How Firm a Foundation

Alexis Coquillard

By: Fay Folsom Nichols

On a tiny island of fragrant pine and spruce which rises sharply from the clear blue waters of the Straits of Mackinac, where Lake Michigan and Lake Huron meet, began one of the great American financial dynasties. Here, in 1808, John Jacob Astor, New York financier, incorporated the American Fur Company. After the war of 1812 he set about building up a monarchy by absorbing the Upper Peninsular’s fur industry. He became the potentate of a huge enterprise, employing a small private army to keep order. It may be hearsay that he took over the “panis,” the Canadian’s Indian slaves, but to him government agents catered to such an extent that he actually became the ruling force of the great Northwest.

Individual agents and fur buyers suffered at his hands often with their lives. Men trained the Astor way spread out over the Great Lakes’ region, and traveled the snaky waterways of the forests. It was better to be with Astor than against him.

The onion skin juice and blackberry ink have long ago faded on the crackled pages of trading post records. Too, many of the journals and ledgers have been lost to the historian, and there passed an age when memoranda were those of word-of-mouth as grandsire gave to youth fanciful tales of the daring adventurer. Movements and motives of early traders have seemed of little importance to later family members, and if diaries there were, some energetic housewife used them to start the breakfast fire.

But history has fantastic mirrors from which are reflected the mysterious past. With the French explorer came the coureur de bois (French trader gone native). Some were the reduced members of the French nobility. Others were Canadian youth who, irritated by the bonds of a strict home life, found a liking for the freedom of the forests. Of necessity they became fur traders. There was no other means of support. Those who married were like the sailor with a sweetheart in every port. They took in addition to their own wives, squaws whom they established at convenient trading posts, and whom they made no pretense of respecting. France was lenient. She had to be. These men were the links that bound New France to the mother country.

It was Astor’s men who gradually usurped the territory covered by the coureur de bois.

It was Astor’s men who kept the stone step swept clean, laid a fire in the hearth, and finally held ajar the front door of our Valley of the Kankakee-Alexis Coquillard, Joseph Bailly, Joseph Bertrant, Pierre F. Navarre and Comparet. To Noel le Vasseur and Gurdon S. Hubbard are accorded the honors of opening the back door. The draft thus created followed up our river.

In 1825 the Erie Canal opened up to the West, making possible an easier route for the transportation of the riches of the Northwest to New York markets. This same year the American Fur Company appointed three agents for the Northern Indiana territory. Two were destined to play important parts in the development of the Valley, Navarre and Coquillard, acting as liaison officers between the company and minor agents in the early decades of its history. Both men eventually settled in the Valley of the St. Joseph and became inextricably linked with the Valley of the Kankakee.

Navarre came and built his log cabin and trading post on the banks of the beautiful St. Joseph River. The site of his home is said to have been one of exceptional beauty, and historians who have written accounts of this region are unstinting in their praise of Navarre’s choice. They describe it as having been covered with a magnificent growth of oak, each tree growing far enough apart from the other to permit a wagon to pass and cleared of underbrush by annual Indian fires. Overhead the graceful branches of these magnificent trees formed an uncomparable canopy. Like many another French trader, he married an Indian girl, remained faithful to her and reared a family.

