In 1919 Jim Collier returned to his family home and store at Baum’s Bridge in south Porter County, Indiana. It was decided that the original wood foundations of the Collier Lodge needed to be upgraded to a cinderblock base. While digging the foundations for the base a skeleton was discovered. A friend of Jim’s was knowledgeable about Indian relics, so Jim called Carl Black to look at the find. Soon after, an article appeared in the Valparaiso Vidette-Messenger about the discovery. Black later acquired Jim’s collection and in 1960 articles were printed in the Gary Post-Tribune and the Vidette-Messenger. Below you will find the articles, plus some pictures that ran with the stories.

Dr. Mark Schurr, professor at Notre Dame University, began archaeological digs at the Collier Lodge site in 2003. On March 8, 2018 Dr. Schurr will be doing a program about his discoveries for the Porter County Soil and Water Conservations District’s annual meeting. The program is open to the public. More information can be found included on the article webpage.

Collier Lodge Skeleton Mystery

Skeleton of Indian girl is found near Valparaiso

Vidette-Messenger

November 15, 1919

Carl Black, residing three miles east pf town has a brand-new skeleton in his home—new as an arrival, but very old in point of years. From the Kankakee River he brought the skeleton after James Collier, Baum’s Bridge merchant, had unearthed it under his store while excavation for a basement.

Mr. Black received a telephone call from Mr. Collier regarding the discovery, and the Valparaiso relic hunter wen to receive the skeleton as gift. Some of the bones had been broken by the spade use digging, but they can be put together and the skeleton will be nicely rebuilt.

The bones are those of an Indian girl, Mr. Black explained Saturday night, for scattered through the earth where the skeleton was found were many little white shell beads. These had been placed around the neck before burial. Also, there were no weapons or pipes buried there. This indicated that they were the remains of a girl or woman. Mr. Black can tell by the color shading of the bones he states, that they were not those of a white person.

The Indian beads are regarded as fine relics. They are now cleansed of the earth, strung on a thread, and are quite ornamental. A magnifying glass shows very fine workmanship of them.

The skeleton was fond on the site of what may be an Indian burying ground. Three other skeletons have been found there, according to those who live in the river country. The bones are still quite firm; so are the teeth that dropped from the jaw bones. The incisors are small, round and sharp, almost like those of a dog. The molars are very similar in shape and size to the teeth of the Caucasians.

Carl Black has a wonderful collection of Indiana relics, and some day he expects to have them arranged in glass cases so that the public may get some idea of them. Included are hundreds of arrowheads and tomahawks, and he has Indian pipes of various tribes. Only one of these pipes was found in Porter County. Like Indian beads they are hard to find. The beads from the skeleton are the fines Mr. Black has ever seen. Some have even ventured to call them pearls that were gathered from clams in the long ago in the river that is now turned into the Marble ditch. Mr. Black will return to the Collier place and see to many remaining beads and other relics that may be still resting beneath the Collier store.

Pottawatomie Projectiles on Parade

The Gary Post-Tribune

Sunday, January 29, 1961

The Pottawatomies wouldn’t recognize their arrowheads and spear points—all artistically mounted on display boards and neatly stored in the spacious basement of a brand new suburban Gary home.

But one of the biggest collections of artifacts of the primitive people who roamed this part of the country long ago is to be found in such a setting—the home of Carl R. Black at 5601 Adams St.

Black, now 78, spent about 50 years of his life getting together this fabulous collection. He found some of the items just lying on the grounds excavated mounds in Indiana for some others and bought many items from other area collectors.

He doesn’t know how big his collections is, except that it numbers in the thousands.

His most prized possession is a collection of hundreds of tiny mother-of-pearl beads made from clean shells. Black painstakingly sifted them from earth surrounding a skeleton he found in a Northwest Indiana mound.

These aren’t traders’ beads,” he says. “I took them to a museum in Chicago and had them checked by experts.”

The beads are tiny—little larger than pellets for an air rifle. How the primitive People managed to drill a tiny hole through each one is a mystery.

Just as big a mystery, however, is how ancient man made his arrow and spear points.

“It’s a lost art,” Black says sadly. “All we know about the process is that it involved chipping and the use of pressure and hot water.

