ONCE UPON A TIME

Once upon a time there was a small boy who lived in the City of Lafayette, in Tippecanoe County, and the State of Indiana who was particularly blessed. He had a devoted mother and father, two living grandparents and an aunt, the sister of his mother, who lived with them. He also had a collie dog named “Laddie.” Because he was an only child d everybody was concerned it should not be said he had been “Spoiled Rotten”, he was surrounded with more than the usual observation, parental and grandparental, diagnositical analysis. Nevertheless, despite this abundance of attention he was able by the time he had reached age 71, going on 72, to have lived through, and survived with some degree of success, the panic of 1907, the election of Woodrow Wilson in 1912, World War 1, the Tea Pot Dome, the League of Nations, the depression of 1921-22, the election of Franklin D. Rosevelt and Sisty and Buzzie in the White House, World War II, the Command and Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, and the elections of Harry Truman, Dwight Davia Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, L.B.J. and Richard Milhouse Nixon. This was due, no doubt, not only to a certain unreconstructed capacity to resist external pressures but also to the era into which he was born, and which might have been_ called not with over-much accuracy, of course, the “American Edwardian Age”.

This, like it’s British name-source, was a study in contrasts. But what goodness there was in it dwelt in the solid virtues of the middle class. It was a day of relative innocence about the great world, then quite remote to the understanding of unsophisticated Americans and in particular, Hoosiers. Perhaps those years might better have been known as the “James Whitcomb Riley Age”.

Looking backward in Riley’s mood, one might have said, “Do you remember, Oh, brother mine, the golden days of the lost sunshine—of Youth?” Perhaps it was the humdrum of rural and small town life in those early years at the infancy of the new century, the unconcern with the world of foreigners, that built up the confidence of the middle class American that would stand him in such stead during the years then yet to come. It was a time, in its calmness, reminiscent of the former century at the mid-term antebellum years which, when ruptured by the guns of Sumter, could, nevertheless, send over 200,000 Hoosiers to the Union army. It was a time when the Hoosier farmer, the April sun upon his back, the black furrow turning beneath the plow, could feel in his bones “This is my own, my native land.”

It as a time also for an ingathering of strength, devoid of national urgency, posing the question whether America as the example of all that was good, right, and true was or was not politically, as to its national, as well as its religious leadership, in the position of Nicodemus to whom Christ had said, “Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again, The wind bloweth where it iisteth and thou hearest the sound there of, but canst not tell whence it cometh nor whither it goeth.” And, so, in this, one of the most interesting periods of our history, there was no adrenalin of national crisis; that had ended with a stillness at Appomattox, and even the Maine was remembered only briefly. The world, among the small fry, in Lafayette, for excitement rather revolved around the budding automotive explosion.

For example, old Doc “V” who lived on Hitt Street and was an osteopath, got the jump in technology on the M.D.’s by acquiring a four wheeled horseless carriage that ran on rubber tires held up by nothing but air. It had a front seat and a back covered with leather, two front headlights bound in shiny brass, a cloth top and open sides. When running, it shook so hard it made your teeth rattle. In order to start this monster, the operator stationed himself in front with an “L” shaped crank, delivered after prayer, the monster began, if lucky, to shake after which the operator scrambled as quickly as possible into the driver’s seat to advance the park or the gas, or whatever. If this maneuver was successful, which was evidenced by the continued shaking of the monster, the driver did things with his feet upon divers and sundry of three pedals which projected from the floor in front of him and the ride began. Sometimes on a Saturday when old Doc had a patient out in the country who was too miserable to get to the office, Maggie, his daughter, would come over to the boy’s house to say her Daddy had to give somebody a “cheatment” and did the boy want to take a ride? The boy always was willing to undergo the novel and almost frightening experience. The portable operating table already occupied part of the back seat, so both children sat in front with the driver, where all the operation of the shaking vehicle could be plainly seen. Next morning at school there was always some opportunity to mention the experience. In case anybody asked what kind of car it was, the boy was always ready with the answer, “It was a “K.T.V.” and this was literally true, for 0l Doc’s initials were plainly and neatly painted on the outside of the right-hand front door. This was the boy’s introduction, together with a metal erector set, given at Christmas, to the dubious wonders of the mechanical age. In those days of innocence, of a slower pace of life, there was no awareness of radio, no air travel, no television, no traffic lights, no super highways, and no computers. Women’s rights were just a gleam in the eye of Carrie Chapman Catt. There was no League of Women Voters.

In school, readin’, writin’ an’ ‘rithmetic were administered in daily, painful doses. Progress was measured on a simple scale; you either passed or you didn’t pass. Pupils were then unharrassed by disciples of John Dewey and there was no known head shrinker in the County. Discipline was also a relatively simple problem, ranging from deprivation of recess or after school detention for minor infractions, as for example, heaving an eraser or a paper wad at Billy, to a paddling in the cloakroom for sticking a girl’s pig tail in the ink well. Rewards were even more impressive in this primitive system. They could be individual, like being detailed to help teacher by beating the chalk dust out of the erasers after school, or, in group, when everybody had been good, and it was, maybe, Washington’s birthday and teacher would pass out the song books and say, “We will turn to page 57”. When the page rustling was finished, she would sound her pitch pipe and everybody would sing,

“Hail Columbia, happy land;

Hail ye freedom’s heaven born band

Who fought ‘an bled in Freedom’s cause

Who fought ‘an bled in Freedom’s cause.”

or sometimes it might be,

“Oh, Columbia the gem of the ocean;

The home of the brave and the free;

The shr1ne of each patriot’s devotion;

The world offers homage to thee.