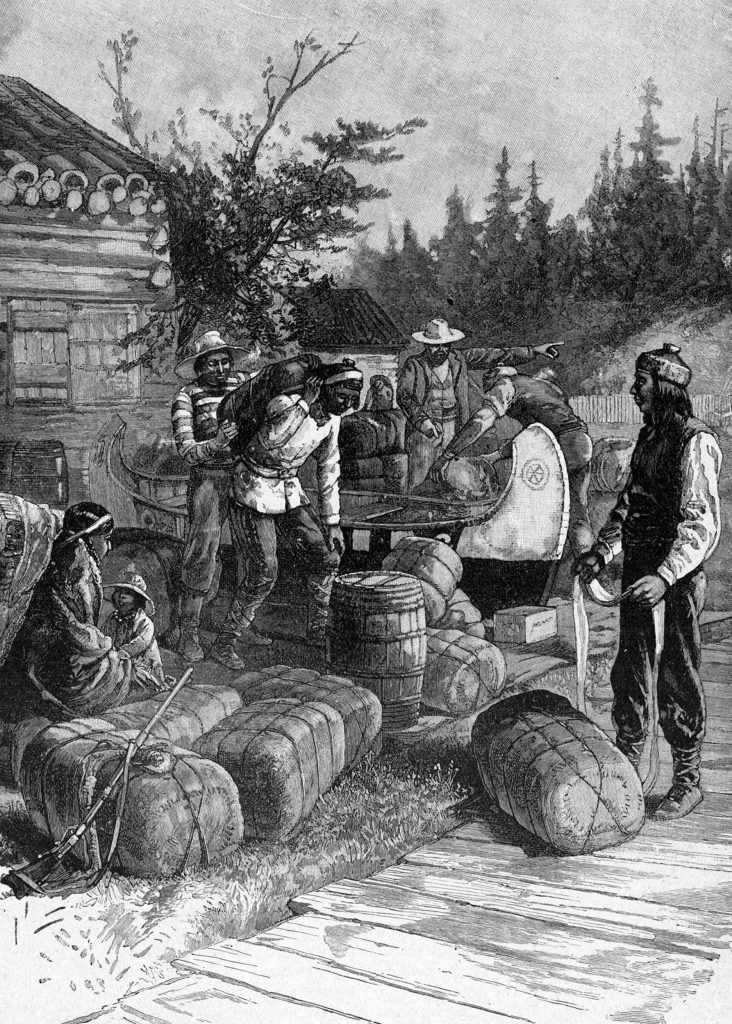

The Potawatomi from the Kankakee region found Navarre’s a convenient and profitable trading post. Twice a year they came up the river, their canoes loaded with prime pelts, maple sugar, baskets and other articles, to trek across the portage path and trade with the Frenchman for whiskey, trinkets and money. In the spring Navarre and his men made the pilgrimage to Mackinac, the “entrepot” of the huge fur industry.

When Alexis Coquillard took up his duties with the American Fur Company at Fort Wayne he was twenty-five years old. The year was 1820. He was of the sixth generation of his family in this country, being descended from Peter Serat dit Coquillard, a mason who came to LaChine, Canada, from France and there married, in 1687, Frances Sabourin.

Historians depict Coquillard as a large man with light hair and blue eyes. Some claim he was neither able to read nor write. The collection of Ewing letters prove them mistaken. In these letters we see a determined, resourceful man of business, far seeing and successful.

So sure was he of his own success, so confident in his own ability, that he persuaded his partner at Fort Wayne, Comparet, to stake $75,000 in the purchase of the extensive agency of the American Fur Company for the region of the upper Great Lakes. He had spent quite some time familiarizing himself with the country and its resources and had acquired confidence in its future.

As his wealth grew, Coquillard felt he should take a place in the life of the community comparable to his means. Thus he erected an outstanding brick dwelling, fine and dignified, on the top of a hill overlooking the city.

Spacious rooms, open one into the other, with a ballroom on the third floor spoke of warm hospitality. Here he was to bring his bride, the lovely Frances Comparet.

Some historians speak of her as the daughter of his partner, but all picture her as small, with the usual dark colorings of the French, vivacious, well educated and able to take her rightful place beside the enterprising Coquillard.

They were married in 1824, but it is thought by many that the bride never occupied the lovely home at Fort Wayne. At this time the young husband, following the purchase of the Upper Lakes agency, came to manage the territory about the present city of South Bend. Thus the young couple were to make the first civilized home in the wilderness where now prospers a magnificent city.

Perfect in their devotions to one another, they were united in their aspirations, alike in their ideals. Near his trading post Coquillard constructed a commodious log residence and with his courageous young wife, brought to Northwest Indiana civilized customs. Here in 1836 was born their only child, a son whom they named Thomas. Their nearest white neighbors, beside Navarre, were at Bertrand and Gary’s Mission at Niles. Because of a sympathetic, understanding nature, Frances Coquillard became a strong aid to her husband in his dealings with the Indians.

