Jasper County

By: Fay Folsom-Nichols

The fires still glowed in the camps of the Redmen that fringed the streams and groves south of the Kankakee when Austin W. Morris, United States district surveyor, pushed his ox team along winding rutted paths up from the Wabash country to spend long days dragging his surveyor’s chain through the tall marsh grasses, marking his way, the while, with chops on the hardwood; to endure lonely nights in his covered wagon poring over endless figures or noting on his map salt licks, salt springs, all water courses and mill sites.

The thick undergrowth of alternate swamp lands, sterile sand ridges and wet prairies impeded his progress. Greenhead flies, swarming by the thousands and stinging unmercifully added to the discomforts and difficulties of his task. The ague-breeding bottom lands mocked his every step. His skin became tough from harsh winds and yellow from repeated attacks of malaria and large doses of quinine. Yet he had nothing but praise for the territory in which he had worked. He visioned beautiful farms once the settler came.

But in that same year, upon the head of President Jackson, along with his troubles with South Carolina over a protective tariff, and his worries because of the nation’s banking difficulties, were piling the severe criticism of his countrymen as they accused him of “wasting the government’s money having these worthless lands surveyed.”

The people of Indiana, themselves, were urging Governor Noah Noble to continue on with the internal improvements already begun in the settled portions of the state, rather than spend the state’s money in a territory still inhabitated by the savages.

“Go on with the Michigan road”; they urged, “extend the Wabash and Erie canal to Terre Haute; dig a canal through the Whitewater Valley,” and so on until it seemed it might be a long time before the rich prairie lands of the Kankakee Valley would have many settlers.

Since 1831 when Joseph Bruel, an enterprising Kentucky showman, had gone about the country exhibiting a miniature locomotive, it looked as though the Indiana legislators might have to spend a little money building railroads if they were to satisfy a demanding public. Bruel moved his little engine from place to place in a Conestoga wagon, together with a diminutive passenger car and a few rods of portable track. When he reached a town of consequence he hired a man to help him take the railroad out of the wagon, and then he’d set it up and persons having the price of a ride would experience the thrill of being transported a short distance by steam.

Some of the people coming up to settle south of the River had seen Bruel’s little railroad. They had great hopes some day a railroad might penetrate this region in which they chose to settle. As early as 1829, The Potawatomi and Miami Times, a Logansport weekly, in its issue of October 10, said, “The backwoods may well be said to be receding. Over 3,000,000 acres in the Northeastern part of Indiana just beginning to get settled. Folks just beginning to come in good now. Grow corn high’s a man’s head. I’ve seen it.” The same lush prairies waited the plow in the Valley.

The annals of the pioneer south of the Kankakee began to be written. After the treaty of 1832, jasper county was opened, and the first white settler, William Donahue (or Donahoo) drawn, perhaps, by its wild game and fur trading possibilities, rather than farming industry with no market for one’s hard earned produce in so new a country, was staking out a claim in the present Gilman township.

Soon prairie schooners by the hundred were on the Vincennes Road, bringing the best blood up from Kentucky, Virginia and southern Indiana; cattle, horses, children, to plant their feet in a new country.

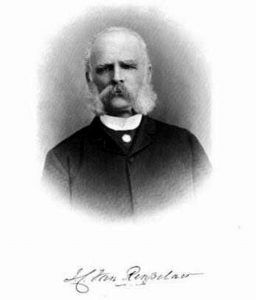

James Van Rensselaer, a merchant of Utica, New York, and his son, John, inspired by the fantastic tales of land agents as to the possibilities that awaited the settler in Indiana Territory, set out from their home in the fall of 1835, with the purpose of investing money-possibly laying out a town -at some desirable spot in the territory.

As they went south from Logansport they found themselves traveling through an enchanted realm. A country with a future in which they wished to have a part. They returned to their eastern home, but May of 1836 found the two men setting out on their planned venture. This time they probably came out on the National Road and the Ohio River, for family letters reveal they entered the state at Evansville.

Coming north to Lafayette, young John left his father there while he journeyed by horseback with a land owner, Benjamin Reynolds, to his home near the present town of Monticello. Here he purchased land, but hearing of the Falls of the Rockwise on the Iroquois, his curiosity was aroused and he determined to visit them.

In his memoirs John Van Rensselaer wrote: “Saddling my Indian pony, I found my way to William Donahue’s, a trapper. For a consideration, he consented to guide me to the Falls, lying west of him, and in a region still occupied by many of the Potawatomi Indians. Though surveyed, it had not been marked. With a full supply of jerked venison and Donahue’s bread in our saddle bags, Donahue and I started off in the morning of a beautiful June day.

“The country showed itself a marvel of beauty. Words cannot describe it,” the adventurer recounts.

All about him were magnificent oaks, clear of all underbrush. He rode through the oaks to the prairie north and back to the river. Not a house was there; not a white person did they meet. Instantly the thought possessed him-here would they establish a town. They rode about trying to locate the surveyor’s stakes, in search of township and section numbers. None were to be found.

John returned at once to his father at LaFayette. Together they reported to the land office at LaPorte. They purchased two floats. However, one of the three eighty-acre purchases, including the Falls, had been located by other parties, who were there with their friends to watch the proceedings. The maps produced, the purchasers marked the singular conformation of the river at the rapids, traced thereon, and were lucky enough in their choice of the lower and upper eighties. The owner of the other eighty capitulated, and the Van Rensselaers bought their land for $2,000 cash.

By June James Van Rensselaer held the rightful title to the Rapids of the Iroquois. Here he built a dam and with the water power operated a sawmill, and later a grist mill. And a town was born.

By 1840 by an act of the Indiana legislature, the village site became officially Rensselaer, and the county seat of Jasper county. Van Rensselaer, himself, at his own expense, erected the first courthouse in 1845.

Today, Indiana State Highway 53 runs the length of Rensselaer’s main street, Washington street, and curves gently southwest, following an old Potawatomi trail. A picturesque concrete bridge spans the Iroquois at the “Rapids.” Silver arms glisten in the early morning light; the noon day sun travels up the river to pause above it, and the red and gold shafts of twilight strike it through lovely St. Joseph college campus.