Thy mandates make heroes assemble;

When liberty’s form stands in view;

Thy banners make tyranny tremble

When borne by the red, white, and blue.

When borne by the red, white and blue,

When borne by the red white, and blue.”

On the other hand, if teacher had been pushed almost beyond human tolerance and still had kept her professional cool, the day might end with a four-part rendering sung by all present, of:

“Now the day is over;

Night is drawing nigh,

Shadows of the evening,

Steal across the sky”.

It was hard to go back to school in September for an aging summer was still on the land. When the day was rainy, thus adding to the general gloom, things were a little easier, for you would have had to stay indoors anyway. The boy, even on rainy days, rode his tricycle all the way to old Columbia School, a four room, two story on Owen Street. The little boy’s mother had arranged that instead of the shorter trip to Ford School, because the ordinary school child route ran beside the Wabash Railroad tracks. The only drawback was that the ancient maiden aunts of a little neighborhood girl, had made the same arrangement with the school superintendent. So the little girl went to Columbia School as well. This could, of course, in time be tolerated, but the immediate side effects were sometimes unfortunate.

On occasion the other boys near the destination were prone to pick on the little girl. As a consequence, the little boy usually came to her defense, not from motives of chivalry. That time of youth was unacquainted with such gallantry but stemmed, rather, from an odd proprietary sense based purely on geography. These ruffians were from a different part of town and alien. The little boy’s conduct was, nevertheless, sufficient to cause the little girl’s aunts to call the little boy’s mother on the telephone, (The telephone, even in those ancient days, was in almost constant use between female type persons who had children in school). Further consequences resulted, for the little boy, as a result of this phone call, became known to the ancient aunts and his mother as the little girl’s protector”.

This, of course, was intended by all the unknowing adults involved as a compliment to the little boy for conduct above and beyond the call of duty. However, this burdened the boy with the obligation of repeat performances upon subsequent similar circumstances. Without an intention on the adult’s part, this was a lesson to the little boy about what kind of trouble a fellow can get into if he weren’t careful. He was rather in the position of a soldier, who, having been decorated with the Congressional Medal of Honor, for repulsing an enemy attack at bayonet point, of coming up with a repeat performance on subsequent assaults, during none of which he was feeling like an encore.

However, the little boy also discovered that what must be borne can sometimes also, by deep thought, be avoided. One of the best ways to avoid further heroism was to get up ten minutes earlier and be on the road before the little girl came in sight. After going up South Ninth Street to the level by Doc Wetherill’s house whence the sidewalk continued clear to Kossuth Street and was easy for rapid pedaling, appearance of the “protected” far to the North by Doc Wetherill’s house was too far away for the stage coach to call the cavalry escort to the South, and if the escort did not look backward it could proceed thence schoolward in peaceful conscience-free enjoyment of the road ahead.

There were all manner of dangers to be avoided and enjoyments for knowledgeable frontiersmen, when unencumbered by dependent females. Here was a rushing mountain torrent to be crossed by wheeling the tricycle through the gutter of Pontiac Avenue instead of crossing on the wooden foot bridge provided by the city fathers. Next there was the furious assault of a grizzly bear, in fox terrier dress, rushing from his den disguised as Wallace’s front porch, but which never nipped unless you tried to give him a kick. Then there was the cool mountain lake in the triangle of the big grass plot of Highland Park, a lake masquerading as a fountain in this grassy heaven in the midst of the western desert, as the first bell had not rung, there was time for a rest from the heat of the day, which had begun to tell as the cavalry had been riding hard. Nothing would serve the purpose as well as a ducking of the head, ears and all, in the moss-covered bowl of the fountain.

By then duty would call and the cavalry, greatly refreshed with plastered down hair and a wet shirt front, was on its way to the two vacant commons to the west opposite the school. Here the trail forked. The trail to the left ran along the sidewalk and was easy for the tricycle. However, the road straight ahead across the commons was more adventurous. There were oak trees there, which in the Fall strewed acorns everywhere. So far as the boy ever discovered, they had no useful purpose, even to grownups, but they must have been truly valuable, as his mother could have testified from the contents of his jacket pockets never knowingly thrown away. Also, ahead, along the cross-lot trail you could never tell when a rabbit might not jump up and go dodging about in the sumac and blackberry bushes. But by now the school bell would be ringing and the little girl would say, “Where’ were you, I looked everywhere”.

After Columbus Day, which wasn’t very exciting, because you didn’t get out of school in Indiana on that account, there was nothing to do but wait for Thanksgiving. This was worth taking note of for two reasons, first, there was always a big turkey at grandmas and second, it then would not be long until Christmas. And everybody knew about Christmas.

Grandma’s was familiar territory, She and Grandpa lived on Sixth Street in a brick house which had been a station on the Underground Railroad, before the Civil War and William Lloyd Garrison had even stayed there when he came to make a speech about abolition. Grandpa and Grandma had all sorts of interesting things around, like a shingle from Brandywine Church, two rattlesnake skins from Florida that were six feet long and six inches wide in the middle, two pairs of buffalo horns, an Indian weapon with a whip of horse tail on one end and a stone at the other. Over the handle and the stone was stretched what had been a green skin, that in drying had shrunk and held all tight the horse tail for whisking flies and the stone at the other end for cracking heads. This was truly a marvel. Also, there was a cannon ball from the Brandywine battlefield. Best of all, there were four bound copies of Leslie’s Weekly, a forerunner of Life, complete with pictures of Civil War battles, one volume for each of the four years of the struggle, then only a generation in the past. The years 1863 and 1864 were the the best and the little boy on Thanksgiving, while waiting £or dinner to get ready, which never seemed to come, used to lie on his stomach on the couch and slowly turn the pages to examine in great detail, but only the pictures, which were on every other page, This was also great for Sunday’s tor the whole family adjourned to Grandma’s after services at St. John’s Church.

