THE ALLEN TRACE

By: Fay Folsom Nichols

Time and nature eradicate ancient trails. They live only in the memory of some old man or are fading out on the yellowing pages of a crumpled diary. Such is the Allen Trace that followed an old Potawatomi trail up from Fort Ouiatanon on the Wabash (near the site of Lafayette) to Lake Michigan. It is as nearly forgotten as those whose feet grooved the land the while they followed their natural instincts along easy grades and in comparative safety to feeding grounds, water holes, salt licks, and at last, the river and convenient fords.

It was probably this “convenient ford” that brought Trader Allen up from the lower Wabash region to make certain crossing of the Kankakee. It was the Potawatomi ford at the present site of Baums Bridge in south Porter county. The Trace was by no means a short road, nor, because of great marshy places, a straight one. Modern 43 makes a beeline from Lafayette to Michigan City: 49 parallels it for quite some distance to enter the Dunes at Waverly Beach. Each highway traverses, at times, parts of the old Allen Trace.

The Wea were still cultivating their corn fields along the Wabash when the French Traders chose Ouiatanon as their headquarters. The flags of three nations eventually waved from the top of the block house that overlooked the fields. When the Wea decided to stop an advance of the white settler across them, the great pow-wow was held at the fort. But General Scott had received his orders. In June of 1791 eight hundred cavalrymen rode into the Wabash county, and what had promised to be a large-scale feud ended. The Wea villages had been destroyed.

In less than half a century after the invasion, a young woman, Ann Ellsworth, would be forming the sentence, “What Hath God Wrought,” at her desk in her home near the site of the old fort and posting it to Samuel F. B. Morse. It was the first message over telegraph wires.

Later would be erected on the northeast corner of the courthouse lawn, one of the early works of Lorado Tafta statue of Lafayette. For many years it was generally forgotten that he had designed the statue. When the noted sculptor was reminded of the commission by a Purdue University professor, he answered: “The Lafayette (statue) was about the first order I had in Chicago as I arrived there with great hopes and little else the first day of 1886. It was a copy of Bartholdi’s ‘Lafayette’ in New York City that was required of me and one tiny photograph of that figure was all that was given me for data. I wonder at the temerity of youth, but I had to have money, and that supplies unlimited courage.”

Trader Allen would have passed the statue hat in hand. His oxen, however, have shied at the balloon which ascended at the same spot on August 17, 1859, carrying the first airmail flown in the United States-twenty-three circulars and one hundred twenty-three letters locked in a mail bag and destined for New York City. (The balloon failed to reach its destination, landing at Crawfordsville some twenty-seven miles away and completing its journey by train.)

Leaving the banks of the Wabash, Trader Allen came north, traversing the present Tippecanoe, White and jasper counties, and after crossing the Kankakee, following a sandy ridge between Crooked Creek and Sandy Hook ditches in south Porter county. It wove on by way of an old French Trading Post, Tassinong (now a ghost village north of present Kouts) and passed north of Valparaiso. From here it followed the divide between Coffee Creek and (Wum-tahgi-eck-deer-lick) Salt Creek, and crossing the Little Calumet at the Bailly Homestead, went on to Lake Michigan.

The Western Gazetteer for 1817 had said in an editorial that the Riviere du Chemin had forty miles of navigable water for a canal, and that there was in use a portage of four miles connecting it with the Little Kenomic (Calumet). This impression was a great inducement to get land communications to it, and a highway, other than the Michigan Road, soon was recognized as essential to the development of the northern part of the state. Too, Michigan City promoters were pushing the idea of a lake harbor at that location.

So even before the Indian titles to the land south of the lake were extinguished, the Indiana State Legislature had authorized the survey of a road north from Lafayette to the mouth of Trail Creek. Lismund Bayes of Lafayette was appointed as commissioner.