“There are a lot of people faking arrowheads today, but the fakes are easy to detect. It’s very difficult to duplicate the crude work of ancient man.”

Black’s collection of Indian relics points to the fact that Indians and the early ancestors of modern man used whatever materials were at hand. Most of the arrowheads are made of flint chert, which is common in glacial deposits in this area. Most of the ax and tomahawk heads are made from granite boulders which also are plentiful here.

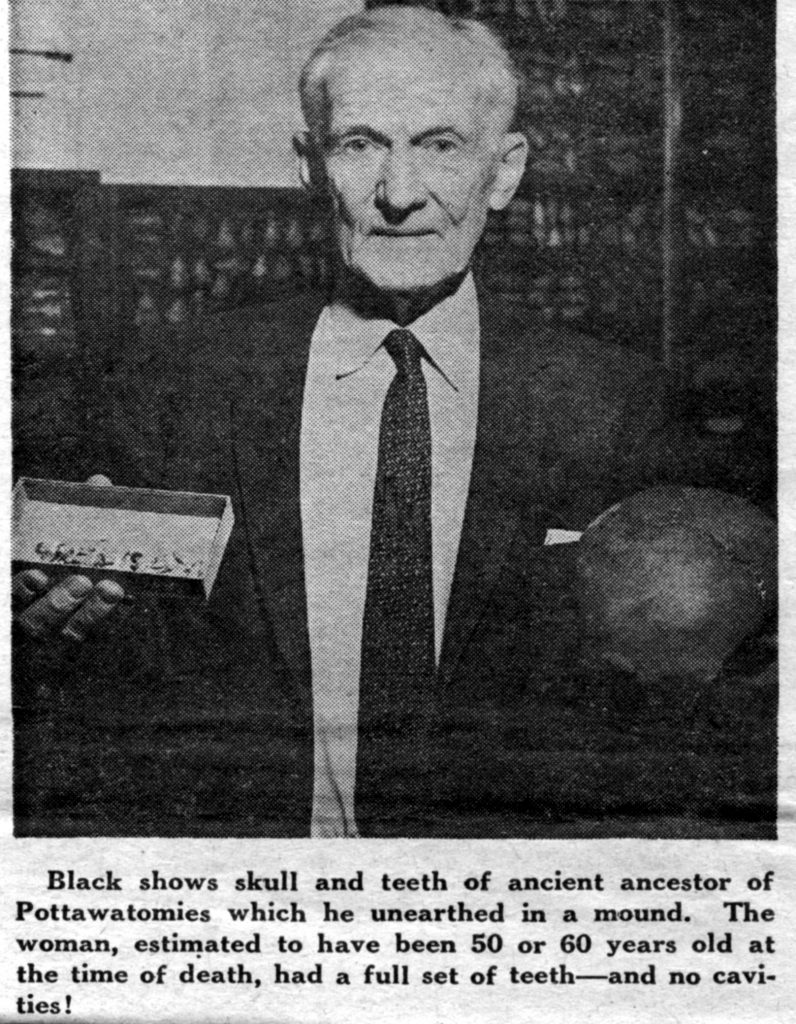

Another of Black’s prized specimens is a skull which he unearthed in an area mound.

The skull has been identified by experts as that of a woman, 50 or 60 years old. Found with the skull was a full set of teeth which had fallen from the jawbone.

“I loaned the teeth to a dentist who mounted them on a wax and took them to a dentists’ convention,” he said.

“They caused quite a stir. Here was evidence of a middle-aged woman whose teeth had been worn nearly flat—almost down to the gum line—and there wasn’t a sign of a cavity.

“And they hadn’t heard of toothbrushes in those days,” he chuckled.

Black can’t remember just when the arrowheads collection bug hit him, but he recalls that as a youngster in Valparaiso (where he was born and attended school and college) he used to find arrowheads in his strolls around the countryside.

“I bought most of the items in the collection” he says. “One man couldn’t find a collection like this in a lifetime. And now they’re even harder to find than when I was a kid.”

Black, however, did his share of prospecting for artifices. He has excavated mounds in southern Porter County and in Jasper County.

“I used to dig in mounds during vacations, and sometimes I just took off from work for a month or two at a time to excavate.”

