Jays may have jeered at them, flickers may have shown them the gold of their wings; as for the songbirds, they were far down by the warm Gulf coast. Besides, I feel sure that it is only since the woods have been narrowed down to mere patches that these birds have learned the value of mutual friendliness, and have agreed to share together, in the few ancient groves, what is left of original freedom.

Hennepin tells us, however, that the savages had been hunting buffalo on the Kankakee flats, and he saw the ground covered with horns where vast numbers of the animals had been slaughtered. Probably an Englishman, who corresponded with me a few years ago, had been reading the good priest’s account, for he inquired very particularly about buffalo hunting in Indiana! He might just as well have expected antelope shooting on our Kankakee prairies; for Hennepin says that one was killed by a hunter of his party while on their way down the river. The good Jesuit, it being winter, did not see or hear any “thunder pumpers” in the plashy flats, but my record mentions them frequently.

“This morning,” runs a somewhat blurred entry, ” I got a fine specimen of Botaurns mugituns, called by the Kankakee folk ‘thunder pumper’ on account of its rumbling voice. Good sport is bittern-shooting, too, if the archer doesn’t mind crawling in the mud through high, musty-smelling dead grass! ”

The note recalls many an adventure with the herons and bitterns, birds peculiarly interesting to me. I recollect very well how I worked in order to bag the thunder pumper, on that hazy and delightfully cool morning, between the Kankakee and the lagoon. A triangular patch of bog covered with last year’s grass three feet tall was the scene of my operations. There the birds were pumping thunder at daybreak, and I saw them flying in their awkward manner low over the slanting tufts, and dropping down into them here and yonder. I wanted one for dissection regarding its vocal organs, but I had no arrows to lose, and the thing was to be sure of my aim.

At sunrise, fresh from a cold plunge in the river, I began my campaign with all the strategy suggested by experience. My purpose was to approach very near to a bird, make sure of him, and so close the incident. An excellent plan, in theory, which when subjected to a practical test developed surprising and irritating defects, mainly on account of the birds, -they seemed not inclined to assist me in my difficult task. From the beginning, moreover, little mishaps worked me evil; but at last, to make my story short, I saw a fine point and got the benefit of it. One of the birds, after a short flight, dropped into the grass twenty yards beyond a clump of low shrubs behind which I crawled to position. Musty smelling was that grass; it was more; the smell suggested the quintessence of malaria. In the little pools, through which I went on hands and feet the water looked red with a purplish iridescence on the surface. The colors were due to oxide of iron from bog ore in the soil.

I had to hang my bow around my neck, and let it lie along my back while crawling thus; and a very unwieldy, troublesome appendage it was, catching in the grass and weeds and interfering with my legs at almost every stop. When you try it, as I hope you will some day, you will find your temper much opposed to suavity during such a crawl. The cool air and the damp grass did not hinder perspiration; I was beaded all over when I reached the clump of bushes and began to lift myself erect. My hands were as muddy as a hod carrier’s, quite unfit to lay hold of a bow or an arrow with, and while I was wiping them on a wisp of grass, up and away flew my thunder pumper!

It is a strong stipulation of the contract, when you bind yourself to sylvan archery, that you will not feel aggrieved at any bird for giving you the slip just at the most exciting moment of an adventure. So I stolidly accepted the rebuff to expectation, and stood there gazing aimlessly upon the spot left vacant by my vanished game. At that moment an indirect ray of my vision fell upon something as brilliant as a diamond flaming star like just beyond a tuft of greenish water weed at the edge of a pool Out went my bow-arm and bow, swiftly, gently; and to the string of the bow my right hand fitted a broadfeathered arrow. It is stale to say this, but every shot is a delight to the archer, and a thunder pumper’s eye is a good target even when you miss it, as I did.

My notes inform me that I shot eleven times during two hours of hard crawling in the grass before I bagged my bird. On paper the whole proceeding very little resembles good sport, but the archer who reads will understand that the sport was there. At this moment I seem to hear the breezy “whish ” of those broad feathered shafts and the sodden “chuck ” of each at the end of its flight. In the midst of my pursuit, and while every moment added to the wariness of the bitterns, I flushed a rail, -fairly kicked it out of the watery grass at my toe’s end, – and I risked a shot. The bird flew lazily, with its

characteristic flutter, straight away four or five feet above the grass. Going thus it was as easy to hit, almost, as if sitting on a tussock; but when I bowled it over in the air I could not repress a cry of self-admiration. I was my only audience, save some red-winged blackbirds swinging on tall dry stalks of rush at the rim of a pond. These encored me while I was searching for my arrow, which I at last found half buried in the black mud.