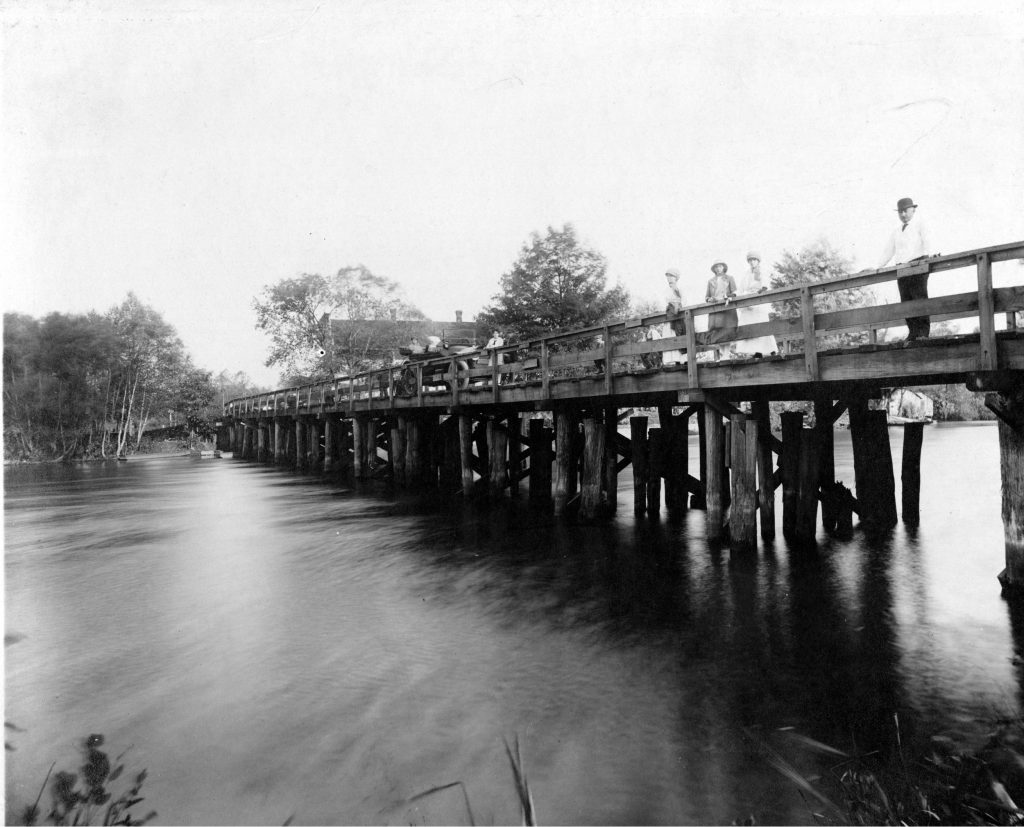

The first survey was that the road cross the Kankakee River at the lower end of English Lake, and proceed north through Tassinong. However, it was finally decided the route was too far west to be of convenience, and another $400 was appropriated to aid in a second survey. This time the road was located on the Yellow River Trail. An Indian ferry had been located across the river, and now one, John Dunn, had taken over the ferry and built a toll bridge. This followed the Andrew Burnside survey.

It was not until 1838 that a road was actually cleaned of trees and made in condition for wagon travel. Other Indian trails crossing Newton and jasper counties took the Potawatomi ford at Eton’s Ferry (Baums Bridge) and joined the Allen Trace on the north side of the river.

The Allen Trace became the old time dirt road with its wide strip of grass down the center, and its deeply-rutted wagon tracks at either side. Annually, after settlement was scattered along it, the road supervisor of each county or township, as the case might be, called upon the nearby farmers to help grade it. Then it was crowned and ditched at the sides. Three teams were commonly used to pull the huge road grader, which was operated by the supervisor himself. The sharp shovels smoothed out the ruts, and for a time the grass strip was hidden under fresh dirt. In wet weather, after the grading, let the driver beware. His spanking bays might take a sudden notion to shy, and his wagon or top buggy go sliding from crown to ditch. . In a few weeks the persistent physical features reappeared, the grass streaks and deep ruts once more predominating, and the farmer traveled it thus, until another spring rolled around.