After Thanksgiving, the days toward Christmas dragged on leaden feet. Sometimes it seemed to the little boy that much of life consisted of nothing but to wait. You had to wait for Christmas to happen. When you hung up your stocking on Christmas Day you had to wait until Grandma and Grandpa came on the street car, because they always went to Church on Christmas morning and after they did come there had to be dinner at noon before the main event. No doubt this was all considered by the grown-ups to be very character building. But, to the little boy it often seemed that lite consisted of mostly character building, which was good for you, although no one ever explained against what weaknesses and temptations he was being prepared.

After Christmas, there wasn’t a thing worthwhile in immediate prospect except. New Year’s Day which wasn’t really very much, not being connected with presents, or turkey and such. So, after New Year’s there wasn’t a thing ahead and you just had to wait for Lincoln’s birthday unless it snowed hard enough to go sliding.

Lincoln’s birthday, however, was something special because everybody got out the flag even if it was just to hang it up in the house, Strange to say, not very much filtered down to the small fry even though the conflict was only a generation away. They did have it though, that something bad had been thwarted and that right had prevailed. Nobody ever referred in those days to a War between the States, and rarely to the Civil war. It was always the War of the Rebellion, as Grandpa, he kindliest of men, used to say as he clamped shut his toothless gums and blew his nose and sought to change the subject. Maybe it was just too painful for the old folks to recount to children that the 20th Indiana Volunteer Infantry had been raised in Tippecanoe County and had fought in the Devil’s Den at Gettysburg and on the second day had lost over half of the command including the colonel, in Longstreet’s maelstrom of lead and steel. As well might have been wiser, teacher sometimes had old Mr. Jackson, a veteran, who had been in Washington D. C. on that tragic night, recount his experience at Ford’s Theater. The children from memory recited the prescribed quotes she had assigned respectively to each pupil–doubtless in accordance with their respective abilities.

“A house divided against itself cannot stand”

“A man cannot serve two masters,

With malice toward none,

With charity for all”.

Nobody ever got mixed up in his quote and nobody got nervous that anybody else would get mixed up. In this way it was like St. John’s Church.

After Lincoln’s birthday, Washington’s came next, and you could hang up the flag outdoors in case it were not raining. And by then most everybody thought they had a handle on Spring in spite of the foot snowfall that closed the schools for three days. That gave plenty of time to roll a lot of big snowballs and build a snow fort in the front yard so as to ambush the Catholic kids when they went home from Saint Mary’s the next school day. The ambush was well planned. The Fort garrison did not dally after school next day and came straight to the Fort and carefully hid behind the ramparts. Ample ammunition in the form of packed snowballs was at hand. Along came the enemy and the Garrison rose with fierce shouts, letting fire with volleys of the ready prepared ammunition. However, the unpredictable God of Battles then took a hand in the form of a half load of anthracite coal lying on the sidewalk across the street. The Garrison was then met with volley after volley of Coal, handy size for throwing and of stoney hardness and a charge upon the Fort. Most unfairly the enemy had a secret weapon. They had with them a number small brothers who were converted by the combat troops into ammunition carriers, so that when their big brothers reached the Fort they had all kinds of ammunition for throwing at short range. The Garrison ignominiously fled to the safety of the house. There they suffered the indignity of not only the shouts and jeers from the outside but the aided humiliation of having the front doorbell rung in their faces as well as the demolition of the fort. Mother’s voice tram upstairs, aborted a possible rally on the spot. Ma said she didn’t want any windows broken. Higher authority had spoken, and everybody’s face was thus somehow saved. -There was quiet agreement among the defeated Fort defenders that “next year we ought to pour water over the fort right after she was built in the late afternoon

And let “er freeze”. Nobody had suggested about how to meet the ammunition problem except maybe to pack a rock in each snowball. Thus was the military axiom again demonstrated that combat is the mother of a more lethal weapon. The day after the big snowball right it rained for two days. When the sidewalk dried and the sun came out, everybody, all the boys, had a pocket full of marbles.

The game then had very strict unwritten rules, enforced only by the strength of social pressure. The method of play was for the boy who had a target piece to sit down on the sidewalk with the target piece just ahead of the nearest handy crack in the sidewalk so that the other boys could roil their plaster, less valuable, marbles at the target piece until it was hit. Whoever hit the target was then privileged to take the former owner’s place while the other boys tried to hit the target piece. The target pieces were of different kinds depending on size and “beauty”. As for example, there were in increasing sizes two block agates, three black agates and four block agates. Or what, by size otherwise was a four blocker might if clouded, for example, a misty grey with beautiful whorls in it, be designated a five blocker and a “moonie”. The marbles used for rolling were called “doughnies” and a large accumulation of “doughnies” was highly desirable because they were the source for accumulation of the real wealth—”agates” and “moonies”. When someone had hit the target piece and had taken the place of the former disconsolate owner, he was apt to yell, tauntingly, “Roll in the doughnies, roll in the doughnies”. When a boy was out of doughnies he was, though, period. There was no borrowing or lending or doughnies even between brothers or best: friends. Pride forbade such a thing: For a former owner to whine around and ask for the return of a lost agate was unheard of. Doubtless it would have meant social ostracism, at least for life if not in the world to come. This was very character building and doubtless saved many a boy from ever being addicted to poker.