The following bits from my notebook will smack of what I cannot describe; at least they will:

“Pill in the symphony between” What I did and what I felt.

“Found brown thrushes nesting in a tangle of low trees. The nests, three of them, lay flat as saucers on the pronged boughs. The wind blowing hard would surely whisk them off, as it so often does the nests of doves. A scattering, loosely woven platform of sticks with a shallow cap in the middle is all that a brown thrush’s nest amounts to. The wood thrash adds a daubing of mud to the leaves and grass of its well – built nest, while the veery makes a clean and pretty little home (sometimes on the ground, never far above it) almost exactly like the nest of the hermit thrush.”

If I could, I would stay right here a month to enjoy the bird song. Even the blue jay sings sweetly -or flutes, rather, in a soft, wheedling, minor. I hear one now. ‘tee-doodle-doodle-doodle,’ a tender, melodious iteration and reiteration of love. ‘Doodle-tee-doodle-doodle-doodle.’ he goes on and on right overhead, and I note it down phonetically. But I can’t record how he acts meantime. His motions are absurd. Every time that he says ‘doodle’ he wags himself grotesquely and seesaws his body up and down exactly in time to his tune. He looks like a fool; but he isn’t.”

“Below here, scarcely two miles, I found where a party of sportsmen had camped some days ago. From Chicago, doubtless, for they left some monster newspapers- Inter-Ocean, Times, Journal – and two or three letter envelopes with Chicago addresses, not to mention sundry cans and bottles remarkably empty. Near this spot I made a fine shot at a woodcock, – out of season, but precious good to eat, -and bagged it for a broil. It is broiling now with expanding savory fragrance. Rowing back upstream I met two summer ducks midway of the channel. Of course my back was toward them, else they would never have let me come so near. When they flew up and away their noise gave me the shock well known to sportsmen, – the thrill of what might have been. It was a fit of reverie that caused the carelessness. At the time I was with the Muse of the waters, listening to the river’s cool song!

Many of my notes are too frankly ornithological to make pleasant reading. I was dissecting throats, with remarks upon glottis and bronchial, and syrinx valves, etc. Plainly, however, recreation pleased me more than work, -the bow claimed far the greatest share of attention and use, while knives and needles and pocket lens did the best they could.

Here is what I put down in the way of comment upon the fletcher’s art. I copy it that my readers may feel, if possible, how delicate must be the handiwork in making a good hunting arrow. The craftsmanship of the true fletcher is next to the poet’s. A winged shaft and a winged song are worthless if genius be not in them.

“Among my arrows there is one that ‘wags.’ That is, it wobbles in the air and will not go true to the aim. In every particular it is faultless to the eye. Straight as a star beam, smooth, even, neatly feathered, solidly headed, notched to perfection, it should fly like a bee; but it doesn’t. It wags horribly as soon as it leaves the string. A vexatious fascination in this problem has caused me to waste a deal of precious time whittling and trimming and scraping all to no good effect. -The arrow wags worse and worse, apparently with much delight. And it seems that I, through some instinct of perversity, share the thing’s constinate contrariness; for unless I take especial care I am sure to choose it whenever a particularly nice discrimination is to be made with a shot. Example: In the sweet of the morning I was sitting on a log, a quarter of a mile from my tent, thinking shop. In other woods, a lyric was stirring my blood and illuminating my brain, when a very prosy scratching or scuffling sound in a tree nearly overhead brought me up short against reality. The first glance aloft set my gaze upon a supremely savage object outlined vigorously against a spot of blue sky in a rift of the foliage. It was a white owl with a bird, still feebly struggling, clutched in its talons. An atrocious glare and an expression of unbridled rapacity flashed upon me from its countenance, which was hideously human in a way. It was about forty feet above ground on a stout maple bough, a fair shot, but a trifle steep. At first it looked snow white and very large, enormous indeed, on account of its partially extended wings and a vicious lifting of the feathers of its breast and neck. A snowy owl – Nyctea scandiaca- I knew it to be; a rare bird here, and so late in the season. I had to get upon my feet to shoot. But the owl had not seen me; its glaring flame-colored eyes were fixed upon the bird under foot. Just as I was in the act of settling upon my aim, it discovered me; and such a stare! I had to steady my arm again. Then, when it was too late, I saw that I had chosen my wagging shaft! Of course, the usual antics were performed, the feather seesawing with the pile and making the shaft shy away leftward. At the same moment the owl flew, dropping its prey. But what did I see? Arrow and owl met in the air-whack! Thereupon I danced and yelled. Give me a wagging arrow for luck! But I had to change my mind suddenly. The shot was a glancing one between wing and body, knocking out a bunch of feathers, nothing more. Away like a ghost flickered the pallid bird. I picked up its victim, which was a Wilson snipe, and never went to look for that dastardly arrow. Let it rot where it fell.”