He recalls one time when his shovel stuck a hard object in the middle of a mound.

“I kept digging very carefully, then came to charcoal—evidence of an ancient campfire. Now I was sure that I was going to find something important.”

“And you know, I sifted that site and the only thing I found was one stone implement. It was a good specimen, but that’s all that was in that mound.”

He hopes one day that he can sell his collection so that more people can enjoy it. There just isn’t room in his home to spread the collection out so that the people can see it.

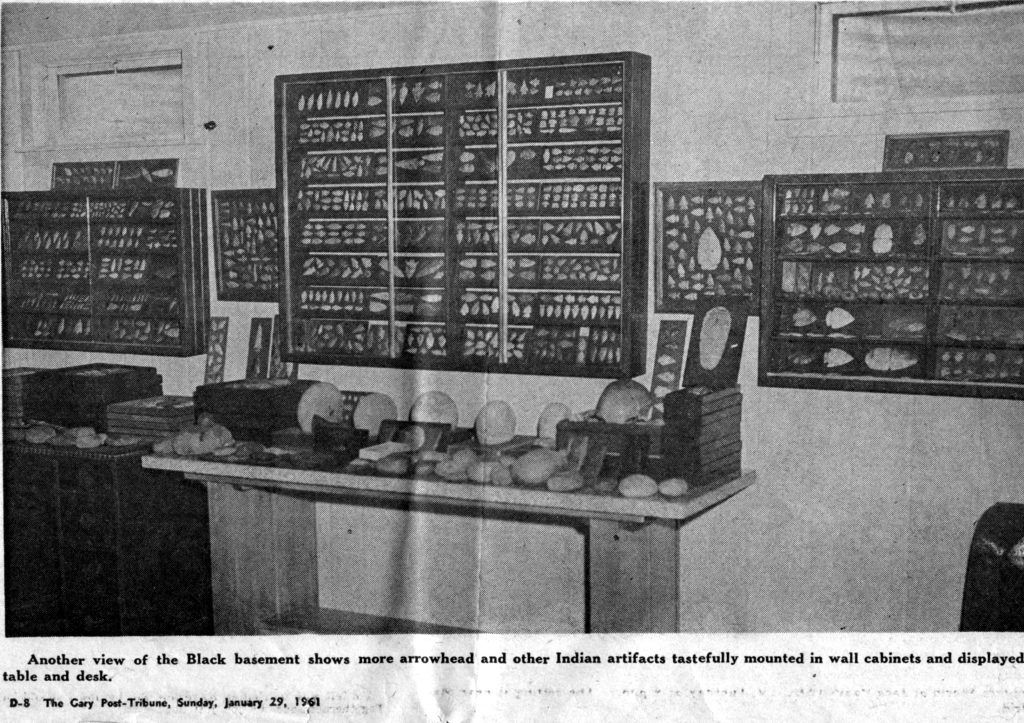

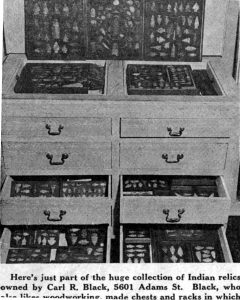

Black has other hobbies, including gardening and woodworking. The latter talent he has put to good use, by building cases for displaying and storing his prized Indian relics.

Now retired, Black had a long career as auditor and bookkeeper for various Chicago and Western newspapers. He also was in the food supplying business in Gary for several years, and for a time was auditor of the Gary County Club.

Indian Collection Boasts Expensive Pearl Necklace

Vidette-Messenger

November 18, 1960

When the Collier Hotel was built a half century ago at the ancient Indian Ford, there was disinterred the body of a wealthy Indian woman wearing a mother-of- pearl necklace and some other elaborate ornaments.

Carl Black has that necklace now in his famed Indian collection. He also has the woman’s skull, and teeth and some of the better-preserved bones, for which scientists have deduced that the woman was probably of the early Algonquin tribe that once occupied the village at the ford.

The fact that her garments were of the finer workmanship—garments of which only shreds of material remained—that she had been buried with her necklace and ornaments, and that she had been buried away from the common burial place, indicates that she was woman of great prominence, probably a Chief’s wife.