Coquillard is credited with having a thorough knowledge -of the Indian’s character, understanding several languages. They had confidence in his honor and good faith, and he became the intermediary between the Indians and the government, serving both loyally and well. He acted promptly in conducting the treaties of Tippecanoe, Fort Dearborn, and other places subsequent to the peace of 1814, and was always in high favor with Governor Cass, Commissioner Isaac McCoy and George Crawford, secretary of the Indian Agency.

The trader must have worked down the Kankakee, for in October of 1832 we find he purchased from Chief Topenebe one section of land that had been given that Indian by the government Treaty of Tippecanoe, paying him $801.85 for the float. Located in the present Benton county, he later sold the section for $1,200 to Edward C. Sumner, a Vermonter who came to the Parish Grove locality in 1834.

When Coquillard felt the fur industry was waning, he took particular interest in the development of South Bend. He had a reputation for doing things on a large scale, but not always did he hold the trump card. At one time he sought to divert the waters of the Kankakee into the St. oseph, endeavoring to produce unlimited water power for a mill site-a mill that would compete with any mill west of Rochester, New York. After the work was begun it was found that the location of this lake was a water-shed and the water leaked away in the loose soil so rapidly that only a small amount ever carried on to South Bend. He had mortgaged land holdings to the State Bank to finance the venture, and the bank was obliged to foreclose.

When it was finally decided to remove the remaining Potawatomi from this region to Kansas, Coquillard was the man selected by the government to accomplish the tremendous task. In this he had a partner, a man named Alverson. They were to be paid $40,000 by the government when they had accomplished the removal.

Coquillard had been a friend to the Indians. His letters in the Ewing collection state his concern both for their physical and spiritual well being.

“You seem to think,” he wrote Ewing, when negotiations were underway, “that there would be a great saving to move the Indians by water, but I don’t think there will be much difference in the cost either way. We will have to take teams to get them together for shipment and again to take them west from St. Joseph. But you can calculate these things as well as I can. You know boats do not agree with the Indians and we will likely lose a great many of them that way.

“Should the department postpone payment until we get there we could sell the teams we would have at cost and move, often having saved $50 to $75 by the use of each team.” This letter would indicate Coquillard’s knowledge of the slowness of the government to act on internal affairs.

The letter continues, “The clothing ought to be taken out of the National amount and not from these Indians alone. It was done so before. I hope you will have this petition’ attended to by the time the roads get so I can travel and then I will go to Wisconsin and see what can be done. They will ask for clothing and I can’t promise it until I know it will. be given and we must have it and they will also want to. know about the payment. You know the Indian Character` and that they expect and must be given all that is promised them. Signed: A. Coquillard.”

In another letter to the Hon. Luke Lea, Comm. of Indian Affairs, he respectfully requests “that the Rev. Father Koken be detailed for the purpose of accompanying the emigration. He is a resident missionary of the Potawatomi on the Kansas River with the Nation. He is an excellent man, has long resided among them, speaks their language, understands their habits and wants, is a good physician, in every respect the right kind of man to accompany them.

“I also desire to state these Indians are very poor and destitute of clothing. Desire money advanced . . . $15 or $20 per head … indispensably necessary.”

History says Alverson pocketed the $40,000 and that this defalcation of his partner weighed heavily on the spirits of Coquillard for a time, but the same energies that made his fortune restored it.

During these years Coquillard built three mills-one sawmill and two flour mills at South Bend. The Kankakee Custom Mills which he built in 1837 were located at the outlet of the canal he dug from the Kankakee to the St. Joseph, near the foot of Marion Street.

After a dam was built on the river in 1844, he built a more modern flour mill on the northeast corner of the present Colfax avenue. Here, in January of 1855, he met an untimely death. A fire swept through the mill, and the next day as Coquillard was inspecting the building to make an estimate of the damage, he fell from a beam, the fall resulting in his death.

The Hon. Schuyler Colfax, editor of the South Bend Register, and afterward a vice president of the United States, gave the entire front page of the March 1, 1855, issue to a eulogy for “The Venerable Alexis Coquillard.”

A simple stone, in the north wall of the chapel at Cedar Grove cemetery, Notre Dame, bears the inscription: “Alexis Coquillard. Died, January 8th, 1855, age 59 years, 3 mo. 10 days.” This in memory of a great traveler upon a great thoroughfare.