I might now add to this note some of old Roger Ascham’s fletcher wisdom; but even he left the mystery of the wagging, “or hobbling” arrow, quite unsolved. Says he: “Yf the shafte be lyght, it wyl starte, if it be heuye, it wil hoble.” I have tried every trick of the shaft-maker’s art to very indifferent effect, -a wagging arrow is incorrigible. Sometimes use will cure the defect; how, I do not know, possibly by slightly wearing the feather. Ford, the greatest of English target archers, in his book, Archery: Its Theory and Practice, avoids our point. He merely says: “Two things are essential to a good arrow, namely, perfect straightness, and a stiffness or rigidity sufficient to stand in the bow, that is, to receive the whole force of the bow, without flirting or gadding.” But a stiff arrow will sometimes gad or wag just as persistently as a limber one. Ascham was nearer right than Ford. An arrow too weak for the bow will “start,” that is, quiver and shake; but one will hobble or wag apparently without reference to either stiffness or limberness. Yet I have tried trimming the vanes, or putting on different ones, without success. That the defect is nearly always in the feathering, seems to me, however, quite certain.

On the last day of my stay in the Kankakee camp I arose before daybreak for fear of oversleeping. I meant to resume my voyage down the river early in the morning, but wished first to take one more “round” in the wood. I packed my things in my boat, after a light breakfast, so as to be ready to embark, and was off toward the lagoon just as a gray light dulled the eastern stars. There was a keen, peculiar freshness in the air, which, as my note reminds me, blew out of the northwest with almost a hint of frost. It gave me a sense of strength and energy; I felt as if it would do me good to frisk and gambol and shout. At the same time a sly, furtive, predatory instinct controlled me. In the twilight all was strangely silent, save that the breeze whispered in a large, comprehensive phrase.

A brisk, noiseless walk of five minutes bore me deep into the wood, where, in obedience to a habit of long standing, I halted behind a tree bole to listen and peer. For you must learn that one’s eyes and ears are quicker when one is motionless. I swept the solitude deliberately, gazing expectantly down every aisle, hearkening with a certain delightful flutter in my blood. In one direction the brownish gray water of the lagoon shimmered beyond a scattering growth of tufted aquatic grass. A tall object suddenly held my eyes, -a great blue heron, stock-still on one foot, his neck partly folded. Of course, he was in full plumage; I could see the long, streamers at the back of his head. ” I should like those,” I thought, or rather felt, while swiftly considering a plan of approach. Then, as if by premeditated action, the songsters began for the morning’s melic battle; and what a tune they marched me to! I stooped and crept from cover to cover, light of foot as any cat; but the shot would be a long one for my heavy arrows with their wide feathers, as the strip of shore marsh on which the heron stood prevented close approach. Fifty yards I call long range when using heavy-headed bird-bolts. From cover of the last bush I carefully estimated the distance to be forty-five paces, and then drew up. Beyond the bird a line of silvery light began to twinkle on little choppy waves. This was hard to overcome, for it shook my vision and interfered with fixing a point of aim, which I felt had to be above my target. Then, too, allowance for the drifting force of the breeze was a nice point to settle. A heavy arrow with a broad vane does not resist a side wind very well. Not more than two seconds elapsed, however, before my bow added its ancient note to the woodland medley, and ” whish-sh! ” whispered the arrow, going with tremendous force. I say tremendous, and hearing it hit you would not erase the adjective. Although its trajectory was high for so short a flight, the arrow went like a flash, and, as true as it was swift, struck solidly with a successful sound.

When I measured my bird, his dimensions were recorded thus: “Length, fifty-one inches; extent, seventy-three inches. The biggest one yet! A fine trophy (his plumage) to bear home. It was a great shot in the crack o’ day, forty-five yards. Had to wade in black mud a foot deep to get him.”