This burial was before the age of metals among the Indians. All of the ornaments were of the stone age and the 360 beads in the necklace showed that they had been drilled with a bow drill and an antler splinter.

There are 8,000 items in the Carl Black collection, wonderfully displayed at his Merrillville home, but none seem as informative as does this necklace.

It has been known for 125 years that the ancient Indian Ford was once the site of a populous village. Deer antlers in great quantity have been dug from the swamps. During the days of the drainage project great tangled masses of these horns were excavated, and their condition indicates that the oldest of them were discarded into the “bottomless swamp” about 400 years ago.

The deterioration of deer antlers is decidedly a measurable process. The antlers dug from the greatest depth were the finds most interesting to the scientists.

Near this one-time village was also an Indian cemetery. Disturbed by the steam shovels, the skeletons were simply dumped into the banks and covered as the ditching progressed. But this burial of an Indian woman was distinctive, and the workmen, knowing Carl Black’s interest in Indian relies, moved temporarily to a new location while he was sent for.

As soon as he arrived he began slowly and methodically screening the dirt to recover the pearls After many hours work the collection consisted of 360 beads.

The whole situation was startling, for only the most wealthy could afford these rounded mother-of-pearl beads, matched as to size and color, and drilled with great precision.

These beads were made from the detached knobs of the inner hinges of river clams and were once beautifully lustrous, but now they have assumed an Ivory cast because of their long deposit in the iron-bearing earth.

The search continued for five more pearls, for there was a supposition that the Indians of that period knew that there were 365 days in a year. But that was problematical. In any event only 360 were found.

Today the string contains only 359, for Mr. Black took them to the lapidary department at Marshall Fields, and the expert in charge asked permission to crush one bead to examine its inner structure.

When these beads were discovered Mr. Black took them to Mrs. Dell Beach, who restrung them in their properly graduated order. They range in size from 7 to 11/64 of an inch.

With this display of beads In the Black collection there is included the well-shaped skull, the jaw bones and the teeth. Dental authorities have said that the woman was probably 50 years old when she died, that the teeth were excellent, without a sign of a cavity, and that the head and jaws showed no sign of a wound or break.

The rest of the skeleton, except a few of the larger bones, was in such a condition that the bones crumbled to dust upon exposure to the air.

It was probably 290 years ago that Marquette came to preach to the Indians at the Lake Michigan shore line villages; during his period of practice preaching, before the Joliet journey.

Since there is always a possible error of a 100 years or so in most of these appraisements of time, there is the possibility that this woman whose body was disinterred 50 years ago, lived when “The Beloved Black Robe” came from Mackinaw to bring Christianity to the Indians.

There was never a title among the Indians of King or Queen. However, this woman of the Pearls may have been of queenly proportions and possessed queenly jewels. Probably she was a Chief’s wife.

In Black’s collection are hundreds of rare stone age items, and his collection of arrow heads is hardly equaled by any other in Indiana. The offers he has had for the entire collection seem staggering—but to all Mr. Black is utterly indifferent.

With his ability as a craftsman he has built many cases and wall cabinets, miniature caskets and display panels. The collection, occupying most of the well-finished and commodious basement in his home, is so intelligently displayed that a visitor is never aware of the chill and desolation of the ordinary museum. Here is a collection worthy of loving care and it has had that.

Strange as it may seem, there were once lions and tigers in Porter County. They were here shortly after the melting of the glaciers and were apparently contemporary with the Mammoth and the Mastodon.

The tiger was a saber-toothed animal, and the lion was the long-bodied wildcat, the male of the species had a mane, and both male and female had broad claws.

Bones of these have been unearthed by earth-moving machines, and some of them, with many other items of Porter County occupy prominent places in the Black collection.

The find by Ira Connell and John Bissel at Indian Island many years ago of a skeleton of a strange animal “with a large head and a very long body, with forelegs short and hind legs long—something like a kangaroo has been lost in the disposition of barrios estates, but should it still be in existence,.” Mr. Black wants to buy it for his collection.

But no matter what he eventually adds to it, there is nothing more interesting than the beaded necklace once worn by an Indian woman of great prominence at the Indiana Ford across the Kankakee in the south end of Porter County.