Another rule was also a character builder. When a boy had hit the target he was not privileged to run home with it. He was bound simply to take the former owner’s place so that it could be shot at until the former owner, and anybody else originally in the game, was out of “doughnies” and the question was asked: “Are you busted” and the answer came back, “Yeah”. Then the game was over and when the little boy’s mother asked why he was late for supper she got the answer “Oh nothin” Beautiful agates were treasures kept from year to year. They provided another moral lesson; if you didn’t want to lose them, you didn’t put them down. And, you just showed them to close friends.

Spring sometimes came with a rush. One day it would snow, the next day the sun would be out and the next day after that the fountain might be flowing in Highland Park. You could stick your head in the water again to the ears. And if the little girl came along, you might just walk along with her until almost school. “Your head all wet, she’d say, just before you pushed Beany off the sidewalk and got into a rassle with him, to rebut any idea he might have had that you and the little girl had been walking together—on purpose. You hoped that Beany would put it down that it was the Spring that gave you extra energy. This was in part true because the season of the year meant the end of dancing lessons at Allen’s Academy which had gone on for eleven dreary weeks after Christmas. Attendance by the little boy every Tuesday after school was not voluntary on his part, but rather, by order of higher authority. The actual lessons weren’t so bad, It was what went with it. For example, you had to put on your blue serge Sunday suit, although it was in the middle of the week. This would then prompt an embarrassing remark from Beanie, such as “How come you all dressed up? You gain’ to a funeral?” You did not dare counter this by putting Beanie down on the ground as he richly deserved. This might tear the suit or lead to further insults such as, “Hey look at the dude. Betcha he’s goin’ to a girl’s birthday party.” The only course really was to hear these remarks in aloof silence and pray for the bell to ring. This was a character-building experience.

Another agony was worse. You were compelled to take along to school, in going back in the afternoon, your dancing pumps. These were low heeled, shiny and had a bow over the instep. Their concealment in a black bag, drawn tight with a string, didn’t make things much better, for the little boy was always in mortal terror that somebody, while the bag was hanging in the cloakroom, would peek inside and then publicly reveal his shame. It was always with relief, when, carrying the bag as inconspicuously as possible, he boarded the Owen Street streetcar for the trip downtown.

Once there, it was better, and some of the girls were pretty—well sorta of. Mr. Allen required partners to join up higglty pigglty, the only consideration being boys and girls of the same approximate height. The girls were carefully seated around the hall, backs straight, hands in the lap. The boy was required to approach respectfully, stop a pace away put his left forearm “across his “Stummick”, his right arm behind his back, bow and say “please may I have this dance?” The victim, if not previously bespoken was required to arise, curtsey and say “Thank you very much, I would.” Then. after some preliminary instruction, Mr. Allen would say, “Now we will dance as partners” and would clack his castanets for the music to begin, “Ah, one, two, three; one, two, three”, Mr. Allen would say, as the pairs struggled in what was intended to be the waltz. The two-step was also included in the repertoire. And then one day he introduced the tango. Somehow this gave a feeling of wickedness—almost like flirting with sin. Therefore, dancing school began to take on some social prestige, but the boy was careful not to say anything about this at school, or even at home. Experience had taught that adults could not be trusted beyond certain limits. You could never tell exactly what their limits were. Dancing school had however, achieved a status trudging toleration and besides, next winter was a long way off. The big event now to look forward to was Decoration Day, especially if it came on a “school day.”

Decoration Day partook somewhat of other holidays. Like Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays and the Fourth of July, it was a patriotic day. You were supposed to put out the flag early and did so. Also, it was like Thanksgiving Day and Christmas, with things that were good to eat—a picnic outdoors in the yard, sitting on the ground with little flags all around the tablecloth, standing upright in empty milk bottles. There was always homemade strawberry ice cream or maybe short cake with mashed strawberries from the garden and a big pitcher of cream, each portion in a soup bowl with a large spoon. This when following fried chicken, mashed potatoes with gravy, and peas was enough to put the hardiest trencherman sound asleep at the end of the day, which had already been one filled with good works. In the morning, right after the flag went up on the flagpole, set in an old drain tile, left all year round to receive it, the next thing to do was to cut a lot of flowers from the garden put them in tubs filled with water until time to go to the cemetery—peonies, iris, gladiolus, sometimes lilacs, tulips and syringa. When all was assembled in baskets, the family would take the streetcar to go to the interurban station on Third Street to take the car, destined for Delphi, that ran past Spring Vale Cemetery, for the City Street car line ended on Schuyler Avenue, short of the city limits. On the way, it was fun to see how many flags you could count. There was a walk from the cemetery gate where the interurban stopped to the family lot and then the business of clearing away the Christmas decorations, all brown and crackly; then filling the vases with water and placing the flowers by each grave.

Little Claudie died when he was only two years old, his stone said. And there were the gravestones of the other grandpa and grandma that the little boy had never known. But he was told that grandpa was an engineer, who built railroads up in Michigan and then came to Lafayette to build the bridge across the Wabash River and the railroad all the way to the Illinois State Line, and was a friend of old Colonel DeHart, who had been in the War of the Rebellion and got shot in the leg down in Tennessee and had to live outdoors as much as possible the doctor told him, even all winter, or he would lose his leg maybe, so that’s what he did and why he built Lincoln Lodge where he had his tent where he slept out all winter and then he went back to the Army, “and your grandpa knew him an’ they were friends.” And the little boy wondered how it would seem to be in the War of the Rebellion and get shot in the leg, and live outdoors all winter till you got well and then go back to the army—and the war. He didn’t seem to have anything wrong with his leg now, thought the little boy, for he had seen him come swinging out of the North door of the Court House about 4:30 in the erect way he had with the step of a thoroughbred horse. His aquiline nose and flowing white mustache and military cape thrown carelessly over his shoulders bespoke the combat soldier. To people who knew him well, although he was an excellent judge, it was never Judge DeHart, It was “Colonel DeHart.” Men almost tipped their hats to him and women followed him with their eyes.