It was but little past sunrise when I pushed away from my pleasant camp and rowed downstream past the bayou’s mouth, once more pursuing La Salle and Hennepin. In the stern of my boat lay a bloated rhubarb pie, four hard roasted eggs, and a sharp stick decorated with slices of well-broiled bacon. My mode of progress favored natural aversion in me to hard labor. Every now and then something worth noting stopped me short while I wrote it down in my notebook, or a bird inveigled me into dallying by holding out flattering signs of approachability. I stood up in my boat and shot four arrows at a killdeer, which squatted flat when my first shaft just grazed its back. I have often seen a quail, a meadowlark, and even a woodpecker do this; but a killdeer never before or since, I think, was known to take such a risk. It had the laugh on its side, however, in the end; for after sitting there until I had stuck four shafts deep in the ooze all around it, it gave forth a derisive cry and flew off across the marsh. I soon discovered that I could not get to my arrows on account of quicksand surrounding the spot where they had struck.

At the end of an hour’s work, however, I lassoed them and drew them to me with a abetted fish line. It is a part of an archer’s religion to be faithful to a good arrow, and all four of those were perfect missiles in every way. Three of them I still have. Since then they have been shot in some wild places. The fourth one I lost by breaking it when I tumbled down a twenty-foot bluff with it in my hand. I know these shafts from all my other arrows by their steles of wagon-spoke hickory and their extraordinary weight. At short range they are more reliable than the best London target arrows. I have made others very much like them, but (it may be imagination) the old ones are best.

There are notes sufficient to make a good stout book in my Kankakee memoranda, and next to going on the voyage again, I should enjoy expanding them into literature. My space, however, is almost full. One more entry I will copy and have done:

“When I reached the cabin of the Crawfordsville Fishing and Shooting Club today at noon I found it empty and fast locked, much to my discomfort; for it was threatening rain, with a chill wind from the east, and gray, sad clouds all over the sky. One of my subordinates in office had promised to meet me here, where a railroad crosses the river, and I was expecting important mail. The place looked forlorn; something in its air impressed me gloomily. Under the building, which stood upon stiltlike posts, was a fair shelter. But the clouds went away before the east wind with little rain, and now it is cold. I am ten miles below the clubhouse, camping on the edge of a prairie. Reached here at four o’clock. Chickens (grouse) on a dry swell of wild prairie southward. Went after them. a hungry man regards not the game law of Indiana, and had a breezy time shooting. They were net very wild: or possibly the stiff, piercing, east wind numbed them. I tramped around after them and shot perhaps fifty times; but the wind caught my arrows with rough hands and tossed them up, down, sidewise. It was almost impossible to foretell the drift of a shot in extent or direction, and the wily birds somehow would manage not to be down the wind much of the time. I killed but one, and that in a remarkable way. The wind every moment increased in velocity, finally becoming gusty, changeful, as if about to shift southward. (It is now blowing hard from the southeast, and still growing colder.) I had nearly lost hope of bagging a chicken and had turned a shoulder to the breeze, when something whistled, or chirped, close behind me. At the same time wings fluttered, and upon turning I saw a cock grouse in the act of alighting beside a tuft of prairie grass not more than six feet from me. When he struck the ground he erected all of his feathers and looked at me wildly. I had twisted myself and was turned but half around. I saw that he was going to fly, -I must shoot instantly or not at all. It was an awkward situation. Then a new feature was added. Flying like a bullet came another cock and struck the first, whereupon the two fought like savages, tumbling on the grass, striking with their wings, pecking, kicking, chattering. Evidently they were bent upon killing each other if possible. I let drive an arrow at them and missed. Shot again and knocked one over. The other flew away in crazy haste. On my way back to camp I passed through a scrub-oak grove on a low, sandy ridge lying at right angles to the river, and in the midst of it found a pond literally swarming with ducks of different species. They must have sought the sheltered place to avoid the chill and worry of the wind. It was deep water and the birds kept well out from shore, so I did not shout, as every arrow would have been lost”

Next morning the sky was clear, the weather calm, with a delightful freshness in every breath, and I rowed back up the river to the clubhouse, where I found my clerk just arrived from the little town near by with my mail, in which I discovered that I should have to go to Indianapolis on the next train. So good-bye to the trail of La Salle, and farewell to the birds of the Kankakee.