Sometimes, it seemed to the little boy that the folks in Lafayette lived their lives, clinging to memories of the great conflict. This was evidenced by the trips of the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” troop to Lafayette, which often came aoout this time of year, usually on a Saturday. Maybe this troop operated a bit like a big circus, because you could not have a parade without reasonably good weather.

There was always a parade from the Family Theater at Sixth and Main Streets, South on Sixth Street to Columbia, to the Lincoln Club, then East on Columbia to Ninth Street and North to Main Street and then West on Main to the Theater where the matinee was scheduled for 1:30. Leading the parade was a small band playing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” while the cast trailed along in appropriate fashion. Here were the fierce blood hounds leashed, muzzled and led by an attendant, Simon Legree, the despicable one, Uncle Tom, an obviously ancient negro, hobbling along on a crooked stick for a cane, little Eva, with her long curls, and hair ribbons, obviously not over twelve years of age, and of course, Eliza.

The cast was not Broadway, but it delivered. Simon Legree wielded his black snake whip with bone chilling snaps to the cries of poor Uncle Torn, who, on his knees, would protest, “You kin kill m’ body, but you can’t kill m’ soul”. When little Eva died, really she did die. She went up to Heaven which was the appropriate reward for innocence and virtue. You could actually see her going up there, for she was literally raised beyond the sight of the audience into the Heavenly Arms above the scenery. This was by no means a matter for laughs by the audience but rather for genuine tears even by many adults. Eliza, fleeing with her first born child from the fierce blood hounds, set on her trail by the despicable Simon Legree, crossed the Ohio River before your very eyes from the Kentucky to the Indiana shore, jumping from ice cake to ice cake in the backstage of the theater while the ice cakes heaved and the blood hounds, off stage, but nevertheless, realistically, pushed a close pursuit but fortunately never caught the fugitive. This brought alive for the little boy, his Grandpa’s tales, that many a time, when he was a small boy, living in the Sixth Street house, he had seen the summer kitchen with three or four negros, getting dinner after a day in the cellar, before setting out again for Canada, following always, the North Star.

After the graves at Spring Vale had been tended it was time to catch the Lafayette bound interurban to go back to town. Then a visit must be paid as well to graves in Greenbush. Here the flags at the graves seemed more numerous. There was even a row of stones down along the North fence for the many Rebels who had been brought to Lafayette from Fort Donelson and had died at the prison where they had been confined on lower South Street. No flags were there for them—only the stones, without inscription—but aligned as on parade. There were flags on great gran4pa’s lot, for his two sons each, in his narrow grave forever laid. And there was one too, for Colonel William B. Carrol, 10th Ind. Volunteers, Tullahoma, Corinth, Mill Springs, Perrysville, Chickamauga.

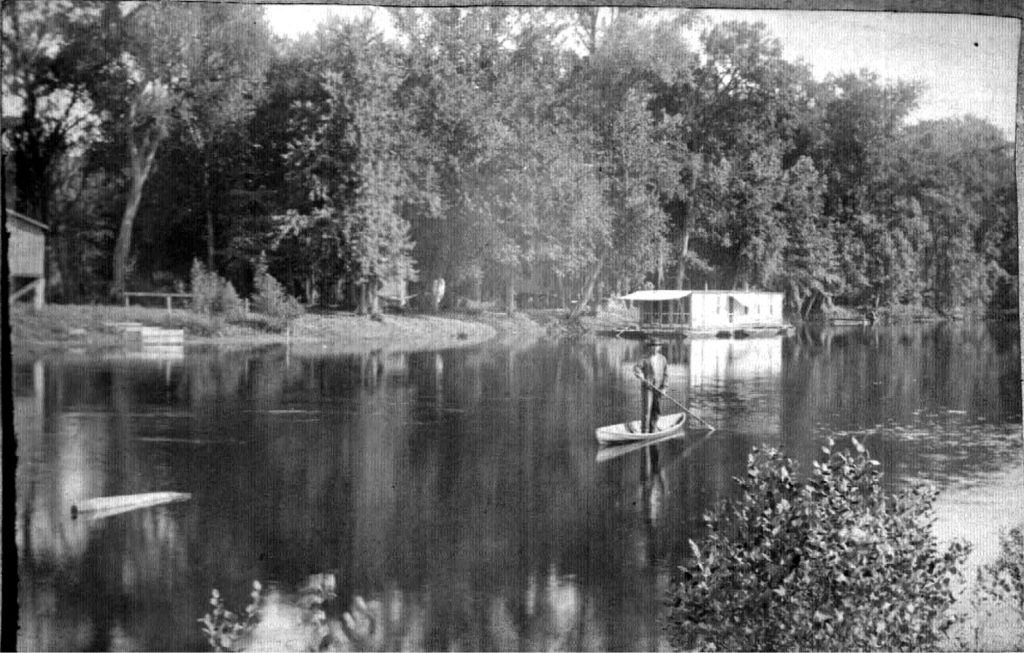

One by one the days of school dragged by but at last came the day of days that in last September had then seemed located somewhere in a vague beyond. Grandma and Grandpa were already at Riverside on the Kankakee River. Again, there was a counting of days. Finally, with the trunk all packed, the livery stable man took it by early afternoon to the Monon Station. On a Saturday, the passenger cars would be crowded with shoppers from Battle Ground, Brookston, and Chalmers. By Reynolds, it was time to get out the sandwiches and cookies from the shoe box, carried separately, entrusted to the little boy. He would have been ticking off the stations as the train passed by Battle Ground, Brookston, Chalmers, and Reynolds, and the next would be Monon, then Medaryville, Francesville, San Pierre, and then Riverside. At Monon there was a wait to transfer baggage and passengers to the Hoosier Flyer waiting on the Indianapolis to Chicago Branch, a sophisticated train with many passenger cars and a diner where despite the distance from the Michigan City train, the little boy could see the sparkling glassware, the white tablecloths, and the colored waiters, who went back and forth with large trays carried about even with their shoulder on the flat of just one hand. How exciting that world must be, thought the little boy, as he bit into his ham sandwich, now dry from his dawdd1ing and dreaming. But the Michigan City Branch would finally start with a lurch, reminding him that Grandma’s was just ahead—and the River. So sped by Medaryville with its brick kilns near the track glowing in the now deepened twilight. There would be no passengers on or off at Francesville, for it was too far from Lafayette for shoppers and the same would be true for San Pierre, called by the natives “SanPeer”. Then Mr. Pangborn, the conductor would say, at the end of the car, “Riverside, Riverside”, in that same flat monotonous tone that he used on approaching Lafayette on the return trip in September, “Lafayette, Lafayette”. How wonderful to be home again and secure in the night with Grandma. She had waited dinner and you could smell. the dampness of the river, hear and feel the ever-present mosquito. There was always time while Grandma still waited dinner, while the little boy and his mother, braving the squadrons of tiny insects, took just a short boat ride—just up to the wagon bridge and then right back. There with the soft lamp light on the dining room table, it wasn’t long until bedtime. Grandpa and Grandma lived in a houseboat, only it was up on stilts on dry land on the riverbank about five feet above the ground level, for fear of the semi-annual floods. There was an elevated walkway from the railroad embankment to the kitchen door, and a wide porch surrounded the boat on three sides. The front overlooked the river and the porch extended out over the water. There was no telephone, no radio; all lighting was by lamps and all cooking and heating was by wood for breakfast and by kerosene for dinner The wood was accumulated dead wood, from a tract of five acres Grandpa owned between the river and the railroad. Sanitary arrangements were primitive in back in the woods—by a path beset with need for a flashlight and obstructed by the attacks of the ever-prevalent mosquito. This was a character-building experience for the little boy. But nothing could equal the peace with which the little boy slept, on an upper bunk in his narrow stateroom with the gentle patter of the rain on the roof two feet above his head Lost in drowsiness, after all the excitement of the day, he went to sleep to dream about the big old bass, two pounds any way, that would be waiting for him in the morning by the birch tree that leaned from the bank just 100 feet above the house boat on this side of the river. Anyway, it was always good for a couple of sunfish, even before noon.

Riverside was a singular community even in those days. It clustered around the railroad bridge and for a small distance up and down the river, with only one or two year-round residents. Originally people from Crawfordsville had a lodge across the river by the bridge, known as the Crawfordsville House; Lew Wallace used to come there. The other houses were of people from Indianapolis who came to hunt and fish and spend the summer. But Grandpa had been there the longest. The houseboat had been built by an old river rat by the name of Captain Keys. He had constructed the houseboat one summer with three staterooms and a large forward room, heated by a wood burning stove as hopefully, that would be useful as a bar, when down the Kankakee, then the Illinois and thence to the Mississippi. Unfortunately, that Fall the boat could not be got over the natural dam at Momence and the next Spring Captain Keys was back at Riverside. Whereupon Grandpa had bought the boat. He had maintained it for many years as a houseboat until the bottom needed repair. This necessitated putting it upon stilts, where it remained until the advent of the boy.

The community had no civic life; but the; men from the cottages would at times congregate at the north end of the Monon Railroad bridge to gossip about the day’s modest events; how Dave Bomberger, for example, might have better fished the Oxbow instead of coming back with Nothin’—as he did, all this while waiting for the evening train from Lafayette—and to see if it would stop. The little boy liked to hang around these sessions where doubtless, he was not altogether appreciated, because his presence, probably restricted the conversation to what was proper for his ears.

But old Mr. Cook was a genial fellow. One night he proposed a race on the river between the little boy, his summer buddy, Glen Jackson and Mr. Cook, to be held the following morning above the railroad bridge at 10:00 o’clock sharp, rain or shine. This challenge was eagerly accepted, for everybody knew that Mr. Cook, who lived in a cottage by the bridge, had his right hand off at the wrist and always operated on the river with a paddle. This, he used by putting the stump of his severed right hand on the upper part of the paddle and pulling with his left hand. Came the day of the challenge. Glenn and the little noy, met the challenger above the railroad, bright in the blazing sun of August. But the boys had been out maneuvered in the challenge. Mr. Cook showed up, not with his paddle, but with regular oars and a double ended boat never seen by the boys before. Despite his severed right hand, Mr. Cook seemed to be able to operate the oars without difficulty. The result of the race was foredoomed by the preplanning. When Mr. Cook said “Go”, and the two boats were in mid-stream, Mr. Cook took off with a strong stroke. On the contrary, the boys were in trouble. Glenn took a ferocious swipe, to get off to a good start, caught a crab, and then missed the downstroke altogether. Tne impulse of his effort threw nim backwards, out of the boat. He emerged on the surface with straw hat, wet and streaming. He spat a long stream of Kankakee River water and grabbed the stern of the boat.

So ended the race. No comment thereon was afterward recorded by any of the participants, which signified that the boys recognized adult power on the one hand and on the other, that Mr. Cook was a gentleman.

When Glenn was back in the boat the little boy said, “Maybe we better go fishing up to the bayou”. “Yeah”, said Glenn. The way to the bayou was by boat to the wagon bridge upstream, then by the sandy road for a quarter mile to the wooden bridge that carried the sand road across a narrow part of the bayou. It was here that the water was deeper. The only trouble was that turtles were often the biggest bait stealers, as the boys let down their cane poles near the bridge pilings. And, the sunfish, flopping on the bridge, never seemed quite as large as the bobber promised, when it popped under water. Finally, the enthusiasm for bigger sunfish from the bayou would die down and the boys would head back for the river bridge, especially as the middle of the afternoon approached, as four o’ clock was swimming time at Riverside.

Everybody went in. Grandpa never stayed long, just in and out, of the water, for he said longer exposure made him feel weak. Grandma and the other ladies were clothed as upon a winter’s day. Black stockings, bloomers, a full skirt and a stiff upper garment and bathing shoes. A bathing cap topped the costume. No wonder there was little swimming by females in those days. Annette Kellennan, in the moving pictures, in a one-piece bathing suit, was an astounding, if decorous example, however of a more enlightened world.

Everybody on the houseboat side of the river tended to congregate on that side of the river at the dock. The river there had a sand bottom, and the dock provided a good place to sit with the feet in the water. For the young ones you could always use one of the gang planks as a diving board. Sometimes Herbie Green from across the river would come over. This was a big event, for Herbie was a big boy from Indianapolis. True, he didn’t have the skill. with boating, or fishing or building campfires, but Herbie could swim. When he came over, he was the best diver and could swim on his back and pull younger ones around when they held onto him by the shoulders and let their legs trail out behind. Also, Herbie had a twenty-two rifle and sometimes when he had a guest, they would go down to the Jackson cottage below the bridge and shoot at a tin can on a sandbank across the river. The little boy and Glenn Jackson always attended these shooting sessions and noted that the guest fired off a lot more shots than did Herbie. If anybody remarked on this, which really wasn’t any of their business, Herbie would put all right by remarking that, “He comes up to shoot for a week; while I come up to shoot all summer”. Such positive explanation fully established Herbie with authority just a little lower than an adult.

Sometimes during the summer, otherwise uninterrupted from dawn to dusk by continued overalls and bare feet, a circus would. come to Lafayette, maybe even Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. This was more than even the river could compete with.

The circus train pulled into Lafayette at daylight and you just had to be there to watch the unloading. First, it was the draft horses, huge and clumsy, clumping down from the cars; then the unloading of the wagons with poles and tentage, and the cook wagon to start the coffee for the roustabouts on the grounds over in the river bottoms. There was always a railroad passenger car or two that was undisturbed. That Is for the clown’s and the bareback riders, some old sophisticate would explain. Later, following the wagons, the scene at the grounds was organized chaos, while the roustabouts would gather around in a circle for driving five-foot tent stakes to put up the tentage. Armed. with sledgehammers, standing around the stake in a circle each man would take a lick at the stake, driving it down to the proper depth in less than a minute by a succession of blows that went around the circle like clockwork. How wonderful was the world of circuses.

It always had a regular menagerie, with lions, tigers, giraffes and monkeys, a raucous brass band and an adequate calliope. However, this was true of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but instead of a big top covered over with canvas, the performance was given before an audience seated in a huge semicircular tent. There Buffalo Bill (people said his real name was Cody) would ride out on a pure white. horse, with his rifle in a holster by the saddle and circle the audience, holding his western hat, high aloft to proceed and introduce a parade of all the participants, including, not only clowns, acrobats and bareback riders, but also cowboys, Indians, and Cossacks from the Far East.

Buffalo Bill’s special. performance had everybody on edge. He would ride out on his white horse, looking from side to side in case any Indians were trailing him, to the middle of the open space where there was a Spring. There he would stop to rest and for a drink of Spring water. This was done by creasing the top of his stern hat, gathering therein from the spring a hat full of water. He would let his horse have a long pull at this to the entire approval of audience; then drink himself. But just as this was finished here would come a whole posse of Indians with bad intent. These, however, Buffalo Bill finally would repel with his repeating rifle. When he ran out of rifle bullets, he had his six shooter. His faithful horse, well trained by many such incidents of the past on the western plains, would stand by motionless despite the noise. This was always explained by some knowledgeable adult as routine, because Western horses are trained to stand motionless when the reins were slack and resting on the ground, no matter what the disturbance.

Then would come a demonstration of shooting skill. Proceeded by a man on horseback with a bag full of black glass balls, Buffalo Bill would follow. As the man with the glass balls threw them into the air, one by one Bill would break each ball in the air with a single shot. This wonder would be followed by the stagecoach act where the passengers were rescued from the Indians by the cavalry. All this was so exciting that the little boy’s bag of peanuts would never be gone until the Cossacks from the Far East would follow and live a demonstration of trick riding, even standing up on their horses, bouncing from horseback to the ground and back again and accompanied all the while with much wild yelling. Nobody could tell what they were yelling because it was in a foreign language—of course. Nobody seemed to understand those foreigners. When they fell to fighting among themselves in August of 1914, it was even worse.

At Riverside the outbreak of war interested everyone. Especially this was true at the houseboat, for Grandpa and Grandma had a house guest, Miss Betty, who could talk German and had served as a governess for some time in a German family. She would relate how the King of England, Kaiser Wilhelm and the Czar of Russia were all related because of descent from Queen Victoria. Vividly she would recall the family Sunday visits to the biergarten, how sometimes a bandaged student, but in the face in a college duel, would be accompanied on a Sunday stroll in the park by his fraternity friends. Every night the Indianapolis News carried accounts of the events subsequent to Sarajevo.

There was some support among the cottagers for the Germans, for a few were second or third generation Americans. Even by the next summer any accounts of atrocities upon the Belgians were hotly disputed as just “British lies”. Gradually, with submarine sinkings and the frightful slaughter among the massed armies, the gas attacks and the shelling of civilian areas, Americans began to take sides.

Their good opinion was courted. In the winter a French military bend came to Purdue to give a concert in Eliza Fowler Hall. Never had there been a band before in Lafayette like this, not even the Purdue Band. These men were soldiers, some even had been wounded. Several had black patches over the eye. Another, a trumpeter, had only one arm. Fortunately, however, it was his right, so he could still play all right. Their uniforms were colorful with blue and red and gold braid.

Everybody, of course, stood up when the opening number was the Star Spangle Banner. The leader was a middle-aged man with a gray beard. “Zis is a song zat zee soldiers like to sing”, he would say, and the audience hung on every note. Finally, the leader, in closing, said, “An now ladies an’ gentlemen, ve vill play for you our national anthem, Zee Marseillaise. Turning to his band and lifting his baton he commanded “Allon”. The band rose as one. The audience, not to be outdone also rose clutching self-consciously overcoats and programs upon which were printed the first verse “Allens enfants de la patrie; Le jour de gloire arrivee” and below that, in case anybody could not read French, the English words. “Ye sons of France, awake to glory; hark, hark what myriads bid you rise”. The words of the last chorus, rolled over the audience like a tidal wave, “To arms, to arms ye brave”, sang the audience, now one with the band, “The avenging sword unsheathe; March on March on, all hearts resolved on victory or death ” Walking along the snowy sidewalk to the South Ninth Street car a new world was opening for the little boy. “When will America be in the war, he asked his mother?”

“He kept us out of War” said the democrat politicians all that Fall and Winter. But his parents and Grandpa always mentioned Teddy Roosevelt whenever an American vessel was lost to a submarine. There were Preparedness Day parades with bands and people marching with flags. The little boy and his mother were in one. It was at night and almost like a torch light procession, like those in which his mother and his auntie said their father used to march in for the Republicans after the war of the Rebellion. And then, as if it just sort of happened, in April it was, America at war. This seemed to change most everything.

Even Riverside was different. When swimming time come Herbie was never there. His mother said Herbie was at some place like Paris Island—in the Marines. He’d sure be a good shooter thought the little boy. Finally, Herbie came home for a vacation. His. mother called it a “furlough”. And—it was like the old days. Herbie would dive off the gang plank and pull the little kids around while swimming on his back. He was bigger and stronger and was almost black from sunburn. Finally, he had to go back to Paris Island.

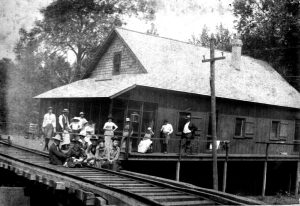

Battery C had left Lafayette for Fort Harrison-and the whole of Lafayette had turned out to see them off, together with the Purdue Cadet Corps behind the Purdue Band. But in Riverside, Herbie was the only sure enough hero to whom a farewell might be said. So, the community arranged a going away reception.

Herbie was dressed up in his dress uniform, all blue with a red stripe on each pant leg and a white top to his cap. The time was to be at three-thirty in the afternoon, so as to give plenty of time before the Monon train came by southbound at 5:00 P.M.

‘He would change cars at Monon to the Hoosier Flyer and have dinner in the splendid dining car the little boy had seen so often. And, the government would buy his dinner. At Riverside, there was plenty of ice cream and homemade lemonade. The afternoon was hot and muggy, threatening a summer storm, so that perspiration stood out around Herbie’s woolen collar that came right up to his chin, almost. The cottagers meant to be friendly but they were shy as well. Nobody knew quite what to say except. “Goodbye Herbie, take care of yourself.” Trying to be especially friendly, Mrs. Cook said , “Now Herbie, don’t you get yourself shot, or anything.” Herbie grinned nervously and said he wouldn’t. It was hard on everyone, the cottagers, Herbie and Herbie’s folks, but nobody could have said that anybody shirked his duty. Mercifully the train stopped when flagged down. Herbie got aboard with his duffle bag and pack. Then he came out on the back platform to wave goodbye as the train pulled slowly across the bridge and was on its way to “San Peer.”

The next summer Herbies’s folks didn’t come back to Riverside. The little boy never saw them or Herbie again. Often, he wondered later about the Unknown Soldier who was buried in Arlington. He never knew, of course, but anyway that grave was not like those of the Rebels along the North fence in Spring Vale Cemetery. It always had a flag and plenty of flowers on Decoration Day.

And now this story must come to an end. The traveler has been to a far-away land, no longer there. But much like Marco Polo, after his return from his years of visit to the Great Kahn in far off China, he could truly say to his friends, clustered around him, “I have not told you the half of what I have seen.”